Summer 1970 and I have a new chum, Ronnie Temple who I remember fondly for three things; his mum was gorgeous, she wore tiny miniskirts and had Dusty Springfield hair; he had a great combat jacket, like something Soviet Special Forces would wear, and most importantly for this review, he have me gave his collection of 1969 and 1970 ‘Cycling Weekly.’

I read every one of those magazines from cover to cover; touring articles and all.

They gave me my first understanding of our marvellous sport; the Classics, the Grand Tours and the stars.

The men whose pictures I poured over are still among my heroes; Merckx, Sercu, Ritter, Porter, Gimondi, De Vlaeminck…

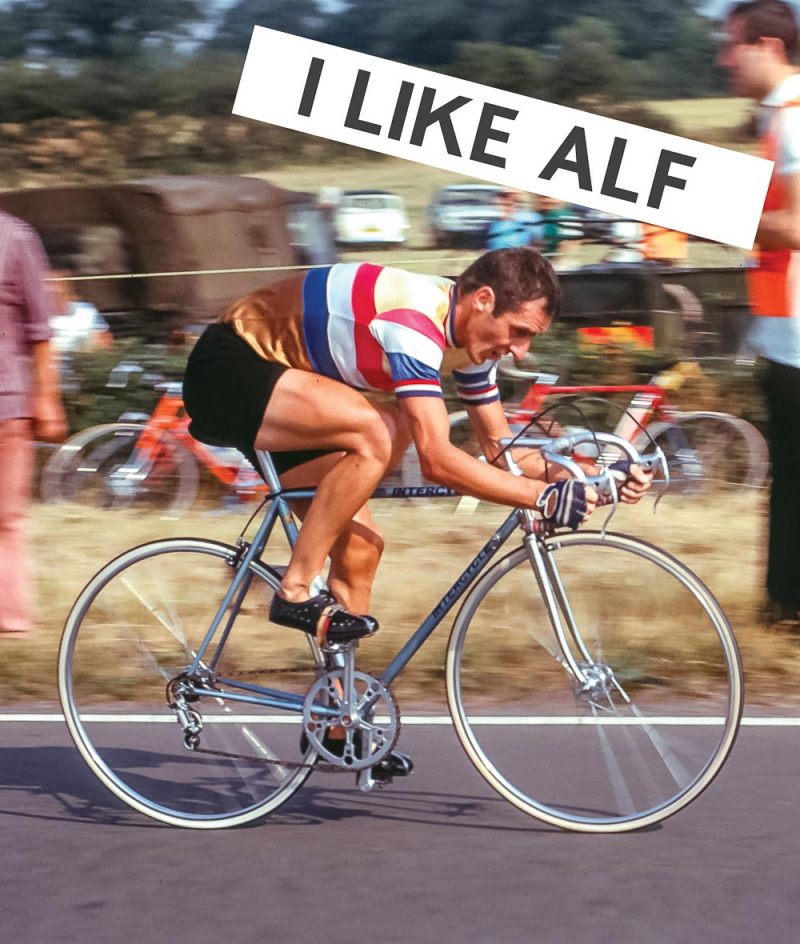

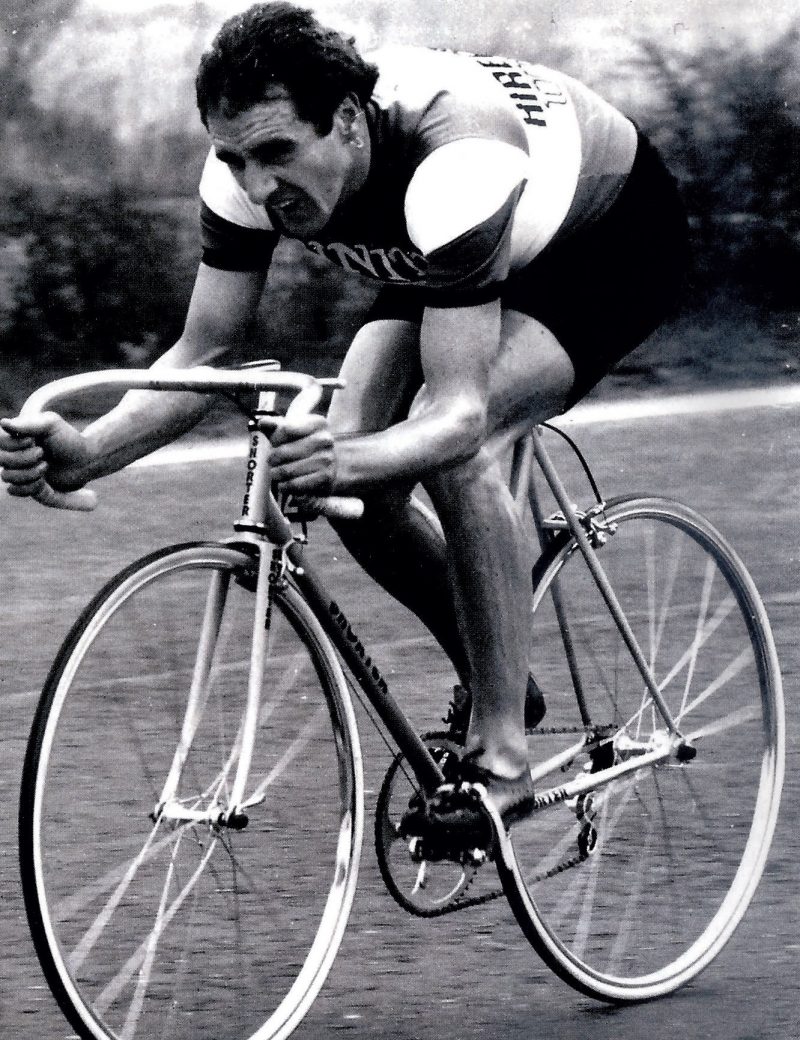

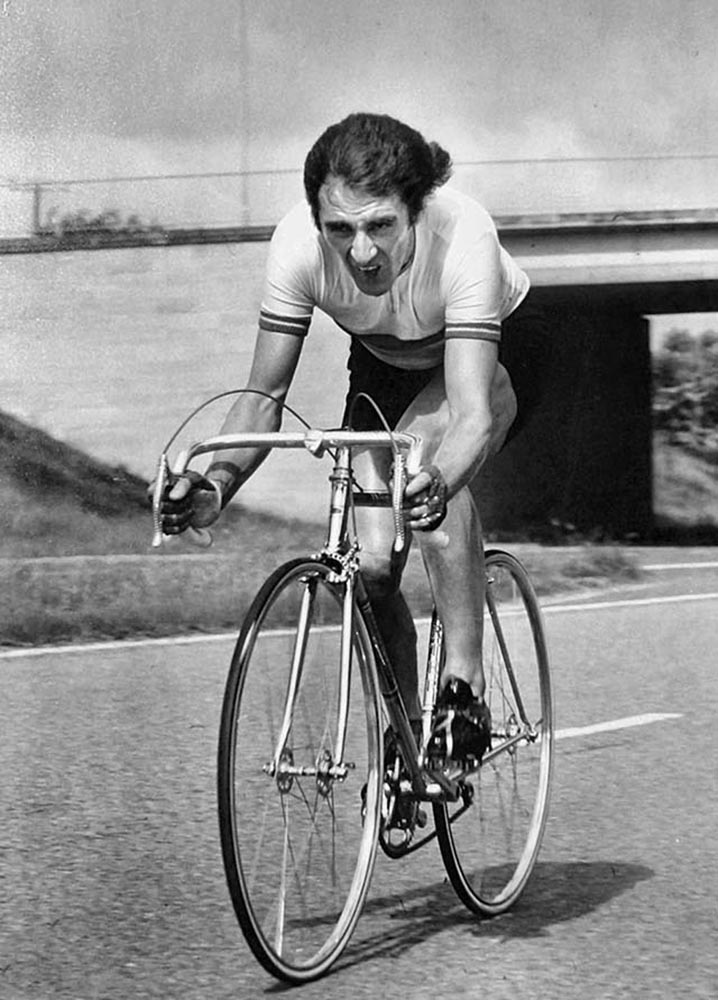

But the man whose image fascinated me and who I would come to idolise wasn’t a star of the Euro stage, his habitats were the fast rolling dual carriageways of Yorkshire and Essex – the “dragstrips” – in England, Alfred R. Engers was his name; “Alf.”

His bikes were the coolest, his position perfect, he owned the 25 mile time trial record, breaking it twice in 1969 with 51:59 and 51:00, some 10 years after he’d first broken it with 55:11.

He was and always will be, ‘The King.’

* * *

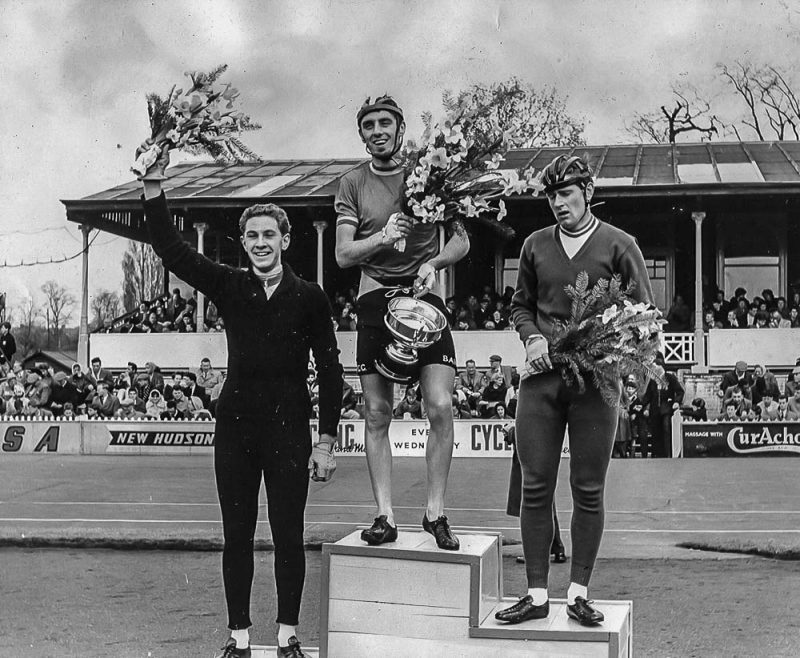

Paul Jones had the rather splendid idea of writing a book about the man who was British Junior Road Race Champion, British Kilometre Champion, twice British Team Pursuit Champion, six times British 25 Mile Time Trial Champion and who unearthed the Holy Grail of time testing – the 30 miles per hour 25 mile time trial ride; stopping the clock in 49 minutes and 24 seconds in August 1978 on the E72 course in Essex.

Sub-50 minute rides are commonplace now with the record standing at a mind boggling 42 minutes and 58 seconds to former Polish Elite Time Trial Champion and Giro rider, Marcin Bialoblocki; but Alf was the first to achieve this historic feat.

I was a little panicky to start with as Mr. Jones had me reaching for my dictionary but my limited Fife vocabulary was un-stretched once the narrative began to deal with Alf’s long, brilliant but undoubtedly controversial reign.

As a disciple and interviewer of Alf I knew about much of what the great man had to say but there were tales in there that were fresh to me.

I wasn’t aware that he’d started off as a cycle speedway rider on post-war London bomb sites, for instance.

And whilst I knew he’d ridden as an ‘independent’ – a ‘halfway house’ between amateur and professional – I wasn’t aware he’d plied his trade in the kermises of Flanders, if only briefly.

The deal with the independents was supposed to be that if they decided the pro peloton wasn’t for them, they could simply revert to riding as an amateur.

In reality it took Alf – I can’t say ‘Engers,’ that would be disrespectful – five years and five attempts to get reinstated.

Those five years were in his mid-twenties, we can only guess how good he could have been had his career been allowed to develop through that period.

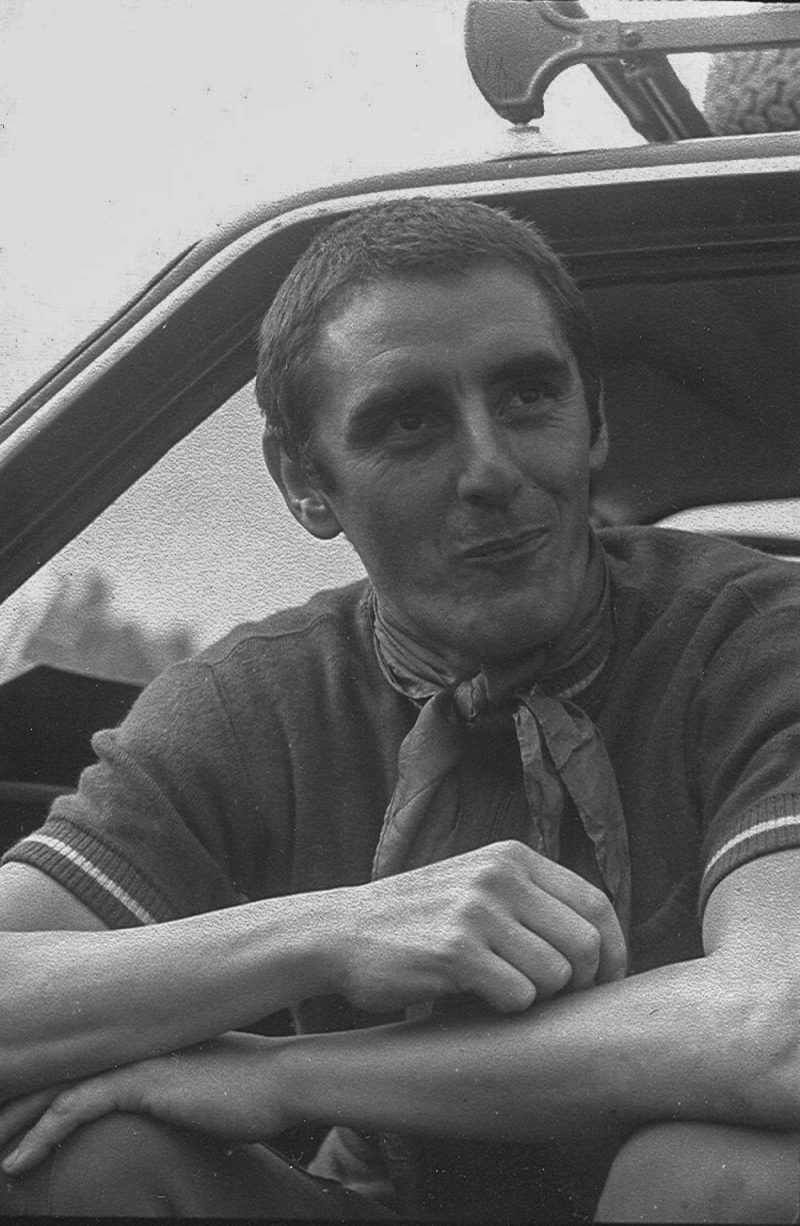

Alf’s flamboyance never sat well with the ‘grey men’ and ‘blazer wearers’ in cycling’s ‘corridors of power.’

Time trials on open roads in England were governed by the RTTC – Road Time Trials Council with their handbook of the time bursting at the seams with rules.

But as author Jones points out, if the RTTC were so worried about the rules regarding competitors gaining advantage from passing motor vehicles then why sanction racing on what were motorways in all but name?

And a man who wore an Afghan coat and ear ring was never going to receive the approval of ‘committee’ with all of his brushes with authority well documented here.

What those RTTC dudes would make of Marcin Bialoblocki riding the Giro one year then their 25 mile championship the next would be interesting to hear.

And whilst Marcin pumps big watts it’s hard to imagine him beating the best kilometre riders of the day.

But that’s exactly what Alf did; spurred by one of his ‘pure trackie’ rivals telling him before the event that as a ‘tester,’ he was wasting his time riding.

There’s plenty in the tome about Alf’s colourful band of mentors and disciples; Alan Shorter, Alan Rochford, Barry Chick, Ken and Alec Bird – no ‘grey men’ in that list.

Some things could be better explained, like why Derek Cottington’s 50:47 ride, 13 seconds inside Alf’s record at the time of 51:00 minutes was disallowed.

The fastest 12 riders in those days were supposed to be seeded on the 10 marks, fastest off 120, second fastest on 110 and so on with the next 12 fastest on the five marks in between.

The organiser instead set the field like a handicap race with Cottington scratch chasing a succession of marginally slower riders at one minute intervals.

I remember seeing the start sheet and thinking; ‘hold on a minute… that ’25’ could easily have ended in a ‘bunch kick.’

And there’s a wee bit of confusion between ‘championship’ and ‘competition’ record.

But let’s not ‘nit-pick,’ anyone who takes the time to document Alf’s life and achievements deserves nothing but plaudits.

Albeit it would nice to know a bit more about the reasons for all those changes of club and perhaps more time spent talking about his family – or should that be his ‘dynasty?’

There’s a picture of his bonnie daughters but little mention of offspring in the text.

On the subject of images there are some new ones to me among those from Cycling Weekly we’re familiar with from those carefree days in the 70’s.

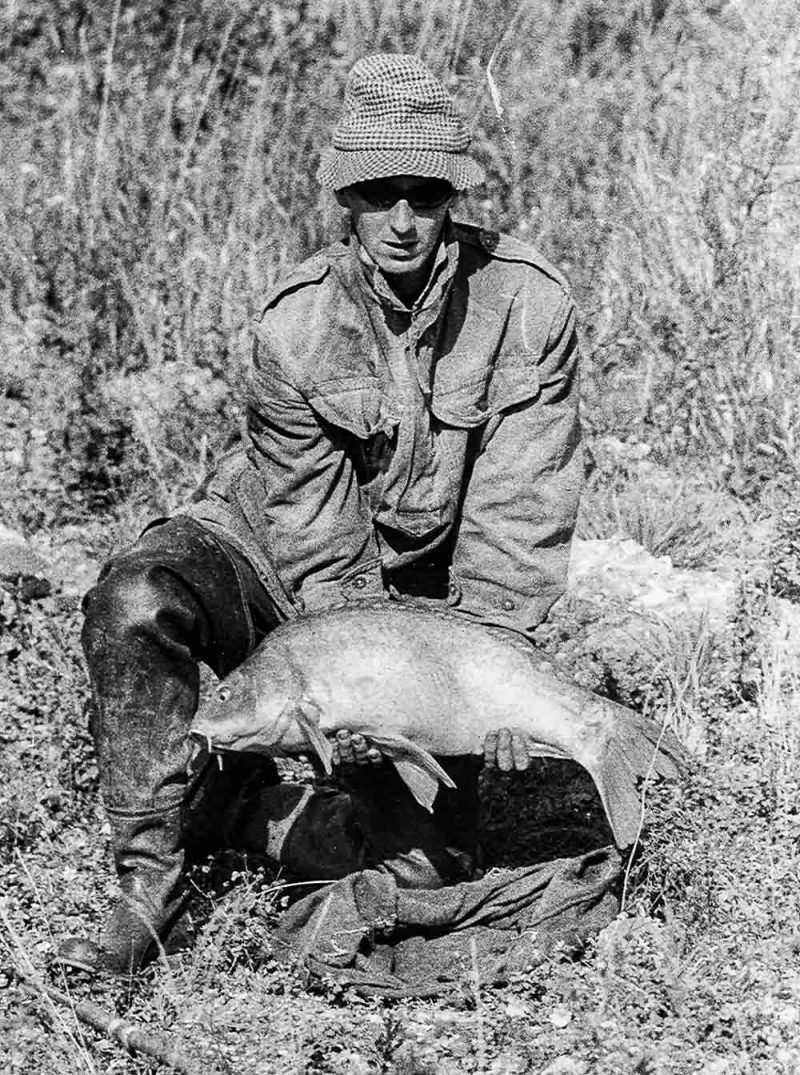

And no epistle about Alf would be complete without mention of his carp fishing – and bikes.

Clement silk 3 tubulars and fragile white strip Clement 1 track tyres, 57 rings, titanium axles, drillings, ‘fag paper’ clearances, they’re all here.

As is the fact that Alf was one of the very first to understand the vital importance of aerodynamics in the quest for time trial speed.

Back in the 70’s you couldn’t just go out and buy a ‘Rohan Dennis replica,’ no matter how much money you had.

Alf’s bikes – in particular “the speed machine” on which he rode to that legendary first “49” were ‘one offs’ crafted by dedicated artisans as offerings to their Deity, the Speed King, Alf.

Future print runs might include an appendix listing all of Alf’s achievements, including his other silver medal in the 50 mile championship which receives no mention?

But minor ‘anorak Ed’ criticisms aside, this book is well worth a read.

And whilst a mere mortal like me should never question ‘The King,’ late in the book he says he has ‘no friends.’

Not so, Mr. Engers, there’s a whole generation of us out here who love you; you were everything we couldn’t be.

We Like Alf.

* * *

Author Biography

Paul Jones is an occasional racing cyclist who struggles to balance the demands of writing about cycling with doing some actual cycling. He appeared in the same race as Sir Bradley Wiggins, Geraint Thomas and David Millar in the 2014 National Time Trial Championships, once scraped a 49-minute ’25’ and has won a couple of hill climbs and time trials in the South West of England.

His first book explored the niche and deranged world of the hill climb and is seen as the definitive (and only) work on the subject. His new book, “I Like Alf: 14 Lessons from the Life of Alf Engers”, is a biography of mythical folk hero Alf Engers. Beyond that, he has an obsession with time, social change and people, and he tries to explore this in his writing. In his spare time he is an English teacher.

Praise for “I Like Alf”

“This is incredible! I devoured the first chapter within minutes, it has a great narrative and style. He’s captured the enigmatic Alf and the period in question like no other.”

Keith Bingham, Cycling Weekly

“The prose is intelligent, the narrative addictive and the author’s prescience in framing the life of one of British cycling’s great characters commends it to everyone who follows the sport.”

Brian Palmer, thewashingmachinepost