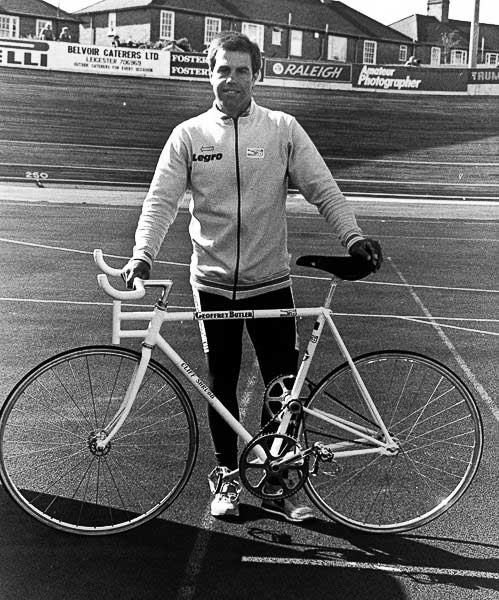

Dave Le Grys has been on the British track scene since I was a junior — that’s a long time. We thought we’d best have a word with the man who was winning track medals in 1973 and nearly 40 years later is still winning them.

Le Grys was born in Surrey, 56 years ago; he started cycling at the age of 12 and when he was 15 his parents immigrated to New Zealand.

That’s where we take up the story.

You were New Zealand junior sprint champion in 1973, Dave?

“Yes, nearly 40 years ago!

“I was offered New Zealand citizenship because they wanted me to ride the Commonwealth Games, which were in Christchurch the following year.

“But in my heart of hearts I wanted to return to the country of my birth — and that’s what I did.”

Remind us about your amateur career, back in the 70’s.

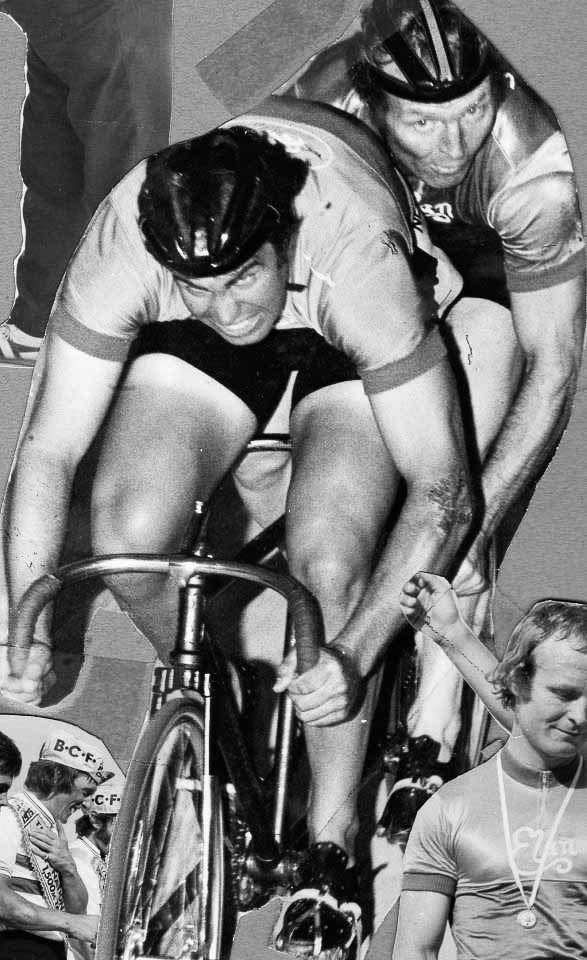

“I was the eternal silver medalist in the individual sprint — Trevor Gadd was my main rival back then.

“I made big gains in the tandem sprint; but my chances as a Worlds contender in that event came to an end in the Commonwealth Games at Edmonton, Canada in 1978.

“I was riding with Gadd and we crashed in the finals, I broke my back and had to have a lot of treatment and operations.

“I rode the kilometre as well as the sprint and tandem — and I wasn’t a bad road rider either,: I won the Perf’s Pedal race and Wally Gimber early season events in England.”

After you’d recovered from your back injury, you turned pro.

“I was offered a decent salary to turn pro and won the pro sprint four times, as well as the keirin a couple of times — I also found time to break the British land speed record for a bicycle at 110 mph behind a pace car.”

And then you came back as a master?

“I’ve won 21 world titles as a master, the most recent being in the 500 metres time trial on Manchester velodrome.

“I’ve lost count of how many British master titles I’ve won.”

What was the attraction with the tandem?

“I was Dave Rowe who got me into it — we won a couple of British titles together but that part of my career ended with that crash with Gadd in Edmonton.

“We had a front wheel blow-out at high speed and I had to be air-lifted to hospital.”

What’s your proudest sporting achievement?

“I ran five London marathons and got down to 2:38 — not bad for an old sprinter with a bad back!

“I did duathlons and triathlons too, but that 2:38 is probably what I’m most proud of.

“Bike-wise it’s probably my most recent win in the 500; a year ago I had a really bad crash in a points race — one of those ones where there was nowhere to go and I went right into it.

“Among my injuries was a punctured lung and doctor warned me that I’d never race again; so to come back from that to win was something special.”

How do you retain motivation to ride the masters’ events?

“If you’re coaching people it’s good to be able to practice what you preach!”

Why go into coaching?

“It goes way back to before I broke my back, you had to fight your corner to be a sprinter back then; British Cycling wasn’t interested — it was all about the endurance events.

“I ran one of my marathons to sponsor a warm weather training camp for the sprinters.

“I have a passion for sprinting; I was sprint coach and fell out with the national coach, Doug Dailey — I selected Paul McHugh for the Commonwealth Games but Dailey de-selected him.

“That was the start of the demise of McHugh’s career; he was a very promising rider — I’d had enough after that happened [McHugh is the only rider to win both the British junior and senior sprint titles in the same year; he also held the British 200 metres record with 10:84, outdoors at Leicester].

“I said to Dailey; ‘one day the sprinters will rule the world,’ and when you look at Chris Hoy and Co. you can see that I’ve been proved right.”

What’s your basic coaching philosophy?

“Never say die!

“There are lots of good athletes but attitude and mentality are the things — getting people’s minds right.”

Tell us about the Neuro Linguistic Programming which you practice.

“It’s about the old half empty/half full thing and about building rapport with a rider, understanding them.

“I’ll give you an example; if a rider is going up for a sprint heat where he thinks he’ll be beaten and is very nervous and up tight, he doesn’t want to hear; ‘you can do it’ because he doesn’t think he can.

“You’re better to say to him; ‘you aren’t gonna win this’ — that defuses the pressure; but then you say; ‘but let’s give him a fight and make him work for it.’

“Now, he’s thinking about fighting, not getting beaten.”

What would you rate your biggest coaching success?

“Ross Edgar, when he was 15 I turned him into a sprinter and then passed him on to the WCPP.

“We still keep in touch, talk about his training.”

You must have noticed a huge difference in equipment?

“I can still do 11.1 at 56 years of age; if you stuck me back on a steel bike then that would be 12.1.

“The indoor tracks, the carbon frames, the discs, the tri-bars all make so much difference.

“If you take tri-bars alone, they’re worth 0.1 of a second per lap.

“When I came back to the bike I did some time trialling, I rode a 56 for a 25 with tri-bars; that would have been unheard of for me with a normal road position.”

Do you think that sprinting is too sanitised, now?

“Definitely, it’s meant to be gladiatorial, physical and tactical; if you come off-line now you get disqualified.

“It’s faster now because it’s indoor but the UCi have gone over the top with the rules.

“When I’m coaching guys on the track, if you make contact with them, they’ll scream!

“You should be aggressive, not dangerous – if you can ride your bike then you shouldn’t crash.”

What would you change about the UK track scene?

“Because we have world champions it looks like the scene is great; but the triangle is upside down.

“We’re breeding and building champions but the infra-structure is collapsing — it’s too elitist.

“Take the British Nationals; there are four national teams riding them — the normal club riders have no chance.

“The problem is that whilst a few kids can go up through the Olympic Development Programem to the U23 squad, if they don’t make those squads then they’re lost to the sport.

“If the lottery funding is pulled then it will all collapse — I’m not aware of any rider who has continued after they’ve been booted off a squad.”

What have you still to do in the sport?

“I want to continue to race whilst I’m still capable of getting results – but one day I’ll be happy to ride my bike through the lanes.

“And I want to help the sport — I’ll continue my coaching.”

Regrets?

“Loads; but we are our own destiny and what cycling has given me more than makes up for any regrets.”