You students of track cycling out there, which was the year the mighty GB squad won their first team pursuit world title.

Did you say, 2005?

Then you’d be wrong.

The GB team pursuit squad won the event some 30 years earlier, in 1973 but ‘gave away’ the title.

This is the story of one of the team and that huge decision to let a world title go; from the precocious talent that was Rik Evans.

British schoolboy, junior and senior champion – and a world champion whilst still in his teens but lost to the sport with most of his music still within him.

It was a different world back then though; ‘amateur’ meant exactly that and there were no team psychologists or ‘mind mechanics’ to tell you how to keep your ‘inner chimp’ under control. Here’s Rik’s story.

Do you remember your first race, Rik?

“Yes, very clearly.

“It was early May 1966, and – no surprise for that era – a 10 mile time trial.

“I was only 11 years-old; a couple of weeks short of my twelfth birthday, and my time was 30:47, which I was told was ‘very promising’.

“This was on a bike that I’d assembled from bits and pieces I’d found, mainly on bombsites, which were used at that time as unofficial public dumping grounds.

“There were still quite a lot of them around the London area in those days, and there was usually a good selection of wrecked bikes with usable parts on them.

“I became very handy with an adjustable spanner.

“The bike I’d made was basically an old roadster with chunky tyres, steel rims – steel everything, more or less – and I’d managed to scavenge some drop handlebars from somewhere (no handlebar tape though) to make it look more like a racing bike.

“I painted it red the day before the race, which seemed like a good idea.

“The trouble was that the paint wouldn’t dry.

“It wouldn’t even set properly, so it remained tacky and had ‘curtained,’ forming drapes of irregular ripples in various places, particularly along the top tube.

“Anyway, I won my first ever medal that day, for the handicap prize.”

You were very good very quickly – British Schoolboy Road Race Champion in 1969 and Junior Road Race Champion in 1971.

“It’s true that I was good quite quickly, although when I started massed start events in early ’68, I kept getting “dropped and was having a rough time of it to be honest.

“Nevertheless, by the time the ’69 season came along I’d developed a winning mind set.

“I approached races with the attitude that they already ‘belonged’ to me, and that other competitors were just trying their luck in attempting to take what was mine.

“For whatever reasons, that’s how I was then, and I’d done the work to pull it off.

“But I think that so much of success, in this sense, is down to luck; what you’re given.

“Natural aptitude is either there or it isn’t, and equally, the circumstances and environment you find yourself in are whatever they happen to be.

“At that time, the south-east London scene was an ideal environment for any youngster wanting to make it in the bike game.

“The racing scene was ideal: track racing twice a week at Herne Hill, criteriums at Crystal Palace, also twice a week sometimes, and a lot going on in the outer London area as well.

“Most importantly though, were the other riders who were around, and the unpaid individuals who got it all to happen and gave advice.

“I had a very strong cohort of contemporaries around me.

“And they were just that bit older and more developed than I was; many of them national champions: Dave Carter, Alan Upcraft, Steve Heffernan and many more.

“That really helped to motivate me.

“I also had a lot of support and encouragement from established elite riders like Ron Keeble and Reg Barnett, both multiple national champions and Olympians.

“I admired them enormously, and to have their individual attention and practical support was pivotal.

“And along with that, as a 14 year-old I was out doing 200 km training rides with the likes of Tour de France rider, John Clarey, and top pro, Reg Smith.

“So yes, with those circumstances being what they were, and with more than my fair share of natural ability, it would’ve been remiss for me not to do well.”

And you were very successful in junior races on the continent in ’72.

“That was an interesting episode.

“For the first three months or so of that new season in ’72, I had to continue in the junior category until my birthday at the end of May, and I really didn’t want to.

“I didn’t want to wait months to start racing with the seniors, so asked the BCF to grant me a senior licence before I was 18 years-old.

“I was reigning British Junior Road Champion and wasn’t going to be challenged enough in junior races.

“This was a parallel situation to the beginning of the 1970 season when I was reigning schoolboy champion, so a similar scenario.

“On that occasion they did grant me the junior licence early, but this time they refused to play ball.

“This was no good, so I saved up some cash, and as soon as I could, I took myself off to Holland to find something more testing to get my teeth into.

“I’d become de-motivated in England, and getting to Holland gave me a massive boost and took my performance and self-belief to another level.

“I’d call the offices of ‘Cycling Weekly’ magazine once a week to report on my progress, so it was also raising my profile at home – where the selectors were.

“In one race, in the town of Mill at the start of the Olympia Tour, I took off to grab a prime, decided to keep going, and finished nearly a minute in front of the peloton; my first solo win.

“The major thing about that spell in Holland was that it set me up for being selected for the Munich Olympics that year, something I wasn’t expecting.

“I came home with brilliant form, was invited by national coach, Norman Sheil, to join the Olympic squad training sessions, and it went from there.”

Did you ever consider doing the ‘continental thing’?

“For sure, but by the time that opportunity came along – and the opportunity was there – I’d lost the necessary desire to take it up and make it work.

“At the beginning of 1974 I was signed up (along with Mick Bennett) with a team in Holland: Hebro-Flandria.

“This was a top team; very professional and would’ve served well as a fast-track into the Flandria pro team.

“If the trajectory that I was on (or appeared to be on) had have continued, then a decent continental pro contract would’ve been on offer sooner or later.

“I now find it quite intriguing to think that if that had have eventuated, I would’ve been riding, at times, alongside the likes of Freddy Maertens, Roger de Vlaminck, Francesco Moser and even Eddy Merckx himself at the end of his career.

“It didn’t work out that way, though.”

The core of the Wolds team – Hallam/Bennett/Moore a very close knit group, how was it ‘breaking into’ that?

“Well, it didn’t really feel as though I had to break in, as such.

“You could say that Norman Sheil had, effectively, woven me into that close-knit group through my selection for the Munich Olympics.

“I was only 18 at those Games, and in training I was holding my own in their company, I’d blended well with the team, and so it was looking good for me to consolidate my place as I matured from there on.

“It probably is true that I was favoured, but I hope for good reasons.

“We all got on incredibly well; I think there was a synergy between us, and crucially, I’d say that my style of riding lent itself to the nature of that line-up.”

The fateful Worlds ’73 – your thoughts please.

“OK.

“One thing to bear in mind is that back then, any kind of medal at the Worlds or Olympics was a relatively rare occurrence for Britain.

“Years would go by with nothing; no medals at all, so it really was major news whenever it happened.

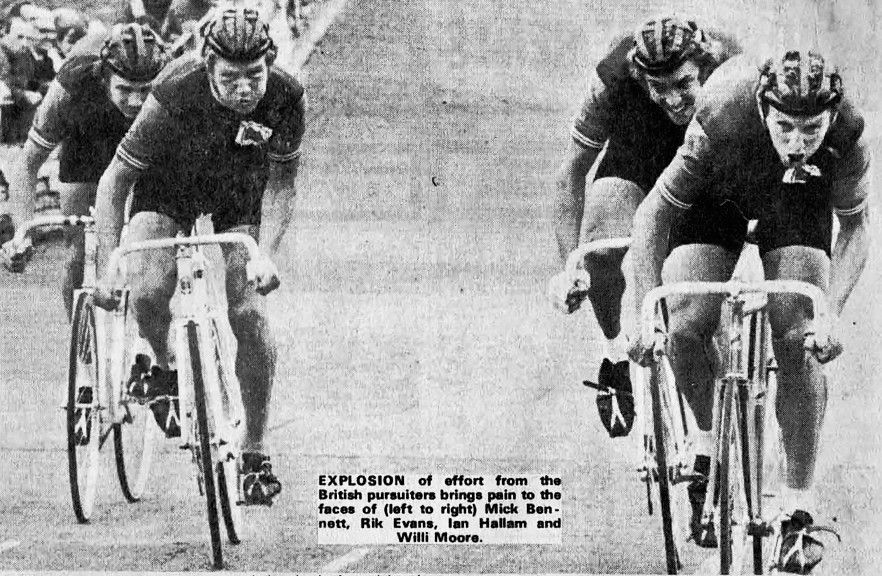

“I can remember the front page of ‘Cycling Weekly’ magazine when the GB team won a solitary bronze in the Munich Olympics in ‘72: “WE WON A MEDAL!” splashed across the front page, with a picture of the team in action.

“That’s how it was.

“And in ’73, when we reached the final of the World Championships in San Sebastian, we were the first GB team to have got that far – it was very big news.

“In the event, we qualified second fastest, caught the Soviet Union in the quarters, won a very hard fought battle with the Dutch in the semis, then faced the Olympic Champions, West Germany in the final.

“The Germans got off to a blistering start, which did throw us a bit.

“They gained a couple of seconds very quickly and from there on continued to make small, incremental gains.

“Approaching the final lap, they’d got over three and a half seconds on us.

“Regretfully, I’d failed to re-join the team after my final turn on the front (team orders were for me to ‘bury’ myself on my last turn and stay in touch if I could – but I couldn’t).

“Having been jettisoned, I was riding along slowly on the inside of the track on the opposite side to where the Germans were as they approached their finishing line.

“The race was all but over, but then there was this terrible metallic clattering sound, accompanied by a collective gasp from several thousand members of the audience.

“An official, taking hold of one of the foam markers on the inside of the track (no one is sure why), had failed to move out of the way quickly enough from the approaching Germans.

“The shoulder of Hans Lutz, the front rider at that point, made contact with said official and the whole team came down, sliding to a halt only a few metres from the finishing line.

“We were, then, declared World Champions, having finished the race when they hadn’t, so, fair enough?

“The West Germans thought not, and lodged a protest.

“As deliberations went on, we rode around in the track centre on our road bikes, all in our own space and immersed in our own thoughts.

“Norman Sheil came around to speak to us one by one to get our views and to confer over the situation, and he was, in effect, suggesting that we refrain from counter-protesting.

“We unanimously agreed to this.

“We’d had every right to counter-protest and could’ve left that stadium as World Champions – according to the rules that is – but we decided against the idea.

“Call me old-fashioned, but my feeling is that a World Championship is about finding the best in the world, and it was quite clear which team was the best here.

“I think that we’d accepted that we were ‘only’ the number two team in the world, but I can only speak for myself on that score.

“It may have been different if the Germans had have stuffed up or transgressed in some way, but they hadn’t.

“They were superb and had ridden a perfect race.

“That evening, as we entered the packed communal dining area, the whole place, including the West German team stood, cheered and applauded us – an incredibly proud moment.

“The reaction at home was mixed.

“To some we were heroes, but there were more than a few who were quite vitriolic in criticising our decision to ‘give away’ those rainbow jerseys, claiming that the Germans wouldn’t have been so sporting, so Corinthian in spirit.

“Possibly so, but if that were the case, all the more reason, I’d say, to have acted as we did.

“I’ve never had any real doubts about the option we took.

“Oh, and to top it all off, as we reflected on things back at our accommodation, one of us noticed that our medals were engraved on the back with “Routes par Equipes” – we’d been given medals for the 100 km team time trial.

“We still have them.

“The Soviet Union won silver in that event, so I guess that they have the team pursuit medals.”

In Part Two Rik continues his story, on racing with top club ’34 Nomads to his slide out of cycling but into depression.