One of VeloVeritas’ functions it seems is unlocking the memories of those stalwarts – like our own mentor and soothsayer, Viktor and indeed, our editor Martin – who beat a path in the 70’s and 80’s to the legendary Mrs. Deene’s boarding house in Gent (and later in Zomergem) to show those Belgies how it should be done. The latest epistle which came our way was from Norman Gower – and mentions of the late, great Grant Thomas did his chances of being published no harm whatsoever.

Over to you, Norman…

* * *

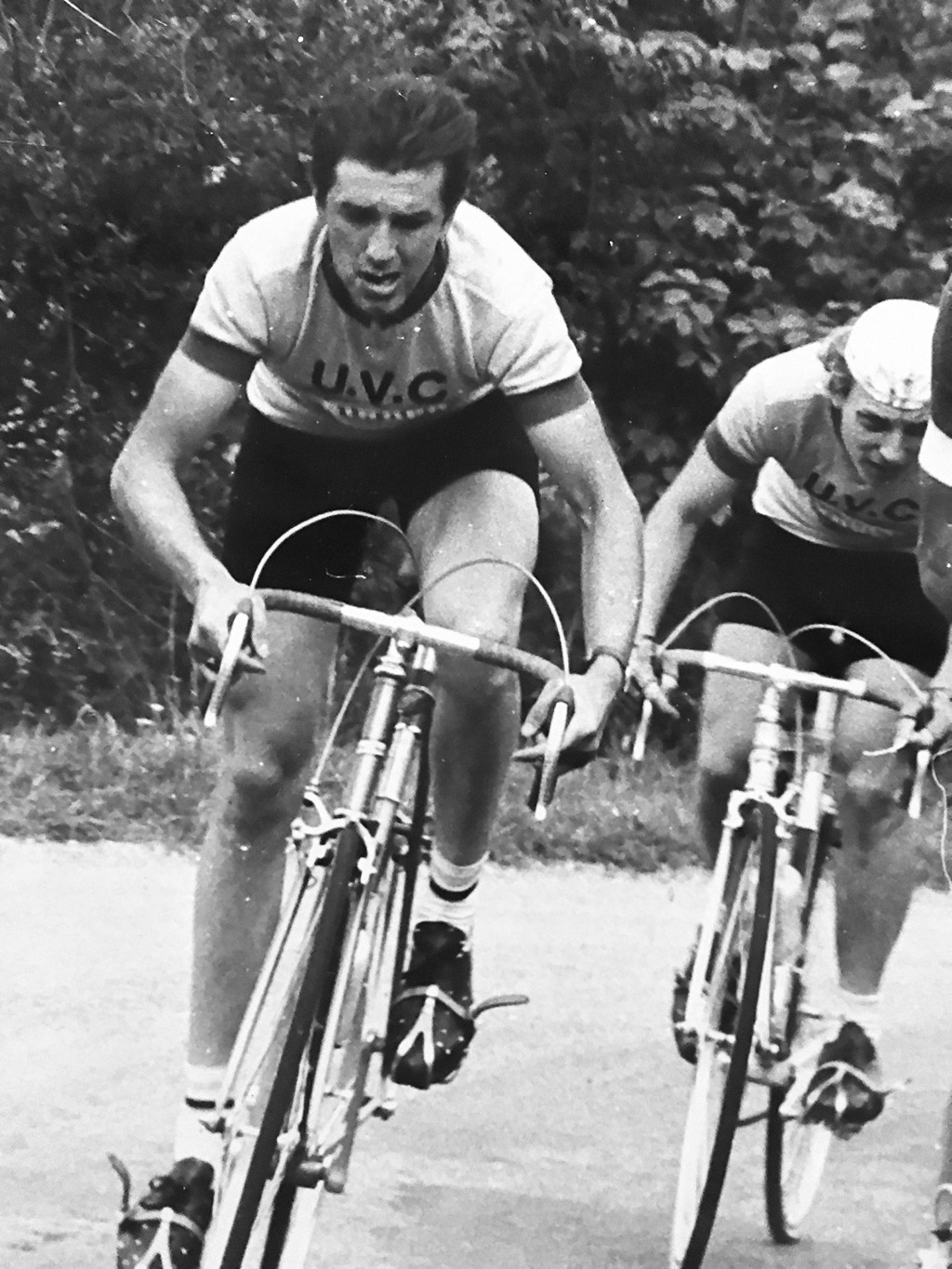

Our Time in Belgium

By Norman Gower

It must have been soon after Easter 1972 when Ron Pannell and I decided to go to Belgium.

Ron was fed up with working, as was I so we loaded our bikes onto the roof of my Escort and set off for Dover.

I should say at this point that Ron was a tough ex-pro who’d had a lot of experience riding pro races in Belgium, France and Britain under the colours of Rory O’Brien, EG Bates and the various incarnations of the Sun Team before being re-instated, whilst I was just one of those who made up the numbers, was hopelessly out of their depth and tried to make up with enthusiasm what they lacked in ability.

I had ridden a few races in Belgium and knew what to expect so was under no illusions but it was preferable to sitting all summer in a drawing office.

Mrs Deene rented us a downstairs flat in, I think, Engelenstraat around the corner from her house in St. Michaelsstraat where we settled in and tried to make ourselves comfortable, but the weather that year was awful, wet and cold.

Our flat had a stove so we bought coal and lit this thing but it seemed like George Deene hadn’t had the chimney swept in years and most of the smoke was exhausted into the living room which doubled up as my bedroom.

It was a relief to get out into the rain to go training.

It seemed always to be cold or raining or both but we went out always with rain jackets in the jersey pocket and nearly always wore them at some time on our rides.

Ron would grind along on something like 52×16 so I did the same and although it was often tough I think it did me good.

We bought Wielersport, some of which I could understand, Flemish having a lot in common with German, where we picked out races which I hoped wouldn’t be too tough.

Some chance, easy races were as rare as rocking-horse shit, so we rode and Ron generally went well in them and even I occasionally managed to get to the finish usually in about 25th place. This was really meaningless since prize money only went down to 20th and anyone without a chance wouldn’t bother to finish.

I seem to remember Tuesday races were of a higher standard with prize money down to 30th or more. Needless to say, I didn’t do anything there either.

One day Ron and I were I asked to make up the numbers in an unofficial GB team to ride in two supporting criteriums to the pro Omloop van Ost Vlaandern at Everghem.

The pros did a few laps on our small circuit before heading out into the countryside.

Then the first of our races took place; star of our team was the late Grant Thomas of whom I was in great awe. He was supported by Terry Carroll who’d also spent a long time living and racing in Belgium and the Netherlands and a few more whose names I’m sorry to say I can no longer remember.

Our race was fairly short and Grant duly won.

Then the pros reappeared, did a few more laps of the small circuit before heading off once more into the wilds of East Flanders.

We were then called to the line again for our second race where Grant successfully defended his overall lead and I was able to bask in some reflected glory without having done anything to deserve it, having me in the team was worse than scraping the barrel.

Finally the pro race returned, won by Willi Vanneste on his own.

Sometime after this the race which Hugh Rainbird mentioned took place around the port of Ghent.

It was raining, as normal, which made the crossing of the railway lines running diagonally into warehouses a bit more hazardous than usual and it seemed that every lap there was the familiar sound of bikes and bodies coming to grief on the wet cobbles until inevitably, it was my turn and the next I knew I was bouncing along on the floor of a police van being transported to Klinik Vercauteren-Drubbel which is – or was – near the Dampoort in Ghent.

They stitched the cut on my head, in those days crash hats were rudimentary strips of padded leather with merely symbolic protection, and strapped me into a sort of bridle, that could have been worn by a horse, for my broken collar-bone after trying to reduce the fracture. This was not too successful as I’ve still got a large lump where it was broken.

I was put into the ‘International’ ward with the ‘Russian’ sailor, an Indian or Pakistani sailor and a young Belgian lad who’d fallen off his moped.

Every morning a nun with a splendid moustache would notch up the tension on this halter I had to wear, supposedly to straighten up my collar bone. Whether it did I doubt it but she seemed to enjoy inflicting a bit more discomfort.

Breakfast was a large bowl of milky coffee with bread and jam.

Then the highlight of the day, when we were all washed by a team of delightful Belgian nurses who weren’t dressed as nuns and looked like they’d just stepped out a film.

I could go on with this story for a few more pages but suffice to say the weather transformed to a heatwave, Ron drove me home to England and when I presented myself at the local hospital in Ilford the doctor was bemused to see my Belgian halter which he’d, up ‘til then, only seen in ancient textbooks – calling in nurses and colleagues to view this medical aid from a bygone age.

He replaced it with a figure of eight bandage which resembled those Tour de France heroes of yesteryear who wore spare tubulars wrapped around their shoulders.

In hindsight I might have been better off with my Belgian halter as a couple of weeks later I took a tumble on some gravel and managed to re-open the fracture so had to ride home about fifteen miles one-handed from Ongar to Hainault.

* * *

Part Two: Belgium 1972

The ‘Russian’ in the bed diagonally opposite to me in our hospital ward, was, as Hugh Rainbird suggests, most probably from one of the Baltic States at that time part of the Soviet Union. Ron Pannell quickly dubbed him ‘Ivan.’

Every day Ivan received visitors, presumably from the Soviet Consulate or Trade Delegation, who brought him fresh fruit and red wine, perhaps as an enticement not to jump-ship.

It soon became clear though that he was more interested in getting stuck into the grape juice every afternoon than claiming political asylum.

With the wine bottle empty, Ivan’s attention turned to the rest of his goodies which somehow didn’t hold the same interest and with a shout of ‘hey Eengleesh’ he would hurl apples and oranges in my general direction, some of which I managed to catch.

The other two patients in our room, a Pakistani sailor, who I think, had broken his leg on board ship and a young Belgian lad of about sixteen who’d come to grief on his moped, never seemed directly favoured by Ivan’s largesse but still managed to benefit through his inaccurate throwing, cricket obviously not being on the Soviet school syllabus.

After the fruit distribution Ivan would sink into a gentle doze which meant the Belgian lad and I could concentrate on watching the Tour when the TV transmission started.

On one mountain-top stage finish we watched as King Eddy was just pipped to the line by Cyrille Guimard who managed to inch his wheel past as the Cannibal raised his arm in a premature victory signal.

After the appalling weather, which had been a feature up of our stay in Belgium until then, the skies cleared, the temperature soared and afternoons in the clinic weren’t much fun especially with stitches in the head and the special collar-bone bridle they’d kitted me with but watching the Tour did help to make up for the discomfort.

Conversation in our four-bed room was limited, the Pakistani sailor spoke some English but when the moped lad’s Father came to visit his son I found out that he had been transported to work in Germany during the war and had picked up a good knowledge of the language. So with his forced labour and my O-level German we managed to communicate.

Before this interlude in the Kinik V-D (an unfortunate choice of initials), Ron and I had been sharing a small apartment around the corner from St. David’s Guesthouse.

The rest of the house was split up into small flats and rooms and let out to students who seemed to spend most of their time running up and the stairs in heavy boots. One was christened, again by Ron, ‘Diver Dan.’

The Peugeot team manager at the time (was it Maurice de Muer?) would occasionally send one or two of his squad, whom he thought were in need of a bit of toughening up, to Belgium to stay at Mrs Deene’s and to ride a few kermis races.

One of these was Guy Maignon who had a fine amateur record and although never setting the pro world on fire still had a good six-year career, four with Peugeot and one each with de Gribaldy and Jobo Lejeune with whom he won a stage of the Quatre Jours de Dunkerque.

Mrs Deene sent him round to us on a couple of occasions and we dispensed tea and biscuits while Ron, who spoke good French after time spent as an independent in Normandie, would chat to him while I bumbled out a few ‘plumes de ma tante.’

Another Peugeot visitor was Ferdinand Julien who rode ten years as a pro for a range of French teams with overall placings in the Tour of 42nd, 32nd, 20th, 19th, 21st, 30th, 52nd and 23rd. Formidable.

Neither of our French visitors were too enamoured of the Belgian style of racing with its attendant pushing and shoving to get on a wheel and out of the wind and were, I think, glad to go back to France.

* * *

Postscript

The passing of time plays tricks on our memory, erasing things and adding her own inventions.

It’s a rare person who has total recall even of recent events so a span of forty-eight years is not easily or accurately bridged; if any obvious or glaring mistakes have crept into these Belgian yarns they are the result of time’s tampering.

The main benefit of this tampering is the way unpleasantness fades from the picture.

The endless training rides in the rain along the canal road to Terneuzen, the bone-jarring cobblestones especially in the Waasland, or the concrete slab roads with gaps which could easily swallow a Clement Criterium or an unwary renner, or pedalling as fast as you could on your biggest gear only to see the guy in front’s rear wheel inching away and to know that soon a chorus of ‘Gott Verdomme!’ is going to be shouted at you by whoever has to close the gap, probably accompanied by a tug on your jersey.

These things pass and no longer seem so bad when looking down the wrong end of time’s telescope.

Other memories remain bright; the time we saw a Mercier-clad figure standing forlornly by the roadside, who as we approached we recognized as Barry Hoban. Out training he had punctured, changed his tyre but realised his pump was back home in Ghent.

Or when passing through Drongen where Walter Godefroot called a gruff ‘Hallo!’, or lining up at the start of a race in St. Niklaas with a young Freddy Maertens resplendent in his Belgian National Champion’s jersey, exuding talent and class and obviously destined for great things but still friendly to an Engelsmann.

Or buying horse steak in the Grand Bazaar or to the baker’s where fresh wholemeal bread would be sliced for you and wrapped in tissue paper with an elastic band holding everything together or buying small sacks of coal to combat the early summer cold of 1972.

Ron Pannell, like so many others, is now at the Grote Kermis in the sky but his memory will always remain bright.

* * *

Many thanks to Norman for his reminiscences, they’ve made Our Vik go all dewy eyed…