Having moved from London in 2016 to Casale Volpe, a small, secluded cycling-orientated B&B in Le Marche region of Central Italy, a gloriously hot July day last summer gave VeloVeritas reader Mike Curtis the chance to meet up and ride, relax and chat over lunch with local ex-pro and gregario di lusso Andrea Tonti.

After a 60km ride over the hilly roads that characterise the area, showers and a dip in the salt-water pool, Andrea and Mike got down to delving deeper into the career of this somewhat unsung hero, who during his career provided unwavering service for his leaders at teams such as Cantina Tollo, Acqua & Sapone, Saeco, Lampre and Quick-Step, as well as the Italian National Squad.

By Mike Curtis

Andrea, first, tell us about your time riding in the U23s…

“I spent four years in the U23 category, the 1995 season at the Mengoni-USA team in Le Marche Region where I grew up [the same Fred Mengoni, real estate mogul from Andrea’s home town of Osimo, who emigrated to New York in 1957 and in 1980 founded GS Mengoni in New York with its illustrious alumni such as Steve Bauer, George Hincapie and Mike McCarthy, and also long-time friend and confidant to a certain Greg Lemond].

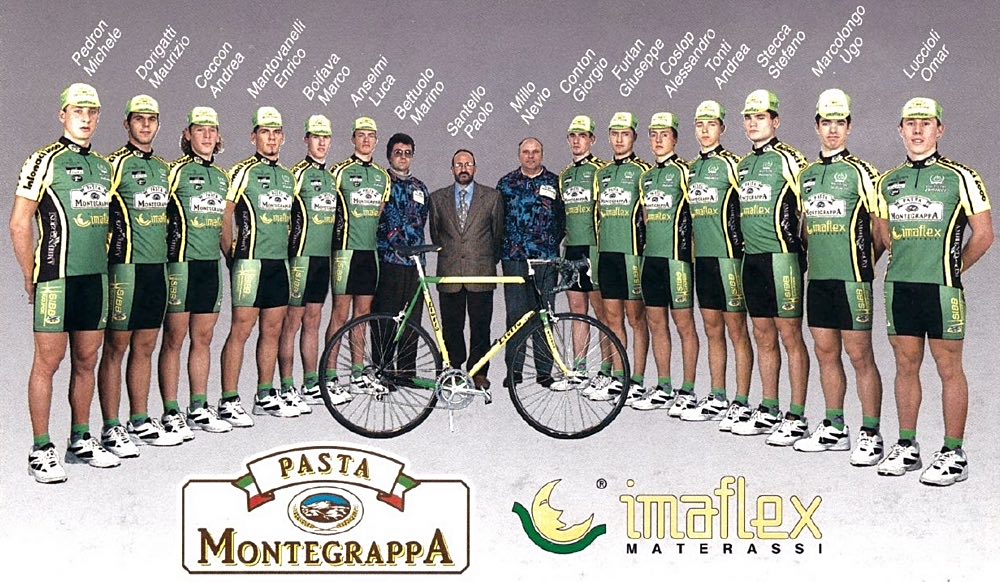

“In 1996 I upped-sticks and left my home region for northern Italy and the cycling hotbed of the Veneto for one season with the Venezia Pasta Montegrappa squad, and it was here where I got my first call-up for the National Team to ride the European Military Championships.

“At 20 I moved and spent two years at Sintofarm-Tolotti in Piacenza in Emilia-Romagna under the guidance of DS Ennio Piscina, in a long-established and very well-disciplined team with some real big-hitters, and it was here that I really learned my trade as a support rider.

“In 1997 I was in the team that helped Oscar Mason win the Baby Giro, even though I was forced to retire following a bad crash on the descent of the Monte Grappa, losing my fourth place on the GC and the lead in the Young Rider’s competition.

“I still had 3 wins for the year, and again represented the Italian National Team at the Open Tour of Okinawa where I placed third overall.

“In 1998, still with Sintofarm-Tolotti, I won five races; Coppa Poggetto at Tabiano Terme, the queen stage of the Giro del Veneto, the hill climb at Como-Brunate, the GP Colli Rovescalesi at Rovescala, and the GP Somma Lombardo, and I got second place overall in the Giro della Toscana and third at the Giro del Veneto.”

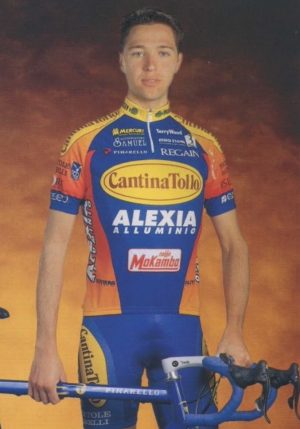

Then at 23 you turned pro, in 1999, with Cantina Tollo. How did you get that ride?

“The team was based in my home region, in Civitanova Marche and it was run by DS Giuseppe Petito with a local youth scout, Franco Gini as part of the management team – he’d noted my ability in the U23s, especially in stage races.

“I stayed there for three years and became a kind of right-hand man for team-mate Danillo Di Luca and for other members of the squad like sprinter Nicola Minali, Dane Bo Hamburger, TT specialist Serghei Honchar, Milan-San Remo winner Gabrielle Colombo and (Amstrong bullying victim) Filippo Simeoni.

“However, despite my domestique role, I still managed a very rewarding 23rd place overall on the GC in the 2000 Giro. It was during this period though that I started having some recurring injury issues that needed time to sort out, and certainly limited how well I was going.”

What was the transition from U23 to pro like for you?

“It was very difficult to be honest, especially the first year; getting used to the increased distances, the higher speeds and bigger gears.

“In the U23s, we’d be riding 5km climbs at 20km/h, spinning smaller gears, but even as a bit of a ‘diesel’ on climbs that suited me before. As a young pro you still tend to lack the required power and resistance of an older experienced climber of, say, 28-32 years old.

“For big stage races with multiple climbs, you really need to be a bit older in my opinion, physically more mature and developed to deal with the higher speeds, repeated longer climbs and push the bigger gears required.

“It’s easier to find a sprinter who’s quick and can win stages at age 22 or 23, rather than a GC contender at that age.”

Danilo Di Luca was your team-mate for six seasons, 1999-2004 – what was he like as a team leader?

“I’ve known Di Luca since I was 10 years old – we’re the same age and competed in all of the same big races together, but were never team-mates before. I was based in Le Marche, he was in neighbouring Abruzzo.

“We’d compete against each other at races like the National Championships or get to ride together for the Italian National Squad.

“Even as a young boy, he was always really strong, same in the U23s and the pros, but even as a 10-year-old in the kids’ races, he was always the one to beat, very quick – he had a real winner’s mentality, as well as the physical qualities to match. A great climber with a real kick, the complete package… if he didn’t drop you on the climbs, he’d beat you in the sprint.

“He was a very good team leader too, always able to motivate his riders; ‘The Killer’ oozed self confidence which in turn translated into a strong belief within the team.

“His declarations of the type “today is a tough stage, and I’m going to win it. Leave me at 3km to go, and I’ll do the rest”, was great for team morale. He’d predict a win in advance, and whilst it didn’t always come off, he’d invariably come close.

“When it really mattered, he certainly had the right mental attributes, a born winner – which he did very often. Not easy to do in competitive sport, when you have to put your money where your mouth is.”

Your first Giro in 2000 was with Cantina Tollo, do you have any specific memories?

“It was my first Giro so it was a big deal for me and very emotional given that Pantani was still riding.

“I was there as a domestique to help Di Luca for the overall. Halfway through he had to pull out due to tendinitis so in the second half I was able to ride my own race and get myself noticed a bit, and I ended up getting 2nd or 3rd in the neo-pro classification, and 23rd on GC, which was a good result not only for me as a young pro and my future, but also for the team. Not bad, given that I’d had to ride for an injured Di Luca and wait for him up to that point, losing lots of time in the process.

“With Di Luca out, the DS in the team meeting gave me carte blanche to ride my own race, go with the breaks and improve my position on GC, to gain some publicity for both me and the team.

“To win a stage though, you’d really have to be in the early break, but there would be the risk that it didn’t come off and you’d lose a heap time on the GC; for the GC you’d need to follow the wheels and focus on that.

“Don’t forget it was also my first time in the Giro – I was unsure of my level, how far I could go, and I didn’t have the experience of racing against other team leaders and battling it out on the final climbs. Also for the team, I was also a bit of an unknown quantity.”

You rode the Vuelta a few times – how did it compare to the Giro?

“Yes, I’ve done the Vuelta five times and the last three (2006-2007-2008) were always used as preparation for the Worlds; five days from the finish you’d pull out, go home and rest in readiness for the Worlds in ten days’ time.

“The Vuelta would finish on the Sunday and you’d meet up with the Italian squad on the Monday, so you’d be mentally fresh too thanks to the break, a chance to spend some time with the family and not be racing or travelling.

“The Vuelta is a lovely race that’s always appealed to the Italians; it’s at the end of season, there’s less pressure, and with late starts around 13:00 – 13:30 (it’s so unlike the Tour or Giro where you’d be up at 6 for a 10 o’clock start) you could get to sleep in a bit, until 10:00, 10:30.

“The stages tended to be shorter than the Tour and Giro too in that era. Even though there would be incredibly tough stages like those to the Angliru and the Lagos de Covadonga, I was never there under pressure as a GC rider like at the Giro.

“Riding the Vuelta for Quick-Step, my role was to help Bettini and Boonen for the stage wins, either accompanying them in breaks or leading out the sprints, and Juan Manuel Garate and Carlos Barredo were there as the protected, home riders for the GC.

“There was always an eye kept on not going too deep before the Worlds, and pulling out early wasn’t an issue, despite the potential tension between the trade team’s DS and the National Squad’s manager – there would be mutual consent, because it would still be an advantage in terms of prestige having two or three riders from your trade team riding well and getting a good result at the World Championships.

“Sure you’d have to follow team orders – they’re paying the bills after all – but you wouldn’t do anything that would compromise your condition, like going on a lone break for 100km when the stage was clearly going to finish in a sprint, say, as opposed to maybe getting in a break with 20 others riders, contributing but not going too deep, and potentially winning the stage.

“You didn’t want to do anything that didn’t really serve a genuinely positive purpose for either the team or your fitness for the upcoming Worlds.”

You were with Saeco and Gilberto Simoni in 2002-2004 – what was he like?

“As a rider, Simoni was clearly a champion – you don’t get to finish on the podium at the Giro seven times, to win it three times, and to win stages at the Giro, Tour and Vuelta without being a great athlete.

“As for his character, sure, he was quite an introverted, reserved and quiet type, but as a team leader at the Giro you knew he’d be able to deliver and the team believed in him, he had the results to back him up.

“In the Giro warm-up stage races he’d always be riding strongly. Let’s say he’d let his legs let the talking, especially in the big stage races where his ability to recover each day was exceptional.

“He wasn’t really made for one-day races like Liege or Lombardy because he wasn’t very quick, but he was very skinny, very light and small and his power-to-weight ratio served him well in the high mountains where the terrain really suited him. In 2003 he won three stages at the Giro as well as the overall.”

The Cunego/Simoni Giro in 2004, tell us about the team tactics and the rivalry.

“Well… we started with Simoni as the designated team leader, with Cunego as a strong support rider having just won the Giro del Trentino in Simoni’s back yard two weeks before, with the team thinking things would go to plan and that Damiano would help Gilberto at the Giro.

“That was the tactic, but the roles ended up being reversed.

“In the early part of the race, Cunego was given his freedom and on the mountain stage to Montevergine he took the initiative, won the stage – he was going really well, super strong – and took the pink jersey from Simoni, who really wasn’t at the same level in 2004 as he was in 2003.

“Once in pink, the team couldn’t really attack Cunego for Simoni’s benefit, they’d only be able to wait for Cunego to blow up – and he didn’t.

“On the 16th stage to Falzes, 217km, where Cunego attacked on the Passo Furcia, Eddy Mazzoleni and I had been in the morning break along with 20 other riders, with the plan that Simoni would come across to join us in the leading group. We saw later on the TV that in fact Simoni had attacked first, but it hadn’t been a strong one, decisive enough to drop his main rivals like Popovych and Honchar.

“Once he was brought back, instead it was Cunego that attacked and got across to us as we waited, and went on to win the stage and took the pink jersey again, this time for good.

“In 2004 Cunego ended up as the UCI number 1, having won around 20 races; in 2003 when Simoni attacked he’d be able to get rid of people and finish alone but in 2004 he just wasn’t as strong and four or five riders would be able to go with him and beat him at the finish. He just no longer had the power to stay away on his own.

“On the other hand, Cunego was going fantastically well; he could drop his rivals and Simoni wouldn’t be able to go after him because of team orders. And don’t forget, it was Simoni, rather than Cunego, that was being heavily marked by the other teams, because everyone thought the younger man was bound to blow up sooner or later.

“All eyes were on Simoni, because even if Cunego were to take a lead of two or three minutes everyone thought that team orders would kick in and Simoni would at some point take the jersey again. Cunego was just so much better that year than Simoni though, on the climbs, in the sprints, against the clock and also the team itself was again very, very strong and experienced that year, nor were there really strong rivals like Contador to deal with.

“Even though Simoni was good enough to finish 3rd overall he just wasn’t at the level of previous years. Unfortunately the tension was really bad between them and it spilled over at the end of stage 18 to Bormio 2000 [where Cunego won another stage, and Simoni called him ‘an ignorant bastard’. ed].”

2006 and a win in the GP Mengoni and 2nd in the Coppa Agostoni. Any ‘what if’s?

“I also won the second stage of the Bicicleta Vasca and got 6th in the GC, and really it was my first year with a bit more freedom.

“September was also the first time I got a call up to the National Team under National Director Ballerini for the Worlds in Salzburg too, albeit as a reserve, where Italy won with Bettini, so it was certainly a good year for my career.

“I’m not sure I changed much as a cyclist but on mental level though 2006 was really significant; I’d had a really bad crash at the same GP Mengoni (one of the two counting races in the Due Giorni Marchigiana) back in 2002 at Castelfidardo where I fractured a vertebra and had to spend 50 days immobile in the hospital at Ancona, so it was a kind of redemption.

“Personally, it was also the year in which my wife gave birth to our son Daniel, so it was pretty good!”

You spent 2007 and 2008 at Quick-Step, how did that team compare to the Italian teams?

“Saeco, for example, was more like a family, where I started to ride in the big races and really got to understand the different roles of team leaders and helpers.

“At Quick-Step things had moved on in cycling… lots of changes. It was a bigger, more international team than I’d been in before, and very professionally organised on every level.

“There was perhaps less direct contact between riders and management, with training and racing schedules now arriving by email.

“It was extremely satisfying to be riding for champions like Boonen and Bettini though, primarily in one-day races rather than Tours. Certainly it was a change in career direction, a choice to return to the role of the gregario.”

What was Tom Boonen like as a team leader?

“Tom is a very open and humble person, but was also very, very strong as a rider.

“Most of all he was incredibly respectful towards his team-mates as a leader, he had a strong tactical nous, and was able to read races very well, without the need for a radio. That always impressed me.”

The QuickStep boss, Patrick Lefevere – tell us about working for him.

“With well over 20 years’ experience in team management, you really couldn’t get much better – he’s effectively the guiding spirit of one of the world’s greatest teams. He has a well-earned reputation for inspiring incredible loyalty from his riders as well as spotting and nurturing new talent.

“He’s dedicated and driven, honest and direct, and he was a great team manager, both of riders but also the financial side behind the scenes.”

The Ballan/Cunego Worlds in 2008 in Varese, Italy must have been special. Was the bonus good? Was Cunego really that upset?

“Well, Bettini had won in both 2006 in Salzburg, and 2007 in Stuttgart, and with the 2008 race being in Italy, we were out-and-out favourites for a third consecutive win, and well prepared both physically and for the inevitable mental pressure.

“But being firm favourites obviously meant the other teams were watching our every move. It was a team with lots of leadership options – Bettini, Rebellin, Ballan – and riding at home meant everyone expected us to win. Lots of pressure, but also a huge desire to do well, riding in front of our home crowd, our own fans, and we really felt the weight of responsibility.

“Ballerini’s tactic was to use our very strong team to make the race hard on a tough Varese circuit and use our advantage to start attacking with 100km to go, then go all out until the finish. It was certainly an extremely emotional win.

“The bonus? The bonus from the Italian Cycling Federation wasn’t better because it was the third win in a row, just the same as previously, but it was still something to be pleased about. The winner also paid out, so Ballan had to put his hand in his pockets for his team-mates, but he’d be getting extra cash from his team in any case, his contract and so on; cycling is a team game with only one winner so sharing the winnings like this with those that helped you do it is simply part of the rules.

“Cunego getting second, yeah, he was initially a bit angry, upset, rather like a striker in front of goal… he wanted to have been the one to put the ball in the net, but fundamentally he was happy because at least a team-mate had won – not only an Italian, but also from the same trade team, Lampre, for the rest of 2008 and also 2009. It’s good exposure for everyone in the team having the World Champion in your ranks.”

What about the Bettini World’s wins in 2006 in Salzburg, Austria (you were a reserve) and 2007 in Stuttgart Germany?

“Yeah, 2006 when Bettini won, I was a reserve, but in 2007 I was in the team that raced, and yes, the expectations and pressure were high for my first time riding for the Squadra Azzura, with a clearly defined role to play in a long, hard race with no place to hide, your contribution vital for the team, and you simply couldn’t afford to have an off-day. It needed a 110% day, 90% just wouldn’t be good enough.

“In 2007 I was also with Bettini at Quick-Step, and in the two to three months in the run-up to the Worlds we rode the same race programme, like the Vuelta, training camps together, were room mates. It created a special rapport between us. We had an excellent party afterwards – we don’t normally drink, but we certainly sank a few glasses together that evening!”

Then a switch to Fuji Servetto in 2009 – was that a good experience?

“I did just one year at Fuji, the 2009 season, but it was a year severely compromised by the operation I had to have on my iliac artery. I’d had trouble all through that winter, didn’t understand what was going on, so got it checked out and was diagnosed with Chevalier Syndrome – a progressive stenosis, or narrowing, of the iliac artery, known as iliac artery endofibrosis. It’s not an unusual issue for cyclists apparently, quite common in fact.

“I was operated on in April in Lyon in France by Doctor Chevalier himself, the very doctor after whom the syndrome is named. Even after the operation, when I started back at the end of August I still had a few muscular issues, and problems with sciatica.

“The next year, 2010, I joined Carmiooro-NGC, a smaller Italian UCI Europe Tour Professional level team (in fact, in 2009 the team was Italian registered, but in 2010 registration was in UK). It was a smaller outfit with less pressure on me and fewer international races, which allowed me to look after myself, have lots of osteopathy, physiotherapy and massage on the leg and recover, and ride a reduced calendar.

“But I still had to have loads of ongoing, daily treatment, because the leg wasn’t getting completely better, back to 100%, and we had the goal of getting to ride the Worlds in Melbourne.”

And in 2010 you did ride Melbourne Worlds (with a Hushovd win), so you were still competitive – why call a halt?

“Yes, I still felt competitive but I was forced to have so much work and therapy on the leg that it was a stressful time.

“Morning was training, every afternoon was driving all over the place to physio appointments for the leg, for my back … it was getting too hard to deal with.

“Every time I went out, the feeling in the leg would be a bit different, okay, but never good and certainly not how I wanted it to be, or like how it was before.

“This effectively signalled the end of my career but I had this last objective of getting a ride for the National Team for the Worlds, and then call it a day… 20 hours a day of training, physio, osteopathy, stretching, yoga, travelling all over Europe searching for a solution. It was getting too much.”

Regrets? / Rimpianti?

“Yeah, the operation certainly shortened my career… without that I still had a few years left for sure.

“But after the operation, I really wasn’t at the level I needed to be. I was maybe 85-90% but in the pro ranks that just isn’t good enough – you need to be at 100%.

“Apart from that, I’ve got no particular regrets, no. I always worked hard so I could ride for successful squads and work for major team captains rather than being in a smaller, inferior team where I’d no doubt have more freedom to win races.

“But this was a personal, professional career choice – like a striker playing for a major team in the Champions League and not always being the goalscorer, rather than being in a second-string team, scoring regularly but never winning anything of note.”

How did you land the role of International Officer for Development Team Nigeria, and the inclusion of the Women’s team at the Giro delle Marche in Rosa?

“I have an Italian friend who has been living in Nigeria for several years, a real cycling fan, and when I stopped competing, he had this idea, this dream, of helping with the development of the cycling scene in the country, but he didn’t know how to go about it, how to start off or what was required.

“So, I said I’d help him out. It was my first visit to Nigeria to see how the existing structure was set up, what I could do, and we started the project together and now he’s the current President of the Nigerian Cycling Federation.

“I go there two or three times a year to organise things and run training camps, group rides, testing and so on.”

You’ve travelled a lot as a pro and now with your own business, Bike Division Tour Operator. Where have you particularly liked, where would you like to visit and why?

“Seriously, Italy really is the best place in the world to live! I really like Spain too, given its culture that’s similar to the Italian one, and then South America; Brazil, Argentina, Mexico …

“One place I haven’t been to yet but it’s definitely on the list is Colombia. I love travelling, it’s a real passion, and I’m lucky enough to have had a job that allows me to do this, and still does thanks to Bike Division.

“I’ve still got the enthusiasm for cycling, and love to get out and encourage people to ride and have fun; it’s a vocation, a bit like being a missionary, spreading the good word, working with kids and helping them out, sharing the enthusiasm for the bike game.

“Without that level of desire and enjoyment, it would just be like any other day job, get up early, work hard, go to bed late… but this is my passion, to ride together with like-minded people, so it’s fantastic.

“I had the idea of starting Bike Division with my wife, and we set it up for exactly this reason, and it just grew and grew, we took people on and it became a proper business with employees, and now it’s well known all over the world.”

Tell us more about Bike Division, what it does and its future projects.

“In the beginning we started by taking Italians riders outside of Italy for cycling holidays, travelling as spectators to races and experiences like Gran Fondo abroad.

“In the last few years we’ve been focussing on bringing foreigners to Italy, creating a network of business partners and experienced ride guides all over the country so our clients can enjoy bike tours that focus on one area, or can choose to travel across several regions.

“The tours are fully customised, personalised, unique to our clients, hooking up with our contacts that have worked in the pro cycling world as riders, team directors, mechanics, masseurs… people with heaps of stories and experiences to share with our clients.

“Our guides are from the locations they operate in so they know the best places to visit, the ‘secret’ routes and the hidden gems off the well-worn commercial tourist trail.

“We strive to show our clients the real Italy, the day-to-day way of life, the local culture, art and architectural history, local food and drink specialities, the whole thing, wrapped up in an enjoyable, challenging cycling experience.”

Interesting fact you’ve mentioned to me on one of our rides: chamois creme – never used!

“It is, isn’t it! Strange, but it’s something I’ve never used, or needed to use – clearly I’m a bit of a tough nut downstairs! I’ve never had any issues in that area to be honest, or any specific problems where I’ve had to use the stuff. All I need is a good-quality pad, and away I go.

“In fact, not many pros use it, to tell you the truth – it’d be the exception rather than the rule.

“Certainly some people might be more sensitive, have more sensitive skin, but pros are used to spending 30-35,000km a year on their bikes, so have bodies that have adapted, evolved to deal with the demands of the sport. We’re used to it, plus the kit at the pro level is really, really good.

“I’d say, at a guess based on experience, that only 20% of the pros use it.”

What was the bike and equipment you had as a pro that you liked the best – our readers like this stuff!

“During my career I’ve used a lot of different bikes, different brands, different models. The bike I used that really worked for me, that had something about it, a feeling, and I’m not totally sure why, was the one I rode for Saeco in 2002, a Cannondale CAAD 4, made-to-measure in aluminium.

“It had loads of innovations for the time, like an integrated Aheadset, an integrated oversized Coda bottom bracket and cranks; especially on the descents it gave a rideability, a level of confidence that I’d never experienced before.

“At the time Saeco had a bunch of riders that were renowned descenders, like Cipollini, Salvodelli and Celestino, and maybe the bikes played a part. They were the bikes I remember as being a bit special, not only great for descending, but also comfortable despite being in aluminium with its reputation for being harsh to ride: we used them for one-day races as well as stages races.

“It was a special bike, to the point that when I rode it, it always had a wow factor. After 16-17 years they don’t make it any more, overtaken by the likes of carbon, titanium, but soon it’ll be ripe for riding in the Eroica!”

And the worst?

“I’m not sure, as an ex-pro, that it would be a good idea to reveal that secret or not!”

With thanks to Mike Curtis for putting this interview with Andrea together.

Check out Mike’s Italian Escape, Casale Volpe: https://casalevolpe.com

https://facebook.com/casalevolpe

https://instagram.com/casalevolpe

+39 0733 661 316 / +39 331 262 0396

Map: https://goo.gl/PYFb4J

And when we can travel again, why not organise

a fantastic bike tour with Andrea and Bike Division.