There is no doubt that Biniam Girmay’s win for Intermarche Wanty on Stage 10 of the 2022 Giro d’Italia was a historic one.

However, contrary to what many have said, it is NOT the first stage win by an African in the race.

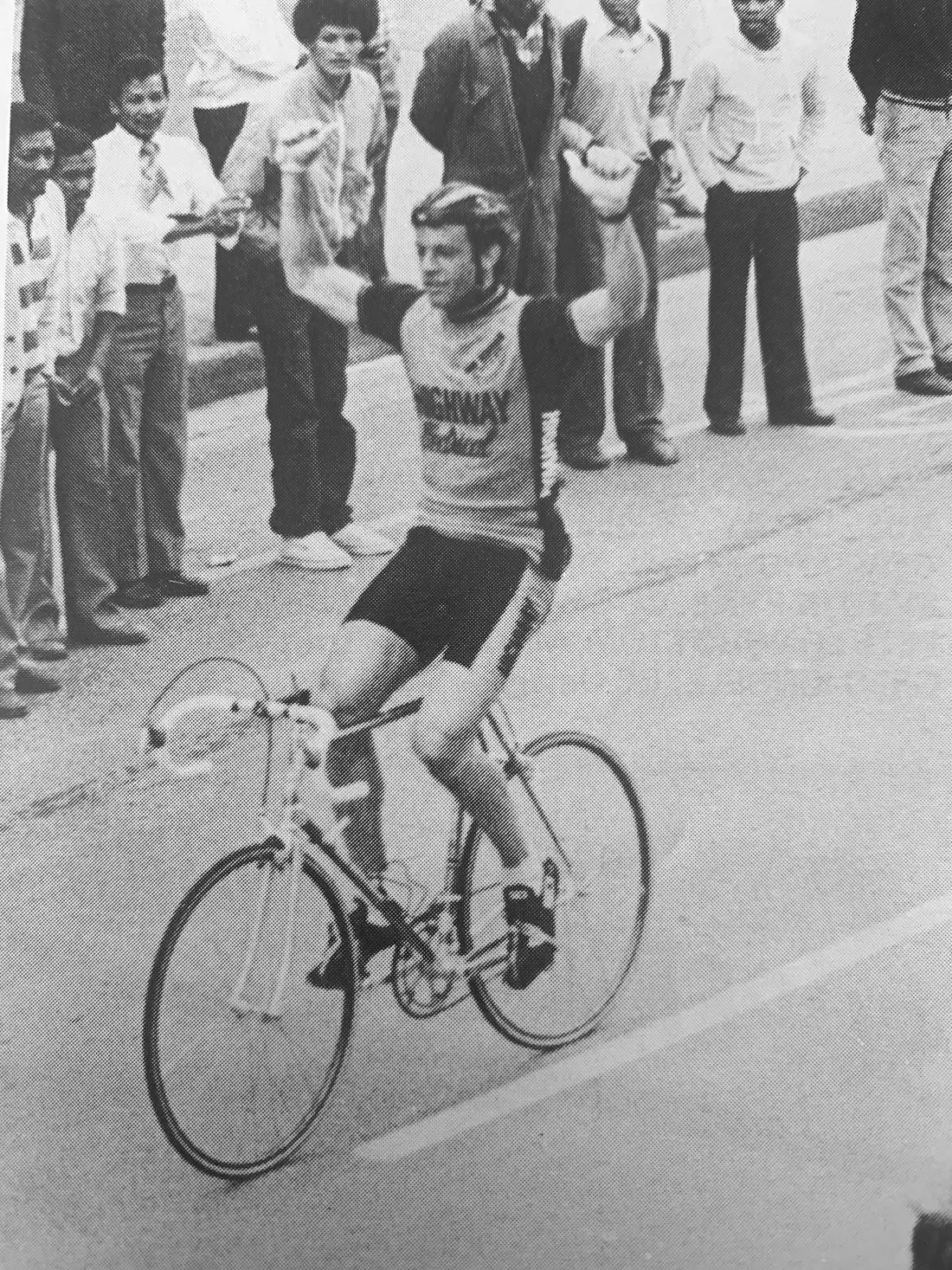

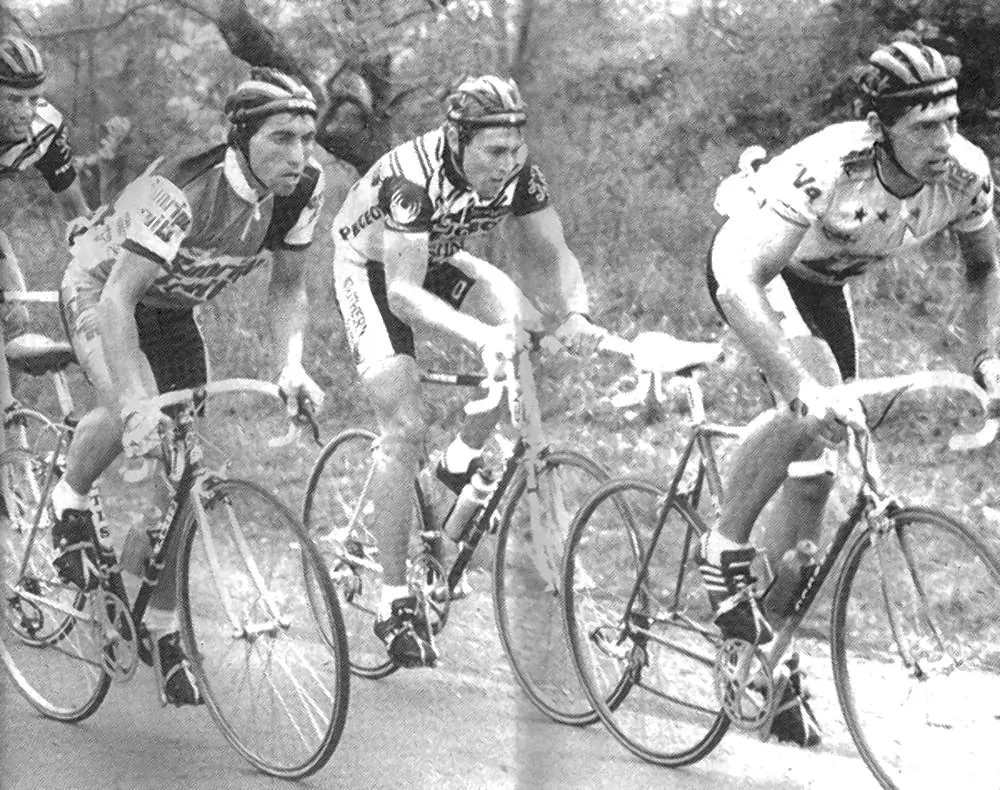

On May 4th 1979, in the Giro, Stage Seven, Chieti to Pesaro over a massive 252 kilometres, Peugeot’s South African rider, Alan van Heerden became the first African to win a Grand Tour stage.

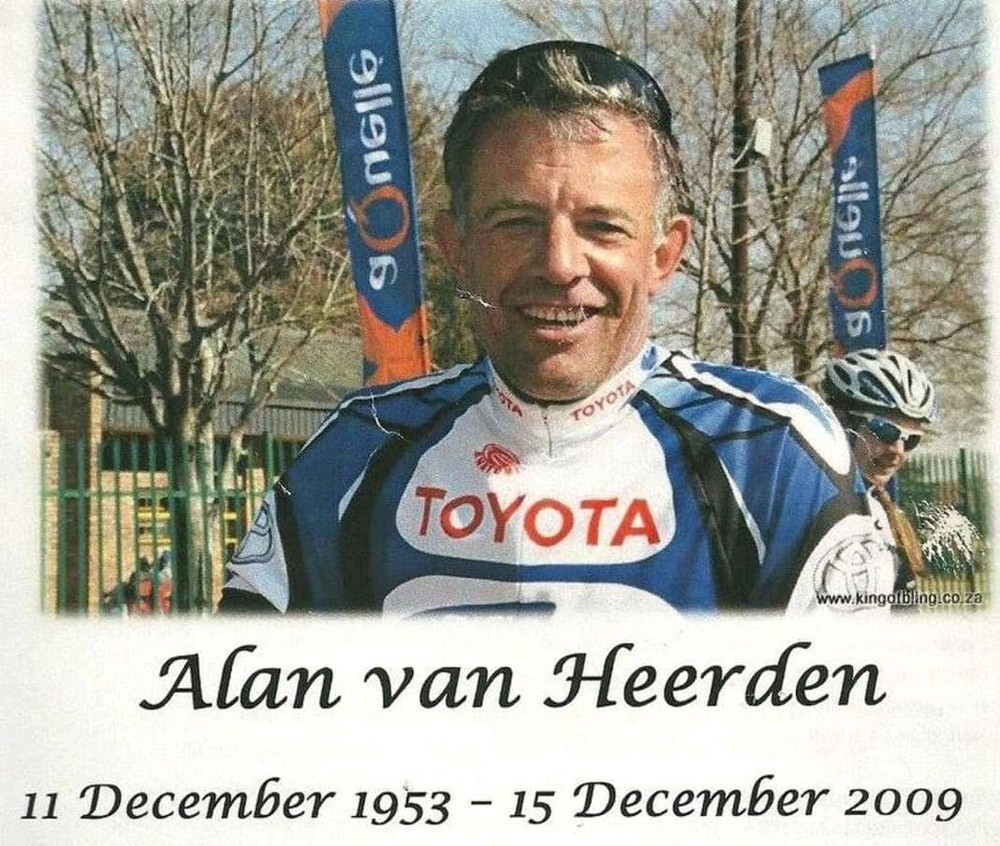

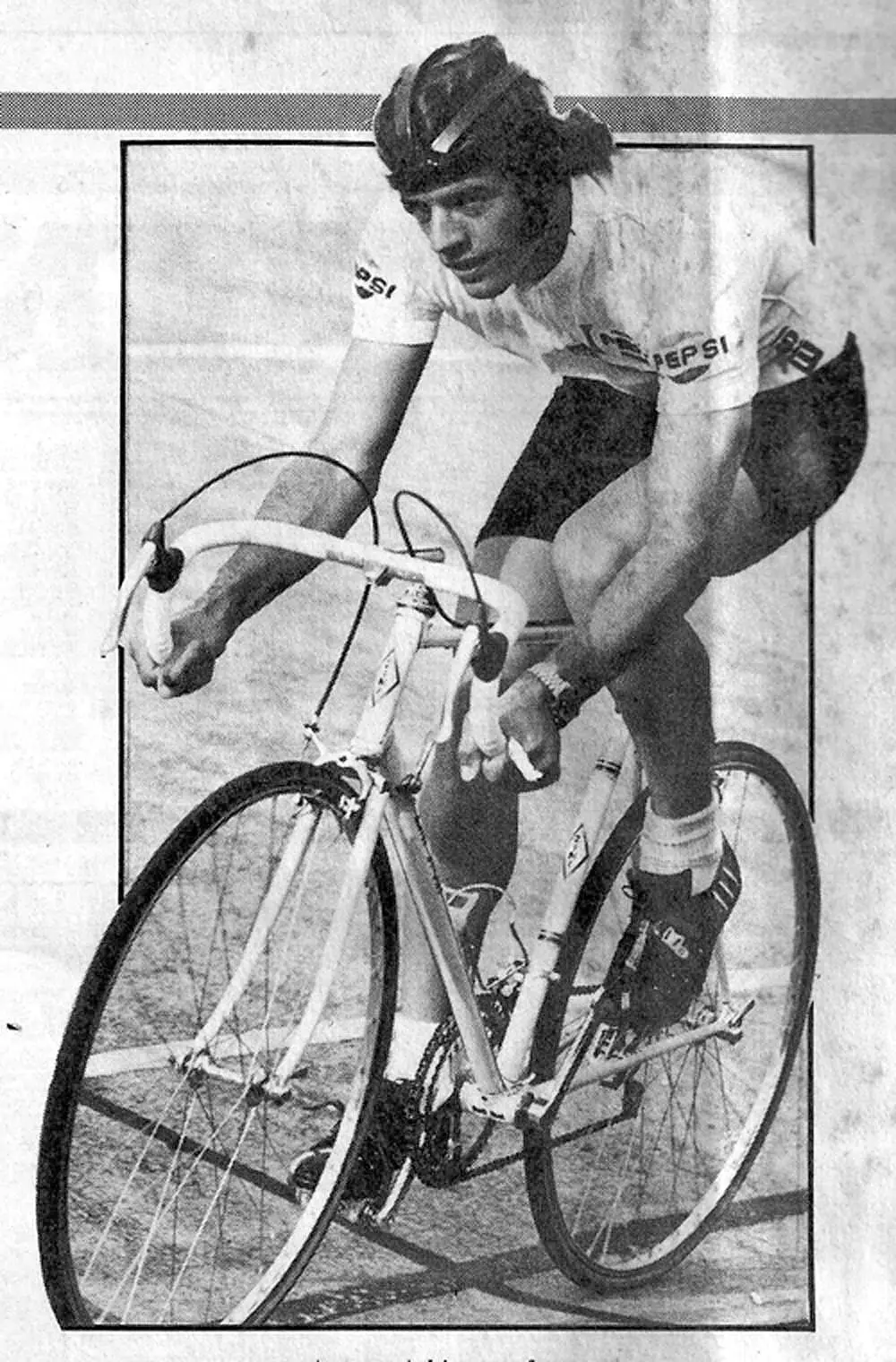

Sadly, van Heerden died in a road accident in 2009 at the age of 56 but his wife, Wendy very kindly agreed to talk to me about her life together with a man who, although relatively unknown to European cycling fans is a legend in South African cycling circles; ‘The Idol’ they called him.

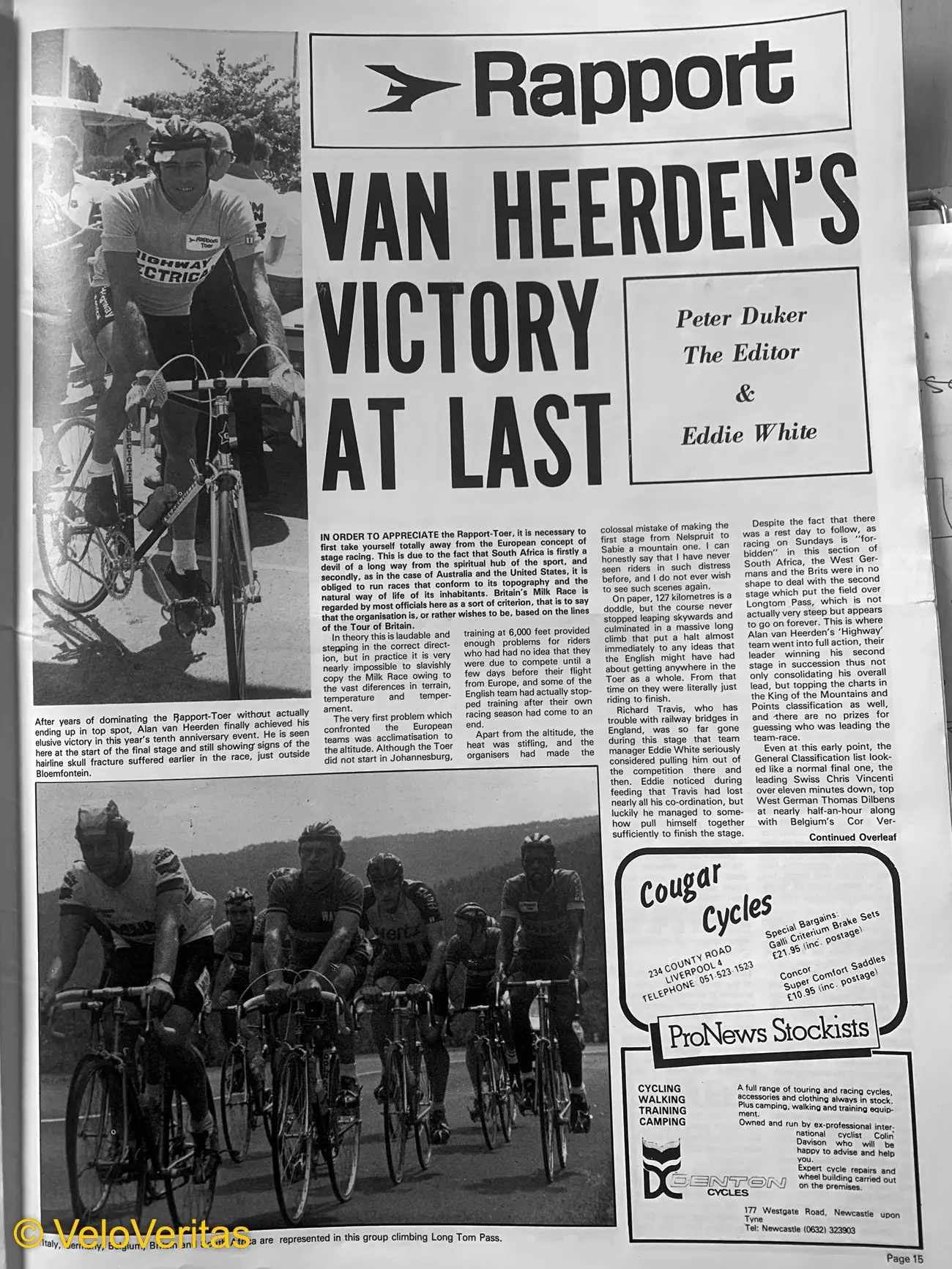

Apart that Giro stage win his performances in his home Rapport Tour are stunning; in 17 participations he achieved two overall wins, 66 stage wins, 11 overall points classifications and five king of the mountains titles.

The Rapport Toer, over as many as 20 stages, is famous for being the catalyst in Sean Kelly turning professional – racing under an assumed name in those days of apartheid when international sportsmen were not supposed to compete in South Africa – he was ‘rumbled,’ his chance of Olympic selection gone it hastened his move into the pro ranks.

We opened by asking Wendy how she and Alan first met?

“I first met him when I was very young and still at school, my brother and cousin were into cycling and used to go to the track racing in Johannesburg – track racing was big in the city then.

“We went then out for a while but then got together again when I was 19 years old, we were married when I was 25 years-old.”

France – that must have been a big adventure?

“Alan actually spent six weeks in Italy before we went to France; but he was a bit of a home bird and hated it there, he didn’t like change.”

France, Peugeot, tell us about that.

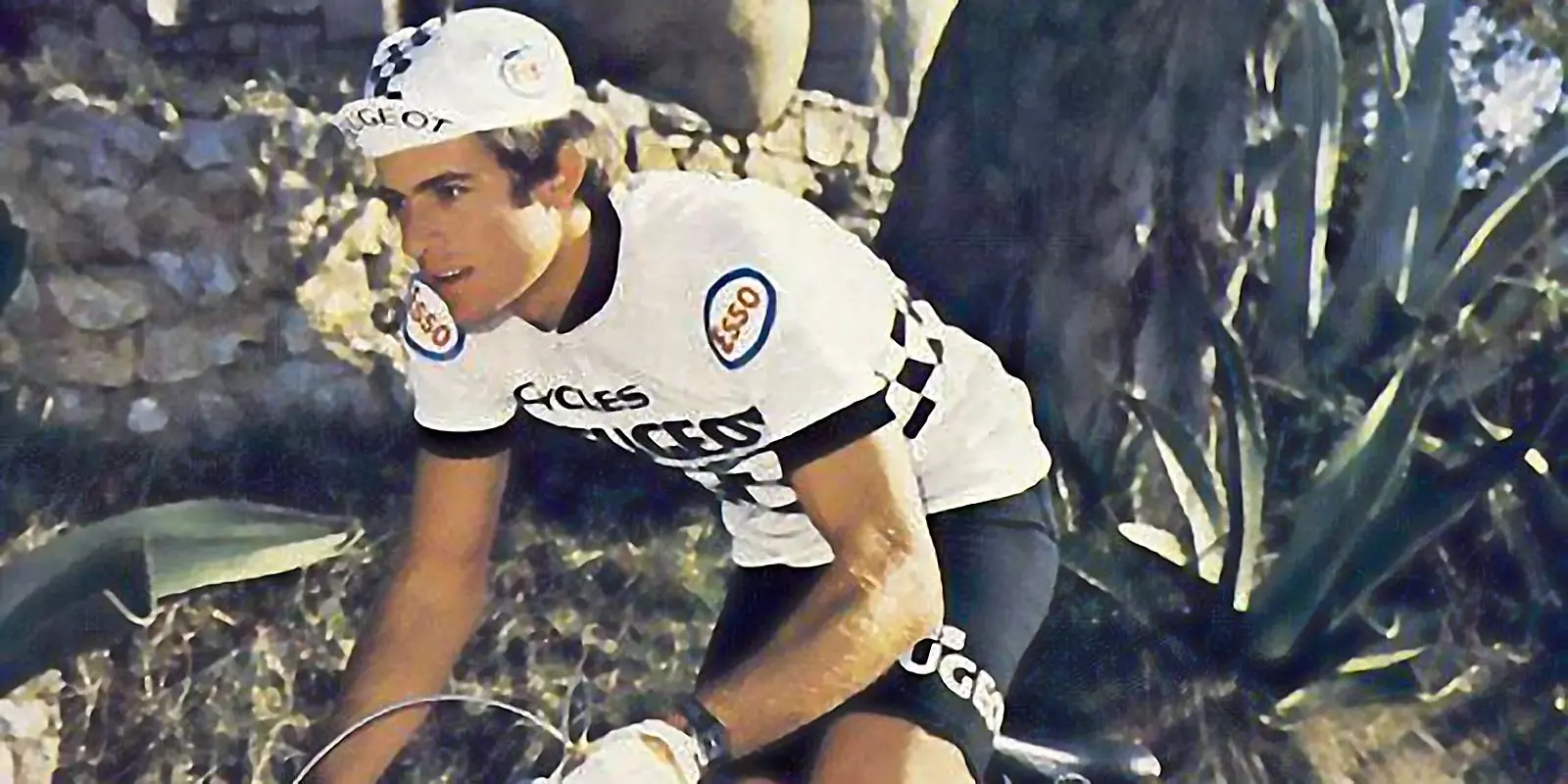

“Initially he was with the ACBB, the Peugeot amateur ‘feeder’ team, we had a one bedroom flat in Boulogne-Billancourt which was next to the main apartment.

“Phil Anderson was there, Paul Sherwen too – and Robert Millar.

“Alan had an arrangement with the South African press that they wouldn’t mention his name – remember that this was at the height of the apartheid situation and South African athletes weren’t allowed to compete internationally.

“Alan rode on an Australian licence on the premise that his mother was Australian – but she wasn’t.

“He did very well but it was awkward when he won and had to speak to the media, with that strong South African accent of his!

“After he was third in the amateur Paris-Roubaix the English anti-apartheid activist, Peter Hain (who subsequently went in to politics and is now a Labour Peer in the House of Lords) and the South African anti-apartheid campaigner, Sam Ransamy got wind that Alan was racing in France and there was a big controversy.

“However, Alan had already signed as a full professional with Peugeot. The team was pretty influential in those days so he was able to ride for them.”

“To start with they wouldn’t give me a visa but eventually I moved to Paris; I wasn’t particularly happy there because Alan was away a lot.

“I was much happier when we lived in Belgium, St. Niklaas. Afrikaans is quite close to Dutch so I was able to pick up the language.

“Belgium was pretty old fashioned compared to South Africa which, whilst it was a third world country, was much closer to US culture than European.

“But the Belgians were very friendly, warm and much more sympathetic to our situation than the French who were a bit cold, although I suppose the language barrier didn’t help.

“But Alan wasn’t a political person at all.

“Phil Anderson, Robert Millar and another South African rider, Robbie all lived up there.

“Alan picked up French, the language of the Peugeot équipe, pretty quickly and was soon accepted as part of the team.

“Hennie Kuiper, who in 1980 had just finished second in the Tour de France used to train with Alan and they’d go to races together; Kuiper used to always get Alan to drive – which he hated.

“In Belgium Alan also trained with the De Vlaeminck brothers and he was friendly with Francesco Moser, they’d go to criteriums together.”

What do you remember about that Giro stage win?

“I didn’t witness it, wives weren’t allowed anywhere near races in those days.

“I was actually in London at the time, Alan’s parents had come over and I was showing them round Europe.

“Alan phoned from Italy, he was very excited, the first African to win a Grand Tour stage and at 252 kilometres it was the longest stage of the race.”

Why did you return to South Africa?

“Alan was doing very well, he was a great kermis rider but he hated the North European climate, the wind, rain, hail, snow – I mean, in South Africa, if it rained, they cancelled the race.

“He had a contract for 1981 but was riding a kermis on a terrible day when the sleet was driving horizontally, there was a descent in the race and a race car had parked up, he saw it but was so cold he couldn’t pull his brakes on and went through the rear windscreen.

“He was a very impulsive man and right then decided we were going back to South Africa – it was a decision he’d later come to regret.

“But he hated training and racing in the cold and rain, his early season training in the South of France was fine weather-wise but up in Northern France and Belgium in the spring, the weather was terrible.

“In South Africa we were used to ‘braii culture’; eating outside. You’d say ‘barbecue’ but a braai just isn’t considered a braai if cooked on a gas grill.

“The fire also remains lit for the duration of the braai, even after the food’s been cooked. Guests will gather around the fire after eating and spend the rest of the day or evening there.”

Did he get much hassle from the UCI?

“There was a bit of a ‘to do’ with the Australian Federation because he was racing on an Aussie licence – but as I said, once he signed with Peugeot it was put to rest.

“Back in South Africa there was no pro racing so upon his return they introduced pro racing, most of the guys worked but raced for cash prices.”

His Giro stage win apart his most famous performances were in the famous Rapport Toer in his native South Africa.

“I can’t remember all the statistics but he won it overall twice and won a lot of stages – but what I do remember is him being involved in a bad crash at Bloemfontein and cracking his skull then leaving the hospital to finish the race!”

I believe he had a cycle business in South Africa?

“Yes, and it was successful but we missed Belgium and the Belgians, we had good memories of there – not France though.”

Did he have any regrets?

“He did regret that decision he made to quit Europe after he had that crash, he was a very good kermis rider and used to say to me; ‘I wish I had stuck it out, made a name for myself and made money…”

With thanks to Wendy for giving so freely of her time and her memories.

* * *