It was with much sadness that VeloVeritas heard of the passing of 70’s legend and former British Amateur Road Race Champion, Grant Thomas.

As our tribute to one of the coolest men ever to throw a leg over a racing bike we’d like to re-run our interview with the man. RIP, Grant.

* * *

First published on May 31st, 2010

Team Raleigh’s Dan Fleeman has set the interview up for us, and we’re sitting in the “Hotel Anonymous” in Walsall. A dapper, trim figure in blazer and slacks bounds up the stairs; it takes a moment to register – it’s our man, Grant Thomas.

Good words for riders from Viktor? They’re thin on the ground… Niko Eeckhout, Guy Smet, Hamish Haynes, Jack Bauer and maybe Jens Keukeleire get grudging acknowledgement. But there has to be someone he idolised, surely?

British amateur road race champion, winner of amateur Six Days and one of the best road men in Europe in the early 70’s. There were no budget airlines, no internet, no mobile phones – just the will to go and race against the best in the world.

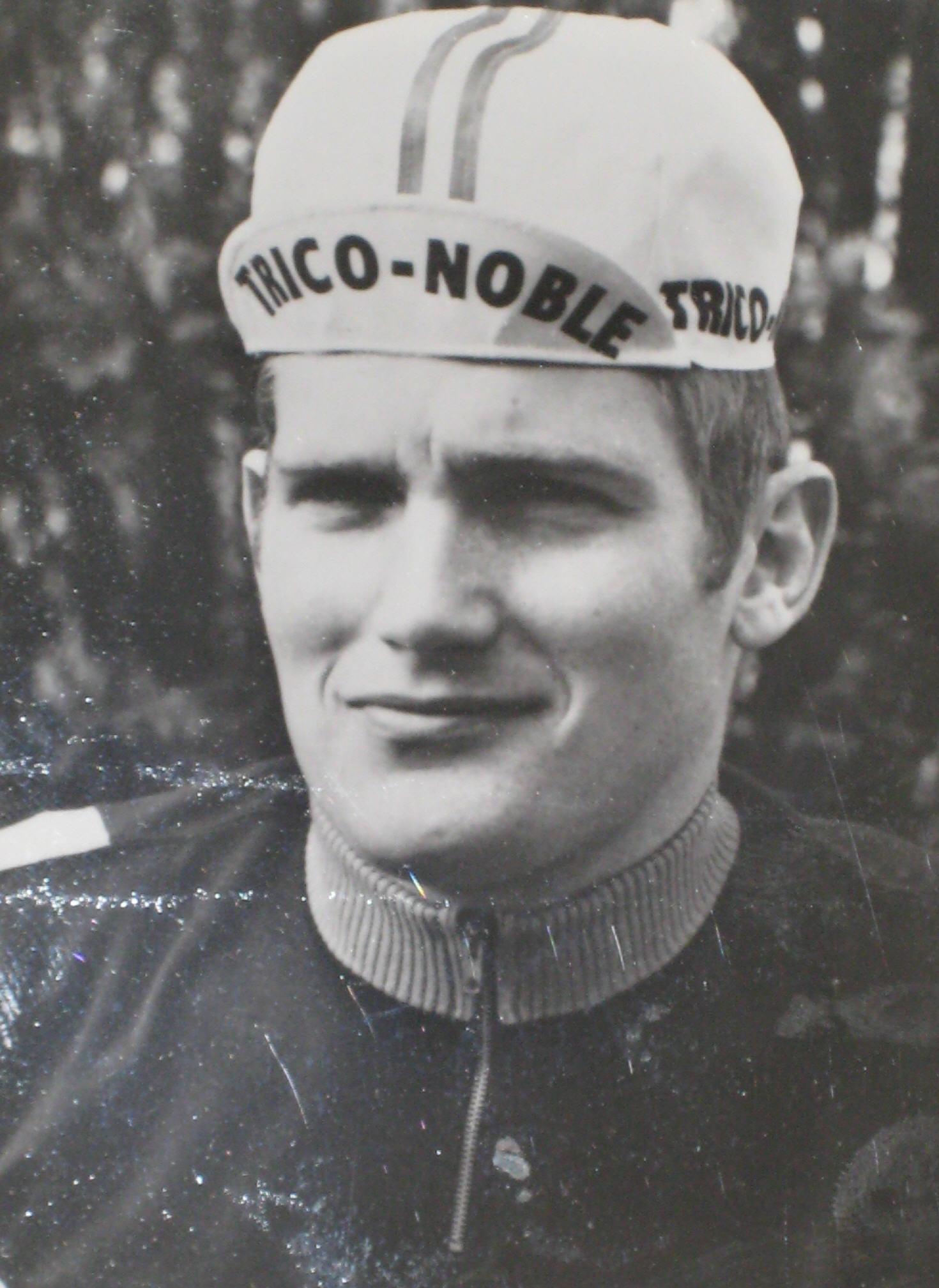

As Viktor put it; ‘he was the coolest – nobody looked better on a bike than Grant Thomas, he was everything I wanted to be in a cyclist.‘

* * *

Early Days

Grant was involved in the local brass band as a lad, it was part of the culture that each mine would have it’s own band, but music wasn’t what inspired the youngster. “My dad saved cigarette cards and I remember looking through them and being fascinated by the racing cyclist ones“, but that’s only a part of why Grant wanted to become a racing cyclist himself.

His dad was in the Cyclists’ Touring Club, the CTC, and Grant would often accompany him on weekend runs. “We’d go down to Weston-Super-Mare at 20 mph average. Walsall was a mining village and every lad had a bike, if you didn’t, you were cooped up here. Thing is, we used to see the racing guys when we were out, you could identify them by the ice cream flags they used to roll their tubs in, under their saddles.“

* * *

Early UK Racing

Grant’s racing went well, and he steadily progressed up through the ranks, so by 1968 he was short listed for the Mexico Olympics, on the track. “I hadn’t trained for the road, and I had to fit the bike in around studying for my HNC; we got holidays from college to study for the exams, and I’d use the time to go training in the mornings.“

In the late ’60’s, the top track riders of the day were Ian Hallam, Ron Keeble, Harry Jackson and Billy Whiteside, and Grant found himself in the team pursuit squad with them.

However, in the event, Grant didn’t travel to Mexico for the Games. “We had a trial, the squad was divided in two and we did a full distance team pursuit – 4:36 was the target. I think my team did 4:42 to the other team’s 4:38, and that was that.“

* * *

Moving to Holland

In 1969, Grant had completed his HNC, and started to wonder what to do next, when fate took a turn; “When college was out of the way we’d heard that a clutch of Brummie guys had gone to Limburg in Holland to race.”

Grant arranged to meet one of the guys, and he gave Grant a valuable first step – an address. “So Mick Bennett and I went off Holland, found the address and knocked on the door!“

The day the two of them arrived in Holland, the fourth edition of the Amstel Gold Race was being run, with Guido Reybrouck leading a Belgian clean sweep of the first seven places. All the villages on the race route were “in feest”, in festival mood, “but Mick wondered if all the flags were out for us. The family were having their tea when we arrived and I think they gave us some chips.“

Grant and Mick Bennet fixed up to stay with the family that evening, and that was it, they were organised. It was a culture shock as could be expected – not only living in a foreign country, but stepping up a level in the quality of the racing too.

Nevertheless, Grant got himself noticed. “I managed to scrape a top 20 in the Tour of Limburg; that caught the eye of the promoter Charles Ruys, and I got invited to ride some omniums after that.“

Ruys asked Grant; “what are you doing down here in Limburg? up in Brabant they ride twice as fast!“

Grant got an invite to ride the Omloop Van Het Waasland, a race based around the Flemish region bordering the Netherlands to the north, who’s capital is Sint-Niklaas. “We decided to move up to North Holland and got fixed up in lodgings at a village called Philippine. It was so small that when we first drove through it, we missed it, we had to turn the car and go back!“

The family Grant lived with looked after him and treated him really well, “like a son. Eventually they even bought me a car to go to races in, an Opel.“

Towards the end of the racing season, Grant decided to remain in Holland, rather than come back to England.

Together with another English rider, Terry Carroll, they both went to work in the sugar beet factory in the area. “It was hard graft, humping sacks of pulp seven days a week – we used to call it the ‘Sugar campaign’.”

Once the crop was processed for the day, the two of them would go out training. Sometimes, Grant would buy a train ticket and travel up to the Antwerp track for a session on the boards.

* * *

Getting it Together

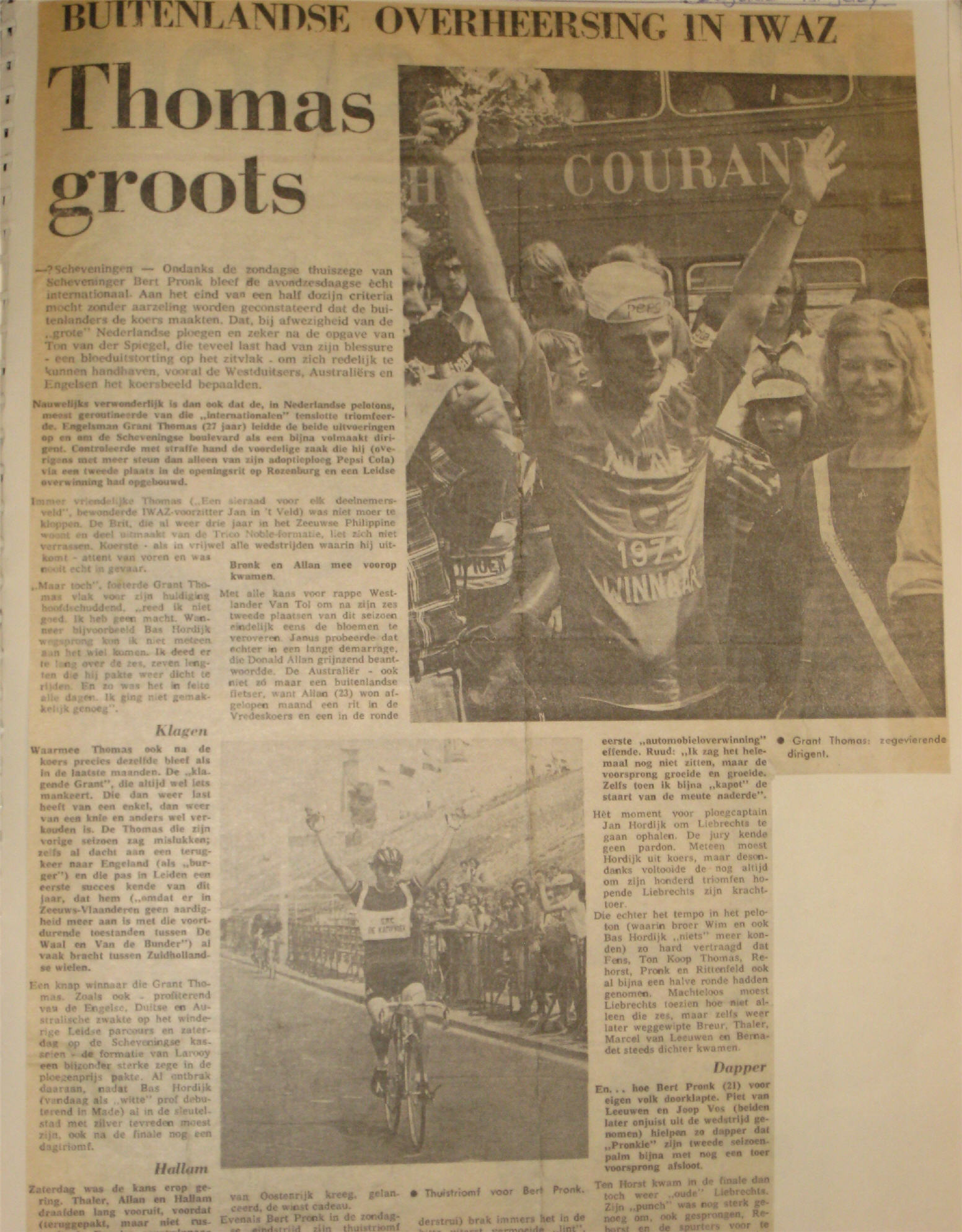

In 1970, Grant started to get it together, with a string of good results in major races; 16th in Het Volk, won by Frans Verbeeck, 3rd in the Ronde Mid Zeeland, 3rd in the amateur Henninger Turm, and 10th in the ‘trial’ race on the Olympic circuit at Munich. “I guested for the Trico Noble team and won a race for them in Luxembourg, so that got me a ride for them in ’71. It was strong team with precocious Dutch talent in it – guys like Cees Bal.“

For some reason Grant always had bad luck in the World Championships, and this year, with the Road Championships held in his own country, in Leicester, was no exception – Grant’s chain broke, ending his chances.

Three years later in Barcelona, a plastic bag jammed in his gears ensured the same end result. “I finished 1970 on a high though – I got 8th, 3rd and 2nd in three late season Dutch classics. To be honest, it wasn’t as hard towards the end of the season – in the spring, they’re all keen and raring to go; but it got me a lot of praise from the Wielersport magazine.“

In 1971, Grant went well from the start of the season, gaining selection for the Great Britain team for the Tour of Holland, the Milk Race and the Scottish Milk Race. “Trico didn’t like me being away from my race programme with them, but I won the big local classic for them so that made amends. In fact, the boss was so happy with me that he took me to Yugoslavia on holiday with him!“

* * *

No Olympics

Sadly though, Grant picked up an injury over the winter, and by May ’72 he realised that any chance of an Olympic berth was gone, so instead he rode a lot of criteriums. “The primes were good – you could come away from a race with the equivalent of £100 Sterling – that was a lot of money, back then.“

Grant tried to defend his title in the classic that he’d won for Trico the previous year but crashed whilst in the echelon and couldn’t get back on.

* * *

British Champion in ’73

Grant’s form coming into the 1973 season was up and down, and his inconsistency could be put down to the problems he had experienced over the winter with his stomach, but as he told us, “but when you’re up against it you have to summon up more from the soul!“

Riding the Felix Melchor stage race in Luxembourg seemed to be the turning point, and Grant felt he had some form following that, which he hoped to take into the British Championships. “I was in better shape, but I had a cold before the title race.“

Grant followed every move in the Champs, determined not to miss the winning move. “I went with everything that day, I wasn’t the strongest but I think I was the smartest. Dave Vose from the very strong Kirkby club came past me in the uphill sprint, but he died before the line and I re-passed him to take the title.“

It was around that time that Grant’s leg started to play up, and the following winter saw more problems for Grant, with him ending up in hospital with inflammation of the stomach, being kept in for for seven weeks and losing a lot of weight. “I got the all-clear late January but my weight kept dropping. I came back to England on holiday but I was a waste of space, I had no strength.“

* * *

Back to Blighty

Riding for the Birmingham Roads team in the UK in ’75, Coventry Olympic in ’76, then the all-conquering GS Strada in ’77 and ’78, Grant did well but was never the same again. “It’s like Pijnen said, he was never the same rider after he had problems with his tonsils – and Merckx was never the same after he had that crash behind the motorbike on the track.“

Grant didn’t go back to Holland to race because he knew he didn’t have the brute strength necessary to be competitive, the strength he used to have – although he did spend the winter of 1977 in Philippine, the spark was gone. “Racing in the UK isn’t like riding on the continent, it’s hard to get the motivation.“

* * *

A Pro in the UK

Despite never having taken out a professional licence in Holland, Grant turned pro for Falcon in 1979, but found it hard to get motivated for the events, such as 90 mile road races when there were only 18 or 20 other riders on the start line.

The 1980 season opener was at Aintree in Liverpool, but as Grant says, he “decided not to bother.“

He was working within two weeks, and the reason was that he felt that the UK pro scene wasn’t going aywhere. “It was Mickey Mouse, mostly short criteriums on tiny circuits.“

Asked why he didn’t turn pro when he was racing well in Holland as a young man, only 23 years old, Grant says that he simply didn’t think he was good enough yet. “When I was over there, the likes of Bal, Raas and Priem – who were only 18, 19, 20 years old – were dominant. I could mix it with them, but I was at my limit. If I hadn’t been ill when the Raleigh Euro Team started up, I might have considered that.“

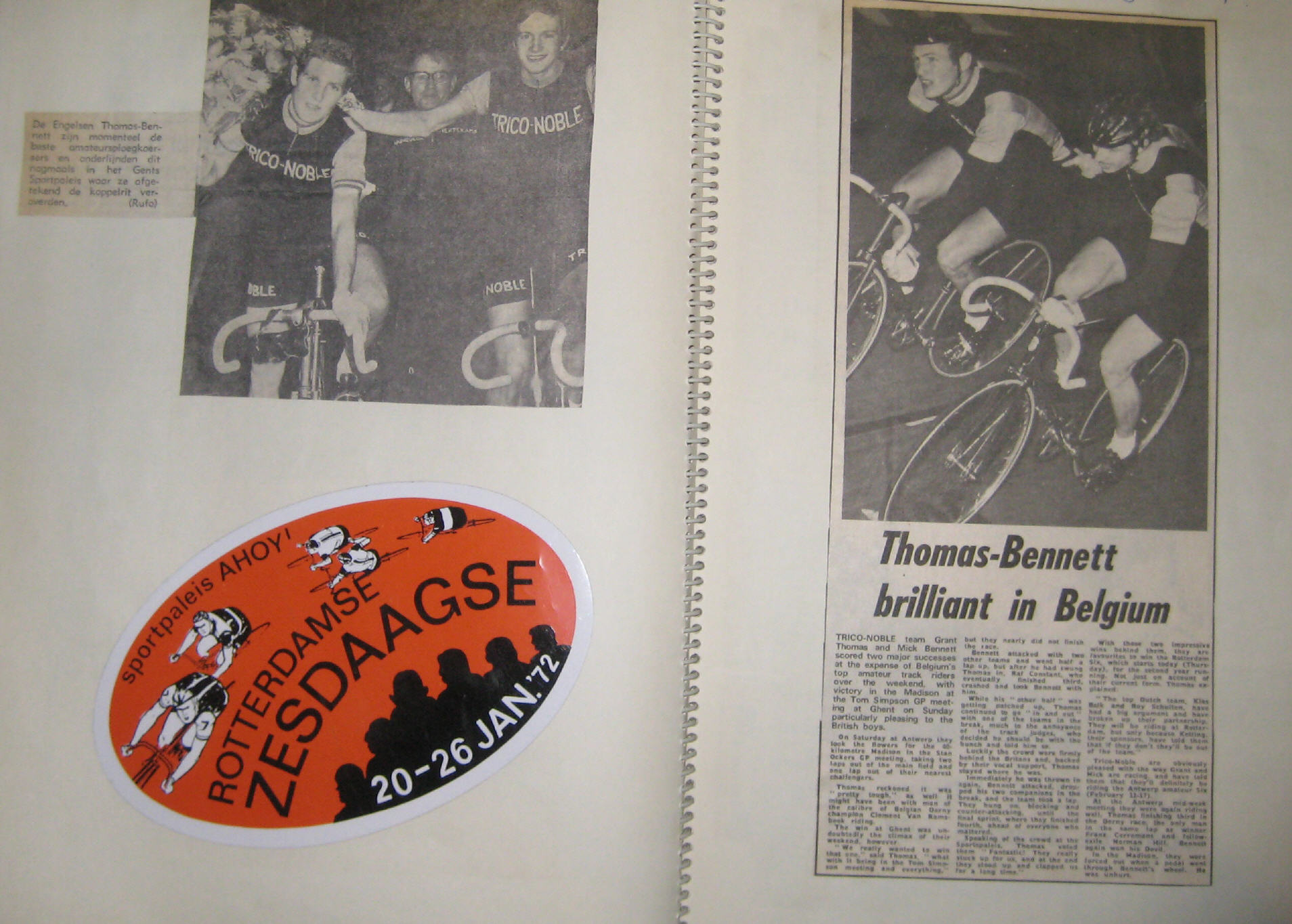

Despite health issues and failing motivation, Grant was able to team up with old pal Mick Bennet on the track, to win the amateur Rotterdam Six Day race.

The pair of them trained specifically for Rotterdam, using the Sixes at Brussels and Gent to hone their track skills after some time away from the boards. “Mick was a class act, whilst I had the staying power, he had the zip.“

* * *

These Days

When Grant decided to quit racing professionally, he went back to college and became qualified in work measurement using a system called PMTS – predetermined motion time systems. “If anyone needs someone qualified in that then let me know!“

Grant is impressed with the ways the pro teams are organised these days, particularly Team Sky. “They’re certainly doing it properly – not like the ANC and McCartney setups.”

Like many people, Grant thinks that Brailsford is taking a lot on with both the professional road team and the Olympic track squads, but believes that he’s a world champion manager. “Some of the pro teams back in my day were a farce; when I was with Falcon, we were going to a race and one of the lads was to get picked up at a service station on the motorway, but they forgot to get him. At the start the manager was asking ‘where’s Keith (Lambert)?“

* * *

Regrets

Grant didn’t want to disappoint his sponsors, or track partner Mick – besides, he had such a passion for the Madison, it was what drove him through the winter yet riding the track after having done 75 races each season was perhaps too much.

Grant realises he should have rested more, and taken his lead from the top guys in Holland at the time, like Hennie Kuiper. “Kuiper wouldn’t ride the track in the winter, he knew his system needed to recover. Also, the twisting that you do as you change in the Madisons exacerbated the problems I had with my legs, I’m sure of that…“

His voice tails off and it’s time for us to go, but it was a privilege to spend an afternoon in the company of a man who went out and did what the others just dreamed about.

Rest in peace Grant.