We were sad to hear the news of the passing of one of Australia’s top track and road men, Dean Woods, on March the 3rd at the age of 55.

He’ll be missed by everybody whose lives he touched. Admired, loved and respected by all. A truly iconic legend.

A service to celebrate Dean’s life will be held at the Wangaratta Performing Arts & Convention Centre, 33-37 Ford Street, Wangaratta at 11.00am on Tuesday, 15 March, 2022 followed by private burial.

We spoke to Dean back in 2015 and thought it would be a nice tribute to run the interview again.

* * *

This article was first published 9th June 2015

When we asked Aussie pursuit star of the 1980’s and 90’s, Dean Woods if we had his palmarès correct; he got back to us with his own list.

It rather speaks for itself …

- Olympic Games Gold Medallist at Los Angeles 1984.

- Olympic Silver Medallist at Seoul 1988.

- Olympic Bronze Medallist at Seoul 1988.

- Olympic Bronze Medallist at Atlanta 1996.

- 3 times World Cycling Champion ’83, ’84, ’96.

- 3 times Commonwealth Games Champion ’86 (double), ’94.

- Australian Sporting Hall of Fame Member – 2000.

- Recipient of Order of Australia Medal – Services To Cycling.

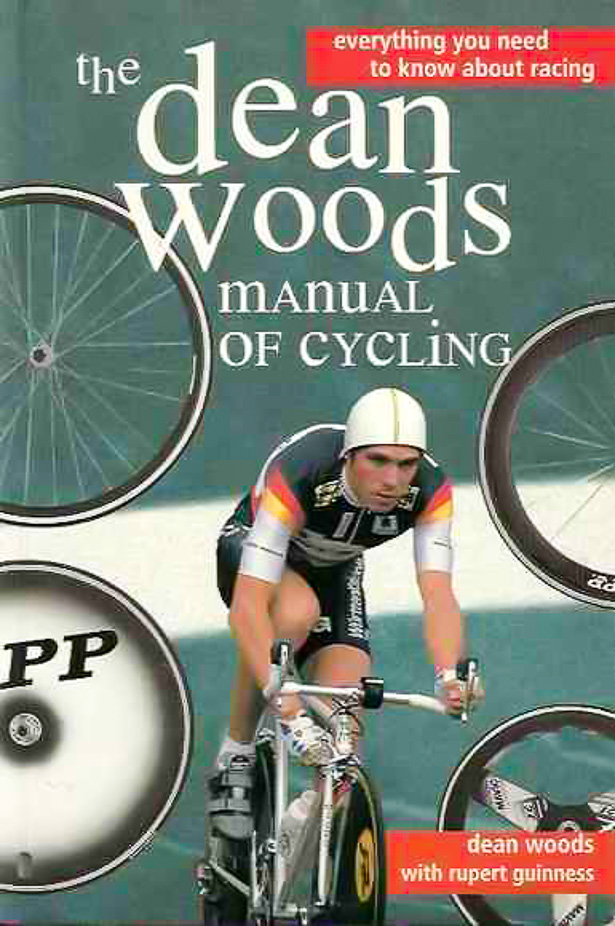

- Co-author of “The Dean Woods Manual of Cycling”.

- Melbourne to Warrnambool Road Race Winner.

- Melbourne to Warrnambool Record Holder 1990 (Time 5hrs, 12min – 262km)

- Ranked top 4 In the World for Individual Pursuit (From 1983 to 1992)

- Winner of 20 National Championships.

- Winner of 15 State Championships.

- 1 World Record.

- 4 National Records.

- French Amateur team ASCM Toulon 1986/7

- Professional Road teams;

- Team Stuttgart ’89/90

- Team Telekom ’91

- Southern Suns ’92

- Jayco ’93.

Without further ado let’s hear what one of the finest pursuit riders of his generation had to say to VeloVeritas, recently …

How did you get into cycling, Dean?

“If I look back through my family history whilst there have been a couple of family connections within the sport of cycling really there’s no outside influence or promotion to entice me to begin, so you could say I fell into the sport at 10 years-of-age.

“My older brother started to race and I would go along to watch but very quickly grew tired of just watching – then the chance to try the sport presented itself and I borrowed a club bike for some training rides and to try racing, my first race being on 03/07/1976.

“To say I was an ‘outdoor kid’ is probably an understatement and I remember my first bike at around the age of four or five making the rest of the world my playground.

“Back then learning to ride a bike as a way of getting to school was normal; it was either that or walk – which I wasn’t a fan of.”

Which riders were your inspiration as a young cyclist?

“The earliest inspiration was watching a local Athletic Carnival on the Australia Day long weekend which incorporated foot running, wood chopping and of course cycling.

“This was a typical format and in many senses was the backbone of Australian sporting culture, post war, through the country and many communities would have their own event, many of which do not exist nowadays but certainly for a young kid with an interest in sport it was bigger than Christmas.

“Growing up in a cycling environment, Euro cycling information was always somewhat slower and the national publication, ‘Australian Cycling’ by the late John Drummond was the magazine, our bible, for those who has a thirst for knowledge – but it wasn’t until my first view of the UK magazine ‘International Cycle Sport’ with full colour images of the heroes of the day competing in the races we had only heard about.

“Eddy Merckx was the inspiration, you would see images of him in Yellow, Pink or splattered in mud riding the classics and was always photographed taking charge of the race when it counted.

“I remember hearing a story as a young boy that at the beginning of every season, Eddy would remove his toe straps and ride the first month on a small fixed gear to get the pedalling fluency back in his legs after his break, so you can guess who mirrored this exactly.”

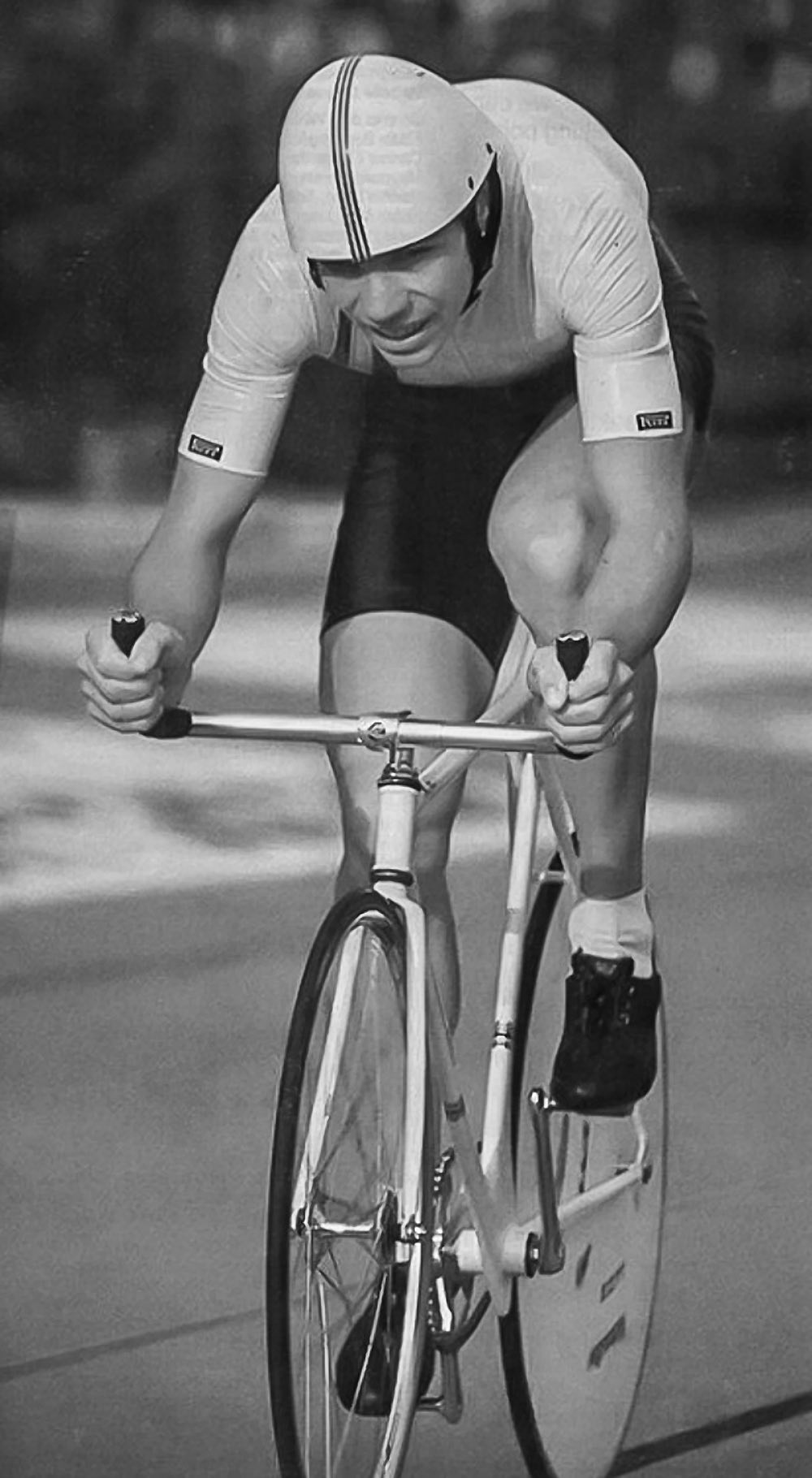

Your rise was rapid; an Olympic gold whilst still riding as a junior.

“If I reflect back there were a few thing happening before the ‘84 Olympics that I can honestly say they were definitely preparing me for this opportunity without realising it.

“Previously I was national champion as a 16 year-old on the road and track so a level of natural ability was evident but no obvious indication of what level it may reach with the correct guidance.

“At the age of around 15 I started to experiment – yes that’s right, experiment – with timing myself around a 60km circuit where there would be certain sections that I would sprint or put the hammer down for a few km’s but more of this later.

“Beginning my working life as an apprentice Plumber at the age of 15 ½ was a massive shock to the system, from sitting in a classroom at school for six hours and training, to working a laborious job for eight hours plus and trying to train, were worlds apart.

“I had won the Junior World Pursuit Championship and was second in the Points Race in New Zealand the year before in ‘83 so I guess I had a few indicators that I had some qualities to do something in the sport and up until this point I never had a coach to assist with development.

“Actually I didn’t have access to a coach until the National Coach Charlie Walsh contacted me just prior to Christmas ‘83 asking what my intentions with cycling were and what amount of training I was doing as he knew I was working full time as well.

“My times were comparable to what the seniors were riding so it made sense for Charlie to enquire what my intentions were in the short term as the Los Angeles Olympics were only six months away; realistically, I was thinking at maybe Seoul four years later but I was beginning to realise that there was an opportunity looming closer than that.

“When I was selected in the national team for the Olympic Games in Los Angeles, I was still 17 years-old and clarification had to be made to the Australian Olympic Committee if there was an age limit for selection in the cycling team as I was still licensed as a junior cyclist.

“This was new ground for everyone and there was a 12 month period where many things were changing in a hurry.”

The LA Olympics ’84 – a lot of pressure for a young man?

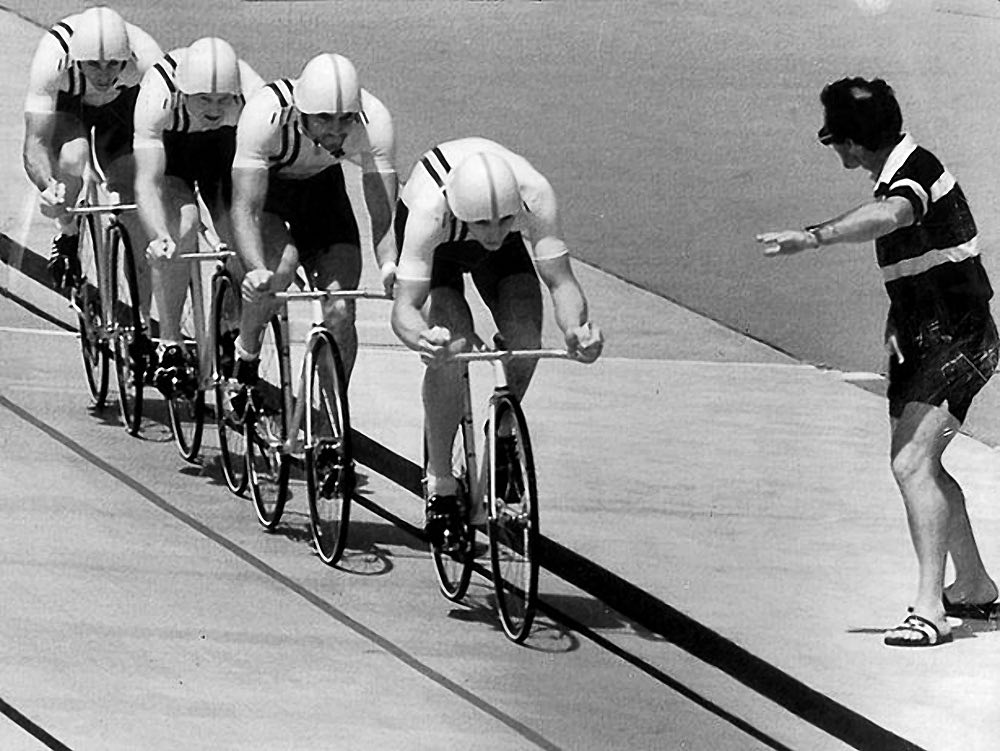

“I can honestly say that if the team was made up of 18 to 20 year-olds the result would have been dramatically different; it was my first exposure to a team environment and what an environment it was.

“Even though there were different ages, personalities and sometimes a little friction, everyone NEVER forgot why we were all there, to do the best as we could as individuals and as a team so as a young bloke I was experiencing the cold hard fact of cycling, “it’s bloody hard!”

“The team event I always had the reassurance of experience from the other guys to feed off but the individual pursuit was a different game; after all I was just the young punk on the team that had all of a sudden appeared on the scene.

“Could I do this, am I good enough to do this?, was going through my head however I was not going to die wondering and always had the conclusion that I had nothing to lose which as basic as it is seemed worked quite well.

“We all have an experience in our lives that is a game changer and this time was certainly mine, I was fortunate that mine was early in my life which allowed me to not only grew as an athlete but as a person as well and this life experience I still use every day.

“Just to put the word ‘pressure’ into perspective a quote from one of Australia’s best test cricketers and fighter pilot during World War Two, Keith Miller; he was asked this question by a young journalist during a post war tour of England on how he handles the pressure of international test cricket.

“His swift reply was “son – pressure is a Messerschmitt up your arse” that certainly puts pressure into perspective for me!”

What about those fabulous bikes the USA team rode in LA – did that faze you at all?

“Some of the prototypes the Americans were developing were being trialled at the junior world championships in New Zealand the year before so they weren’t a huge surprise.

“However it was not clear whether they would be allowed at the games in LA or not as the usual protocol was to present any equipment developments or changes at the world championships the previous year and either passed or denied by the UCI.

“But who would be so daft to think that the UCI would stick to their own process!

“At the European championships in Brno leading up to the LA Olympics a few countries had disc wheels, Swiss, Italians etc. but word was circulating that they still has not been passed by the UCI and would be deemed illegal in LA, right?

“Totally wrong!

“Not that we had any funds for any equipment like disc wheels anyway, so we turned up at the St. Dominguez and quickly realised that it was an equipment free-for-all.

“After all, we should have realised that when US Cycling spend $250K on a bike with a total budget of around $5m to prepare for the games there was no way they were going to spend all this money on equipment for it not to be used. All aluminium frames made from leftovers from the space program, integrated handlebars and stem – the best of the best.

“We, on the other hand had a budget of around $25k for both the track and road program to support four months racing and training in Europe so thanks to a strong exchange rate of the Australian dollar the money was able to go a bit further; track gear was supplied but road bikes were our own responsibility.

“Our track bikes crafted by Geoff Scott in Sydney, manufactured out of his garage with a value at the time in raw material of less than $500 with team sponsor Malvern Star, made famous by Sir Hubert Oppermann, plastered all over the frame so our equipment was as Aussie as you could get. The only things missing was Kangaroo skin shoes and a meat pie for a helmet.

“The most intriguing thing was that we still won (the most profound experience possible) it was more of ‘what we didn’t have’ because we certainly didn’t have a lot but we still managed to keep it all together and never lost the focus on ‘giving ourselves every chance to do the best that we could.’

“And just to round things off, I found this line while doing some research for this article which explains a bit more the magnitude of the victory; “Altogether the US won a record 9 medals in cycling events. After the Games it was revealed 1/3 of the US team received blood transfusions before the event, which was still one year before it was banned by the IOC.”

“Just as long as blood doping was eventually banned sort of makes it ok?

“What a load of bollocks!”

On the subject of bikes; you rode through the transition from steel to monocoque and spokes to discs – can you tell us a little about that please?

“During the 80’s and 90’s there was a high level of development in bikes which form most of what we all see today.

“The Moscow Olympics in 1980 saw the first appearance of low profile bikes with Russia and East Germany being among the first. It was a crude version with the handle bars being welded directly to the front of the fork crown which is how Lothar Thoms from DDR won the kilo at the games that year.

“The LA games saw the introduction of alloy to frames and disc wheels though they was still a few years off from being used commercially due to the expense and 88’-89’ saw the emergence of the aero bars from the triathlon scene and at first were seen as just another gimmick, that was until Greg Lemond cleaned the floor with Laurent Fignon by a lousy 8 seconds on the last day of the 89’ TDF.

“Front wheel size ranges from 27” to 24”, then 26” and back to 27” so I suspect there was more focus on sales rather than testing of equipment during this time, the early 90’s saw the wider use of aluminium material for frames and then a gradual development of carbon fibre.

“The first years of carbon was very expensive and was only used on the top end bikes, now even the basics are carbon.

“I see bikes for around the $1k mark that are far better than the pros were using up until the mid-90’s.”

What gears did you ride back then and what were your best times – what do you think of the current ‘mega’ gears and times?

“All track events have gone through major changes in recent times and my take on this I will get back to; during my earlier years I was experimenting with high cadence under load although I had no idea what I was doing at the time, I was probably more interested in getting the training over with as soon as I could as training in the dark with candle power for lights was not a favourite of mine.

“After doing this two or three days a week I was noticing an improvement in my times around this circuit, the short hills I would punch up without any distress at all. What I was doing was laying the foundation for an efficient oxygen system and developing a powerful anaerobic capacity in my mid-teens required to ride four kilometres at a world standard without knowing it at the time.

“My gearing was generally between 88.2 and 90.6 inches with 170mm crank length, dependent on conditions, with the ability to ride consistent times for four or five races in the competition; at the time the world record was a 4:37 with most competitions still being held outdoors – so weather conditions had to be factored into gearing selection.

“So this is where the dynamics of pursuiting have changed, the IP now has two rides at best, all major competitions are held indoors so the environmental element is removed.

“I recall distinctly at a few world championships conducted outdoors with a 20km/h wind down the straight so you had a distinct advantage if you finished with a tailwind, so windy conditions with four rides over two days on 108 inch gear – I’d like to see that!

“Today everything is built around speed which is a good thing and these changes contribute largely to the sensational performances we see today, even the current world record held by Jack Bobridge will be broken as continual improvement is inevitable.”

Aussie coach Charlie Walsh – are the stories of a tough regime with 10 hour ‘fat burning’ rides true or exaggerated?

“Absolutely true, with a hint of exaggeration thrown in; at certain times of the year our training would be based around building a foundation of endurance training.

“Including yes, extended time on the bike to prepare for the following phases of training that was planned in the following months – each phase or training block was critical to be able to adapt to the next level of intensity training.

“So if one phase of training was missed through illness or performed at a substandard level, then you were always behind of what was required which in turn lead to over-stressing the body trying to cope with the workload – leading to over-training and potentially other health problems.

“It’s not too difficult to realise the importance of the different training phases required to develop to the next training stage.

“I have always viewed the training structure to be absolutely demanding without question but let’s face it, we were trying to be the best in the world not the best in the club so generally the training will be harder – I have often wondered what else would anyone expect at this level?

“The alternative would have been a lot harder – stay at home!

“This was during the time when if you wanted a training program you had to test your own theories not just print one off the internet, so there was a massive element of ‘trial and error’.

“I hear critics of Charlie’s whether they be former riders or coaches of today stating that the training was wrong, too hard etc. but a lot information that is readily available to everyone was developed during this time.

“Back then Charlie had a blank piece of paper to work from, today we have a document filled with information on training that everyone has access to; I know which option is easier.”

Edinburgh ’86; you and the Australian team were in great form.

“The Games in Edinburgh were six weeks before the world championships in Colorado Springs so was viewed as an important competition for a couple of reasons, the prestige of the Commonwealth Games of course but also a test event to gauge condition and performance before arriving in America.

“The whole team was firing; Martin Vinnecomb won the Kilo, Gary Niewand the sprint, Wayne McCarney the scratch with me second, we won the team pursuit and I won the individual pursuit.

“This competition was an interesting one; apart from persistent rain during the week of the Games the emergence of Colin Sturgess as a 17 year-old and seen as a big talent for the future – and Chris Boardman with Rob Muzio making up the three of the English competitors.

“I rode against Chris in the quarter finals and caught him before half way of the 16 lap event and beat Colin in the final also catching him before the final kilometre so it gave me a clear indication that my training was going well; Colin would gain his revenge three years later at the world championships in Lyon.

“And Chris…? Nothing to add there, his stellar career speaks volumes.”

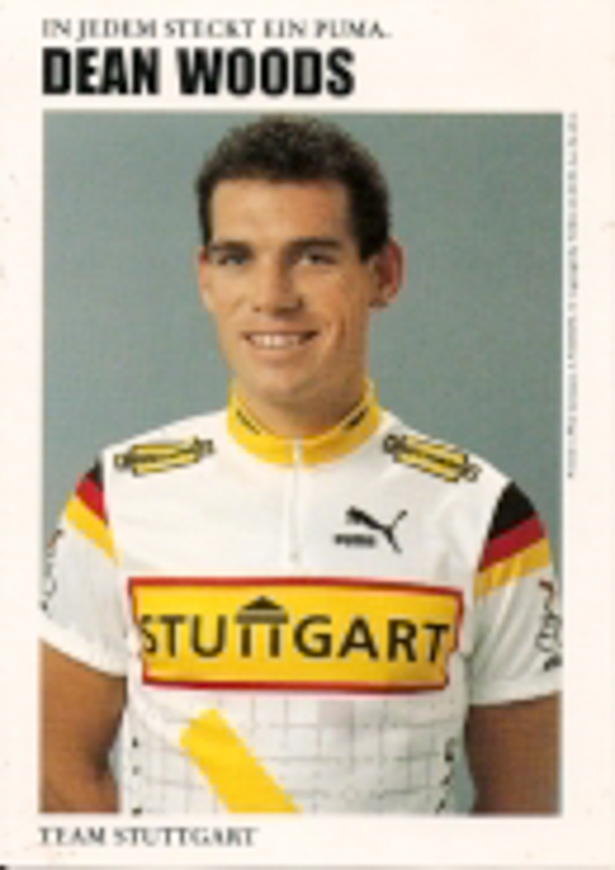

Tell us about turning pro with Stuttgart and the transformation to Deutsche Telekom.

“After the Seoul Olympics in 1988 I was back in Australia riding the Commonwealth Bank Classic when I was talking to a few of the riders on the German team that were riding the event and were talking about a new pro team being organised for the next season.

“I had initially planned to return to France to ride a full season with ASCM Toulon that was influenced by renowned DS Micky Weigant who was instrumental in the early careers of the newly established English-speaking riders, Phil Anderson, Alan Peiper, Stephen Roche just to name a few, through the prestigious Parisian amateur club ACBB.

“Two seasons previous I had ridden the early part of the season from February with Toulon under the guidance of Micky – he always had his eye out for talent that he could introduce to the pro teams as potential neo-pros, for which he would receive a retainer if the riders were accepted.

“It was at a time when Phil and Alan were just seeing the acceptance of the English speaking professional and making their mark in the pro ranks and Micky was looking for the next Aussie to follow the path.

“However, I received a call from the new German team DS Hennie Kuiper just after the conclusion of the bank race to ask if I was interested in turning professional for the 89’ season with this new team.

“I was torn between the two options of returning to France and if all was well I could have the option of turning pro for maybe Peugeot towards the end of the year or taking the “nothing to lose” approach and jump in at the deep end and accept the Team Stuttgart option.

“So with the help of UK based ex-pat Aussie, Ron Webb, a contract was inked on Friday 2st December 1988 to ride for the new German Team – Stuttgart.

“The first two years were a struggle but I managed to achieve some reasonable results that would see my contract extended for another year when the team sponsor changed to Telekom – which was the early formation of T-Mobile.

“My third year was better but still tough getting used to the long days of racing, I found it amazing how I could race hard for 220km and hold my own but that last 40km was like another race and I really needed at least another season to adapt – but the new management taking over in the fourth year weren’t interested in the future, they were interested in now.

“Walter Godefroot was taking over as DS from Hennie for the 1992 season and no new contracts were to be signed by the current management so we were told that all contracts would be renewed after the Vuelta which we were riding in, back them the race was conducted on late April/ early May.

“After the Vuelta, management then said we would have to wait until after the Tour de France – which the team was not ranked high enough to start but came close to a wild card entry – we were assured all would be organised after then.

“Eventually September had arrived and the reality set in that they had no intention of renewing the majority of our contracts, as the team was registered in Germany the bulk of the riders must be from the country of registration so the rest of the positions were filled by Belgium riders and personnel.

“Maybe this was some kind of leftover from the 40’s but I was told a few years later that this was normal practice to intentionally leave riders in limbo as late as possible in the year, when I asked why would they would want to do that, this the answer was quite simple.

““It looks bad for the new DS if you go to another team and perform well”, thanks Walter!”

Why go back to Australia when you did?

“I remained in Germany for the winter of 91’-92’ to ride another Six Day season contemplating what might be next, as choices were a bit thin, I managed to score a place with South African outfit Southern Suns sponsored by a chain of hotels that were riding for six months in Germany.

“In between this I was in contact with Shane Sutton who suggested that I “get my arse over to the UK” to jump in with him, Keith Lambert and the Raleigh-Banana Boys for a series of races in England and Ireland, then back to Germany for the rest of the year.

“I stayed another winter for the Six Day season when I made the decision to pack up and return to Australia as there was little chance of returning to a road team what would have made it financially viable to stay another season.

“Just before I left Germany I receive word that there was a new domestic pro team being formed in Australia backed by Orica-GreenEDGE owner Gerry Ryan, which began an incredible partnership between Gerry and Australian Cycling and in many ways without this partnership it would have left Aussie cycling in a bad place.

“I took up the offer to ride for Team Jayco for the ‘93 season and kicked off the pro team concept in Australia, sure there has been teams around before in Australia but this was where real team racing philosophy started to take hold.

“This arrangement still allowed me to ride the winter boards in Europe for a few more seasons.”

No Commonwealth Games in ’90 or Olympics in ’92?

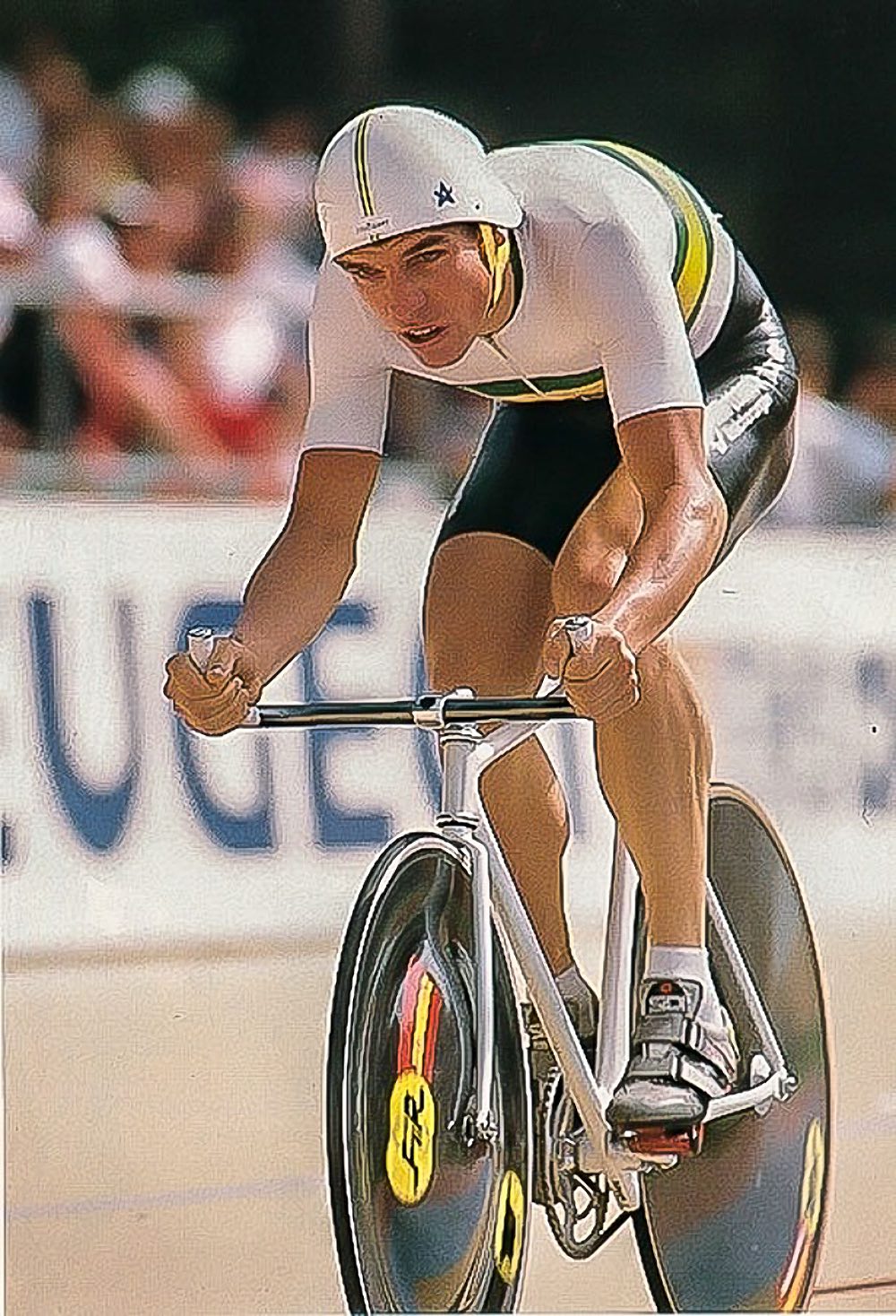

“When I turned pro for the ‘89 season it made me ineligible to compete in any further Olympic or Commonwealth Games but sport was changing and after the ‘92 Barcelona Games, competition was deemed “open” to all athletes whether amateur or professional.

“So during the year riding with Jayco in Australia I decided to return to the track to qualify for the Commonwealth games in Victoria, Canada the following year.”

Back for the Commonwealth Games in ’94 and Olympics in ’96.

“The Australian championships and selection races were in Adelaide in March ‘94 so off the back of another 6 day season I had limited time to prepare for the championships in Adelaide but still enough to do what was necessary.

“I was 27 years-old old at this point, not over the hill by a long shot, but was surprised at the reception I go at the championships from people that I had known for many years and were good friends.

“I honestly think that their perception of me trying to get back into the National track was that I was wasting my time; ‘too old and too long off the track’ one state manager said with a smirk on his face.

“The first event of the competition was the 20km scratch race, Aitken, O’Grady, O’Shannesy and the McGee brothers made it a difficult race to be competitive in but as always I had nothing to lose so a decent finish would test my level of competitiveness.

“The race was full tilt from the gun and it didn’t take long to begin sorting the field out; towards the end O’Grady and I took a lap on the field which we caught with less than 10 laps to go; I never had the legs to beat Stuey in a sprint by a long shot but was more than happy with the silver medal.

“What an instant turnaround from the people who less than one hour before were shaking their heads at the thought of me trying to make the track team again, they were shaking my hand before I had the chance to warm down – but there was a bigger hurdle to jump, make the final of the IP to ensure team selection.

“Just when Graeme O’Bree was riding his ‘washing machine on wheels’, resident frame builder and technician for the Australian Institute of Sport Brian Hayes was playing around with this own version of the bike I and was asked by Brian if I wanted to try it out, the same was offered to Brett Aitken but he refused and preferred to ride the bike he was more use to.

“The bike was so fresh there was no time to even paint it so after only a couple of rides I was back in the track riding the Individual pursuit event once again.

“I made the final against home crowd favourite Brett Aitken, with Brett breaking the Australian record in the semi-final, so with an O’Bree lookalike bike, no paint and 104 inch gear I won the Individual Pursuit National Championship in a new Australian record and also selection on the Commonwealth games team.”

The Six Days – you could have ridden them for years to come, why not?

“My first Six Day season was in ‘89 and my last in ‘96 and certainly there was more opportunity to ride for many years to come as I stopped racing internationally at the age of 30 but to put it bluntly I’d had enough and realised that I had other opportunities outside cycling.

“I use to ask riders the same thing; I remember talking to Arjan Jagt, Dutch bronze medallist in the amateur road race in Colorado Springs ’86.

“I asked him if he was riding again with Super Confex the following year, he replied “no man, I’m moving the US as I have been accepted as a commercial pilot with one of the American airlines”, he turned pro in ‘88 and finished in ‘91 but had greater interests outside the sport and stopped cycling in ‘91 at aged 25 – for the first time I was thinking what my options were outside cycling when my time was up.

“He is now a captain for KLM airways, a man of many talents.

“Before Atlanta I had made the decision not to aim for Sydney Olympics and to concentrate on a business venture I had started with a business partner a few years previous.”

We’ve concentrated on the track but you had some nice road results – which ones give you most satisfaction?

“I always found it amusing when I used to get labelled as a ‘trackie’ as I have spent more time on a road bike, riding road races and have been privileged to have experienced the various disciplines at the highest level of cycling – World Championships, Olympic Games, Pro Road Racing and Six Days with and against the biggest names of the sport; but road racing was always the most thrilling, with two Vuelta’s, Roubaix, Flanders and everything else in between.

“Riding a major classic is a lot like riding a track race with brakes it’s so hectic.

“The most thrilling experience on the track is riding a Six Day on a 160m track, that experience is something worth paying for.”

You were only 30 when you quit – very young …

“It seemed to me that the longer you rode pro into your 30’s the harder it was to make the transition to a regular life and I have seen many examples of that.

“The transition takes around three years to feel comfortable doing something else – cycling had dominated my life for 20 years.

“I was told about that three year rule by Danish world champion Hans Henrik Oersted – he had struggled with the same thing when he retired from cycling and I can say; he was dead on the money with this one.

“I married my wife Meagan in ‘94 and spent the next three years married to a team, so after Atlanta the timing was right to change direction.

“Physically I could have raced longer but psychologically I knew this was the right time to dismount!”

I remember you had a bike shop – what do you do nowadays?

“I began a wholesale company at first which was relatively easy to establish as my network of people in the cycling industry was massive, so making connections and deals was not a problem but I wasn’t satisfied with the dynamics of the way business was conducted.

“We were increasingly interested by the way the Internet was changing the American business landscape with the on line sales model, so after a short discussion we sourced information on web site construction and within a few months we has a web site up and running and were selling our products on line – this was 1997.

“We initially only wanted to be an on line store but received very little support from other suppliers as their excuse was “you don’t have a shop front”, easy fixed, let’s open a shop front as we have to house our stock anyhow.

“We were the first company in the Australian bicycle industry to use e-commerce as a business model for retailing, which caused an absolute uproar with the established wholesale system; we were even banned from advertising in one of the larger national bicycle mags after a few of the publication’s larger advertising accounts threatened to pull their ads if they continued with ours.

“It wasn’t long before the companies that were the most vocal about us selling on-line had their own web sites up and running, strange that!

“The company was purchased in 2008.

“Currently I work for one of Australia’s largest advertising companies and am studying for a degree in business management.”

Any regrets?

“A few, but I’ll leave them for another time.”

* * *

Condolences to Dean’s family and friends from all of us here at VeloVeritas.

Dean Woods, Rest in Peace.