With the sweet smell of ‘ganja’ wafting out of the windows of at least two of the Dysart High Street flats and into my nostrils, Barney Ribble and I set off for East Wemyss and the Fife Coastal Path once more.

The last time we headed east we finished up at MacDuff Castle so we’ll pick it up there.

But before we do, we’ll stop off at West Wemyss for a memorial that I only recently noticed.

It’s in memory of the five local men who, in January 1941 went out to prevent a sea mine which had broken free from it’s moorings from drifting towards the village but sadly lost their lives when the device exploded.

Incidents like this weren’t reported in the war time press for fear of, ‘damaging civilian morale.’

Just across the way from MacDuff Castle up on the main road is a reminder of the days when South Fife was at the heart of the Scottish coal industry.

The Wemyss family invested heavily in collieries and their own railways to transport the black gold from the pit head to the docks at Methil – millions of pounds worth of the stuff.

From East Wemyss the Coastal Path follows the flat and fast line of the old red gravelled tram line to Buckhaven.

In my ignorance I thought that the name came from something to do with deer – as in ‘buck’ and ‘hind,’ which is what us locals call the town – ‘Buckhind.’

But it actually comes from Norse; a ‘hyne’ was a haven between the rocks where boats could be safely hauled ashore and ‘buck’ meant to ‘roar.’

And there’s a connection with the cycling Heartland of Belgium in that Flemish refugees, escaping religious persecution, settled here in the 16th century.

Buckhaven used to have wonderful beaches but as with Dysart beaches and the Frances Colliery, ‘redd’ from the long gone Wellesley Colliery put paid to the golden sand.

The path ‘goes urban’ through Buckhaven but not before a reminder of another 1941 sea mine tragedy, this time eight poor souls lost their lives to one of the devilish devices.

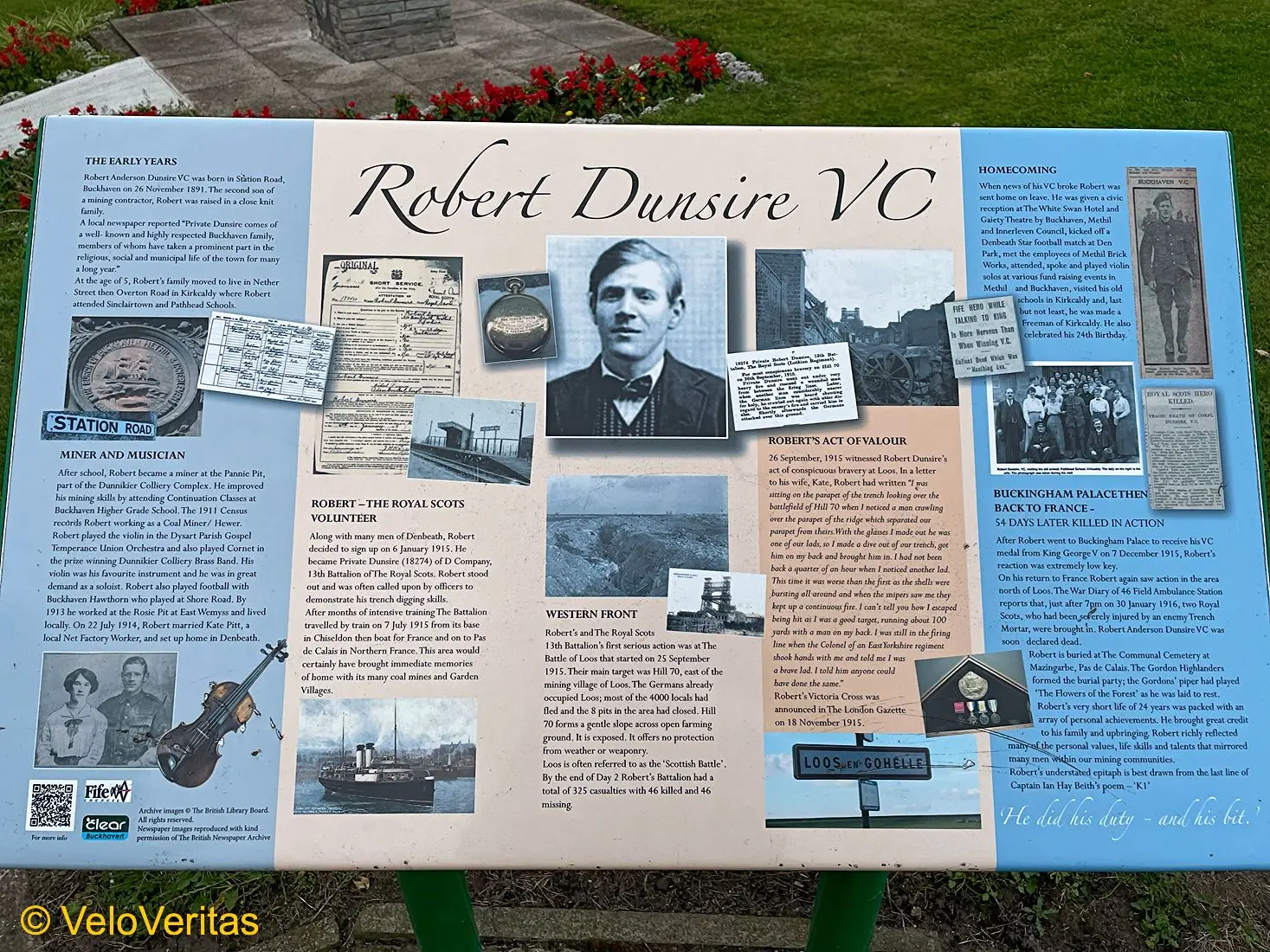

At the entrance to Toll Park where your journey across town starts there’s a memorial to one of the town’s most famous sons, Robert Dunsire who was awarded the Victoria Cross for bravery in 1915, rescuing two comrades from no man’s land, carrying them on his back to safety under heavy enemy fire.

‘They didn’t weigh any more than a sack of coal,’ explained ex-miner Dunsire; sadly, he didn’t survive the conflict.

Where the old Wellesley Colliery stood is now a car park, overlooking the big fabrication yard, it used to be oil related works but wind farms are the thing now.

There’s no plaque to mark the site of a pit which gave employment to some 1,500 men.

The Wellesley canteen was open to public and on the school summer holidays back in the early 60’s when I used to go out with my dad in his wee works van we’d stop in there for sausage rolls and tea at knock down prices – life was simpler then.

Just along from the site of the Wellesley is the former Swan Hotel, the Swan is the symbol of the wealthy Wemyss family who owned many of the local pits and railways before nationalisation.

There’s a steep brae down from the Swan to Lower Methil; one of Dave’s work mates reckoned there wasn’t a man alive could ride a bike up that brae!

He’d obviously never heard of those 60 kg. Colombian boys, albeit I had to walk it one time when Barney’s battery died on me.

At the east end of Buckhaven and Methil is the Bawbee Bridge, crossing which takes you into Leven, a onetime Mecca for Glasgow holiday makers.

It’s called the Bawbee Bridge because a ‘Bawbee’ was an old Scottish coin and that was the fare the ferryman used to charge to row passengers across the River Leven in the days before there was a bridge.

The river rises in Loch Leven, which in a stunning feat of Victorian engineering was lowered by some four feet, sluice gates installed and the river ‘straightened’ to provide a consistent flow of water for the two dozen paper and textile mills along the banks.

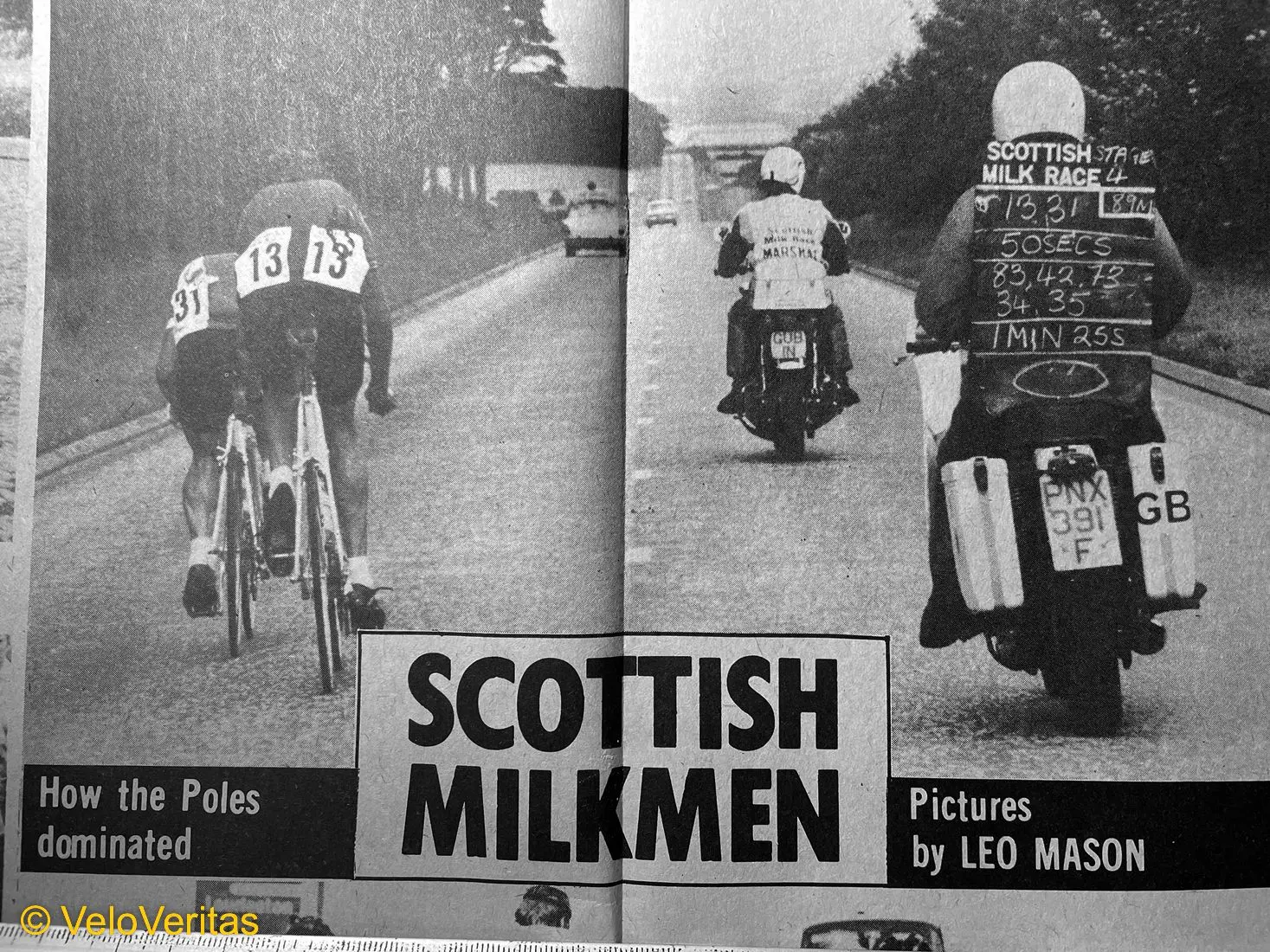

Leven Prom was the scene of Tour of the Kingdom finishes in the 90’s and Scottish Milk Race finishes back in the 70’s; in the 1975 edition Dave and I were positioned on the Stanin’ Stane Road, the long, straight undulating road which heads east into Leven from Kirkcaldy.

At the head of affairs was that late, great, stocky bear of a man, Ryszard Szurkowski of Poland, glued to his wheel and trying in vain to get some shelter from the squat form of Szurkowski was big Phil Griffiths.

Phil was always quick-witted with plenty to say – but not that day; Szurkowski had him on the rack, en route yet another stage victory.

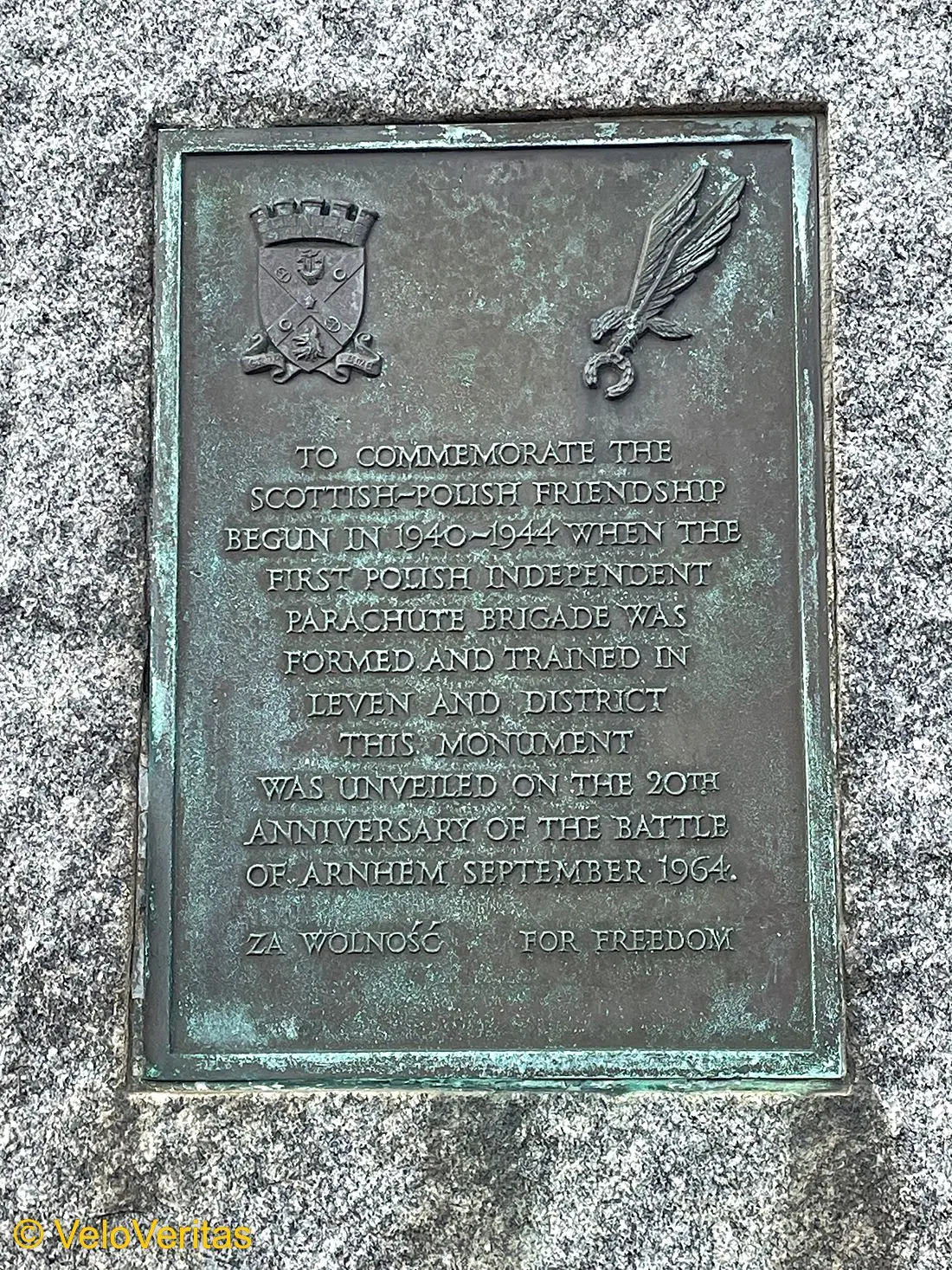

Leven is no stranger to Poles though, the 1st Independent Polish Paratroop Brigade trained there before their involvement in the disaster that was Arnhem.

Continuing past Leven takes you into the sand dunes which separate Lundin Links golf course from the beach.

There’s much of it rideable; that would be ‘all of it’ if you were Freddy Maertens and the Flandria boys back in the 70’s – but not if you’re 67 years-old, even with an electric motor in the rear hub.

And on the subject of the motor; some chap on Facebook was sounding off that ‘e Bikes’ are a curse. All I can say is that it’s a joy to get to the top of the village and not to have to stop and pretend I’m looking at my mobile phone until the pain in my hip eases.

In common with many beaches in East Scotland, Lundin Links has concrete block anti-tank defences to thwart potential World War Two German landings; albeit it’s a lot further across the cold North Sea than it is across the English Channel.

If you venture inland off the path to Upper Largo you can still see the canal dug by local legend Sir Andrew Wood from his home to the local church so he could travel by barge to the Sunday service.

It’s been said this is a myth, but as the famous photographer, Robert Capa once said; ‘never let the truth stand in the way of a good story!’

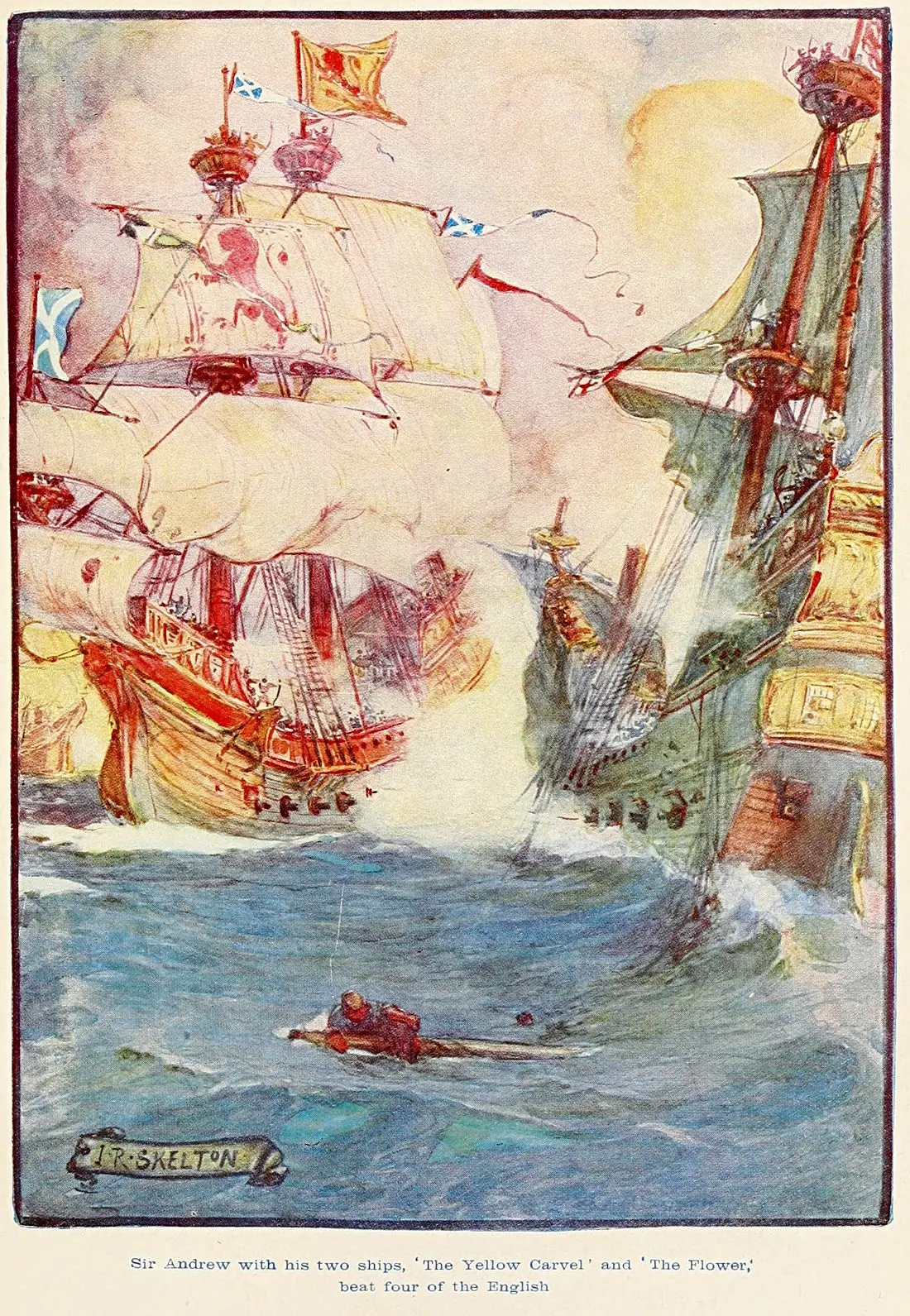

What’s no myth is that Wood twice defeated superior English forces in sea battles in the Firth of Forth in 1488/9 and was known as, ‘Scotland’s Nelson.’

Lundin Links runs into Lower Largo past the quirky and lovely gate of local artist Alan Faulds.

Journey’s end for this secteur is at the Alexander Selkirk birthplace statue, the inspiration for Daniel Defoe’s ‘Robinson Crusoe.’

There are two versions of why the Scot ended up on Mas a Tierra Island, part of the Juan Fernadez cluster off the coast of Chile; one is that he could see that the ship he was aboard, the Cinque Ports, was a ‘death ship’ and doomed so he asked to be put ashore.

The other is that he was a cantankerous fellow who his shipmates deposited there to get rid of his constant bad tempers.

Next time on the Fife Coastal Path we’ll go west again…

* * *

Check out Part One and Part Two of Ed’s journey on the Fife Coastal Path.