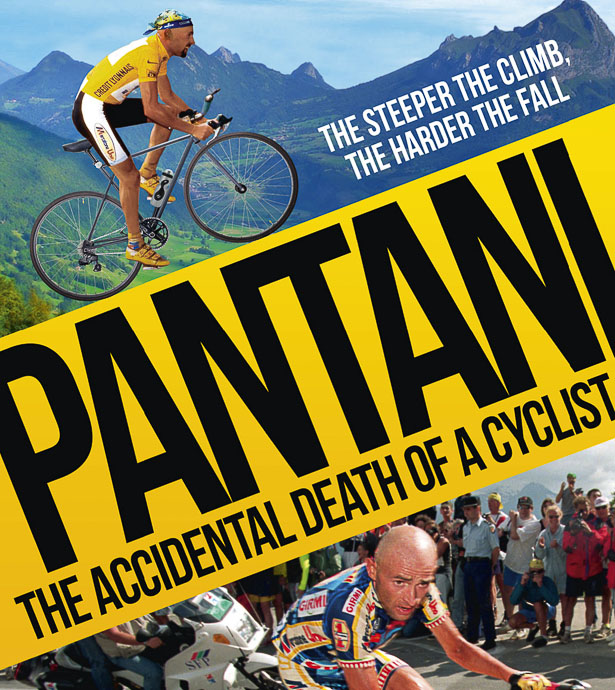

The Pantani, the Accidental Death of a Cyclist film, I guess you have to go and see it?

I was never a huge fan of the man but on his day he was spectacular and impressive.

My amigo John Laporte and I used to drive down to l’Alpe d’Huez every year to see the Tour stage on the mountain; we saw Hampsten win in ’92, Conti in ’94 – and Pantani in ’97.

In ’97 we’d holed up in the Breton bar in the ski village for most of the afternoon and had quaffed maybe a little too much of that Ricard 51 pastis than is advisable.

The roar coming up the hill reminded us we were there to see a bike race and we stumbled out into the daylight to hang over the barrier and await the arrival of les coureurs.

But there was only one coureur, tiny, shaven headed with no casquette to protect him from what was a burning sun – the sweat glistened on the brown skin of his scalp and big beads of sweat dripped from his nose.

Hunched over his machine his eyes were fixed on the road ahead and his mouth hung open to scoop up every bit of oxygen the warm, thin air could yield.

His cadence was high and his speed across the tarmac seemed incredible to us; much faster than we remembered Hampsten and Conti had been in previous years.

He came and went in an instant but his passing left an indelible mark on our memories.

But the question is; ‘what is it real or simply another EPO illusion, just like Lance’s fabled time trial up this same mountain?’

Pantani’s hematocrit levels fluctuated between 40% and 60% from month to month during his professional career.

Sad as his story is, I can see little difference between ‘Lance the evil drug cheat’ and ‘Marco the martyr.’

Except that one is still very much alive and making jokey commercials about how to fix punctures.

Both men faced choices and went down a certain road which no one forced them to – albeit there are the issues of peer and management pressure, not to mention seeing riders who they knew they were superior to, riding at a level which was higher than they were naturally capable of.

There’s no doubt that Pantani was charismatic and determined – in particular his comeback from his horror crash in Milan-Turin in 1995 demands respect.

The shine comes off a little bit however when you remember that his hematocrit was over 60% in that race and it was only the surreptitious intervention of the team doctors that enabled him to pull through – the hospital doctors being baffled by the tests they were running on him and how they were going to regularise his metabolism.

To give you a flavour of what he was ingesting; according to documentation released by Spanish radio network Cadena SER, Pantani – who was allegedly given the code name “PTNI” by Eufemiano Fuentes – with a detailed program in 2003, his last season, including EPO, growth hormone, Insulin, Levothroid and IGF-1.

Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera indicated that he was administered over 40,000 units of EPO, seven doses of growth hormone, thirty doses of anabolic steroids and four doses of hormones used to treat menopause.

Small wonder the hospital doctors couldn’t figure out what was going on in the little man’s body.

Matt Rendell narrates much of the film – but I’m a little puzzled by his ‘Marco the martyr and victim’ stance.

In his well researched book – upon which the film is based – The Death of Marco Pantani, Rendell leaves us in little doubt that the Italian rarely raced ‘clean.’

And Greg Lemond’s pronouncements are hard to fathom; ‘even without the drugs Pantani would have been one of the best’ or words to that effect.

That’s from the ‘they were all at it, so what’s the difference?’ – school of thought to which I used to subscribe.

There’s a ‘but’ or two to that one, though.

Not everyone was ‘at it’ – riders like Eric Caritoux and Charly Mottet achieved great things as men who the peloton – and even the man at the heart of the Festina scandal, Willy Voet – acknowledged were ‘clean.’

And then there’s that word that I never even knew existed until the murky world of 90’s and 00’s kitting was properly exposed – ‘responder.’

This refers to the fact that if you have a naturally low hematocrit level then you’ll gain much more advantage from taking EPO than someone who has a naturally high hematocrit.

With a hematocrit down at 40% then Pantani would make huge gains from taking EPO – so forget the ‘level playing field’ debate.

There are some real gems of cameo performances in the movie – Tricky Dicky Virenque cries to order; Oscar Camenzind tells us that ‘rules must be obeyed’ meanwhile Bjarne Riis and Luc Leblanc give it max righteous indignation.

I did chuckle; and I had to smile as Erik Zabel rides tempo for Ulrich up a mountain pass – how did we believe our eyes, back then?

But back to Pantani’s Accidental Death of a Cyclist – the seed of his long descent into Hell began when he was expelled from the 1999 Giro because of his hematocrit level exceeding 50%.

There’s little doubt in my mind that there was more to that incident than meets the eye; the story about there being big bets laid on the race by the Mafia – and not for Pantani to win – is one I’ve heard from several usually reliable sources.

It’s here the big difference between Lance and Marco is revealed; the Teflon Texan would have brazened, blustered and law suited his way through it and been back for le Tour and probably won.

But the much more sensitive Pantani didn’t have the head or heart for the ‘Texas way’ of doing things and the shame of exposure began to eat at him like a cancer.

He was never the same again – even his subsequent Tour stage wins meant little to him; Armstrong’s precisely aimed barbs about gifting him the Ventoux stage and Pantani’s appearance were right on target, fatally wounding the little Italian’s pride.

For all of the EPO – and God only knows what else – Pantani pumped into his frail body and the fact that much of what he achieved was pure sham, he gave so many people so much joy and if they wish to believe he’s a martyr then that’s their choice.

And listening to his poor mother and father surely touches even the most callous heart.

For me it’s all just very sad, not just Pantani’s story – but the performances by Leblanc, Camenzind, Riis and Virenque and that era of mega lies we lived through.

So if you’re Bradley Wiggins or Chris Froome, no matter how annoying it may be, when ‘too good to be true’ performances get questioned – is it any wonder after all of that?

That said, let’s hope that Marco Pantani is resting in peace – his final years were a torment and it’s impossible to say that the man didn’t pay the price for the mistakes he made.