Billy Bilsland – ‘legend.’ An over-used word but entirely appropriate when speaking of this man; here’s one from our vaults we thought you might like to read:

‘Beelzland! The Engleesh! Where are they?’

Peter Post, Dutch Six Day hardman; Paris-Roubaix winner and manager of the ’70s Raleigh team is enquiring as to the whereabouts of a substantial portion of his team.

It’s the morning of Kuurne-Brussels-Kuurne race, another 200 kilometres the day after the Belgian season opening Het Volk 200 km horror.

The ‘Engleesh’ have in fact bolted back across the Channel after a particularly brutal Gent-Gent (as locals called Het Volk) the previous day.

Billy Bilsland, sole Scotsman on the squad and indeed in the continental peloton, fixes Post with that cheeky Glasgow look.

“Should you no’ know that? You bein’ the manager!”

Post was not a man to be messed with – but neither was Billy Bilsland.

The last 40 years have seen Bilsland lose some hair and gain a few pounds but those square shoulders betray the powerful build that took him through five seasons as a well-respected European professional.

The easy laid-back attitude that helped him shrug off the knocks is still with him.

Talent Plus Smart Training

Cycling was in his genes, born in 1945 to cycling parents, his father being a member of a winning Glasgow Wheelers Scottish 4000 metres Pursuit team in the 30s.

The young Bilsland showed precocious talent, taking the Scottish 25 mile time trial title at the age of 17.

The Scottish titles followed rapidly, the ‘25’ again, 50 mile time trial, three mile grass track, 4km. Pursuit and Road Race.

Bilsland’s coach at the time was Jimmy Dorward, the two were among the first to use a scientific approach to training, embracing interval training before it was in popular use.

Miles had their place but quality came before quantity – albeit the number of repetitions he did would terrify a track man or short distance time triallist.

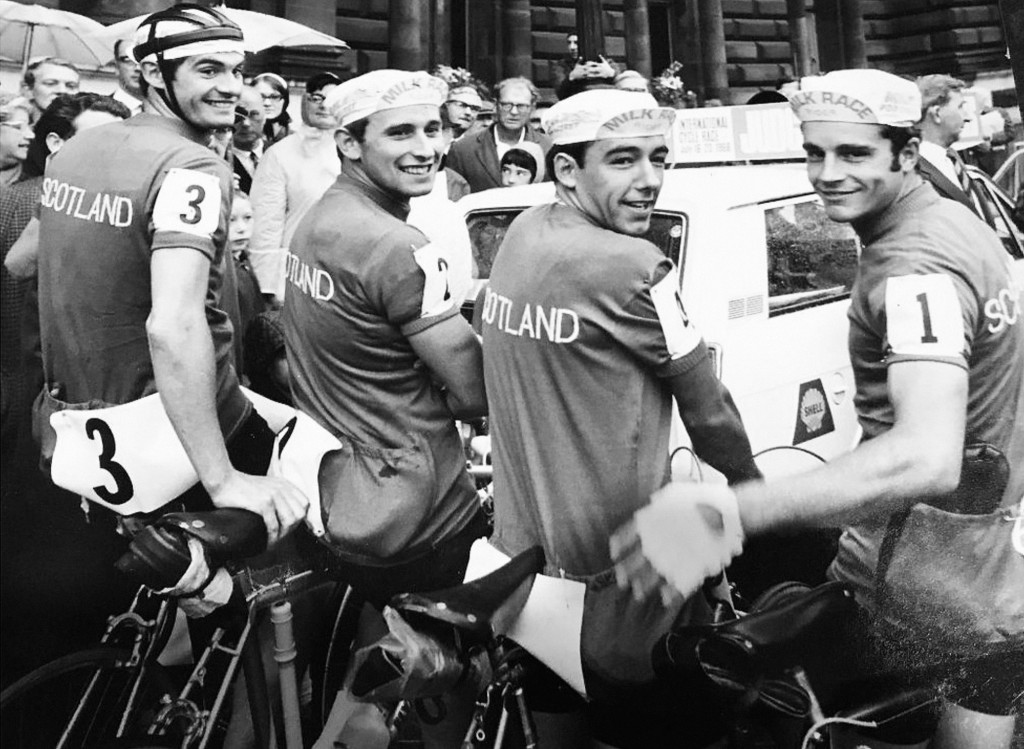

A stellar international amateur career ensued with stage victories in The Tour of Czechoslovakia, Peace Race, Tour de l’Avenir, Scottish Milk Race and Milk Race.

He rode the 1968 Olympics, making it into the winning break until a puncture ended dreams of a medal.

On The Verge Of The Big Time

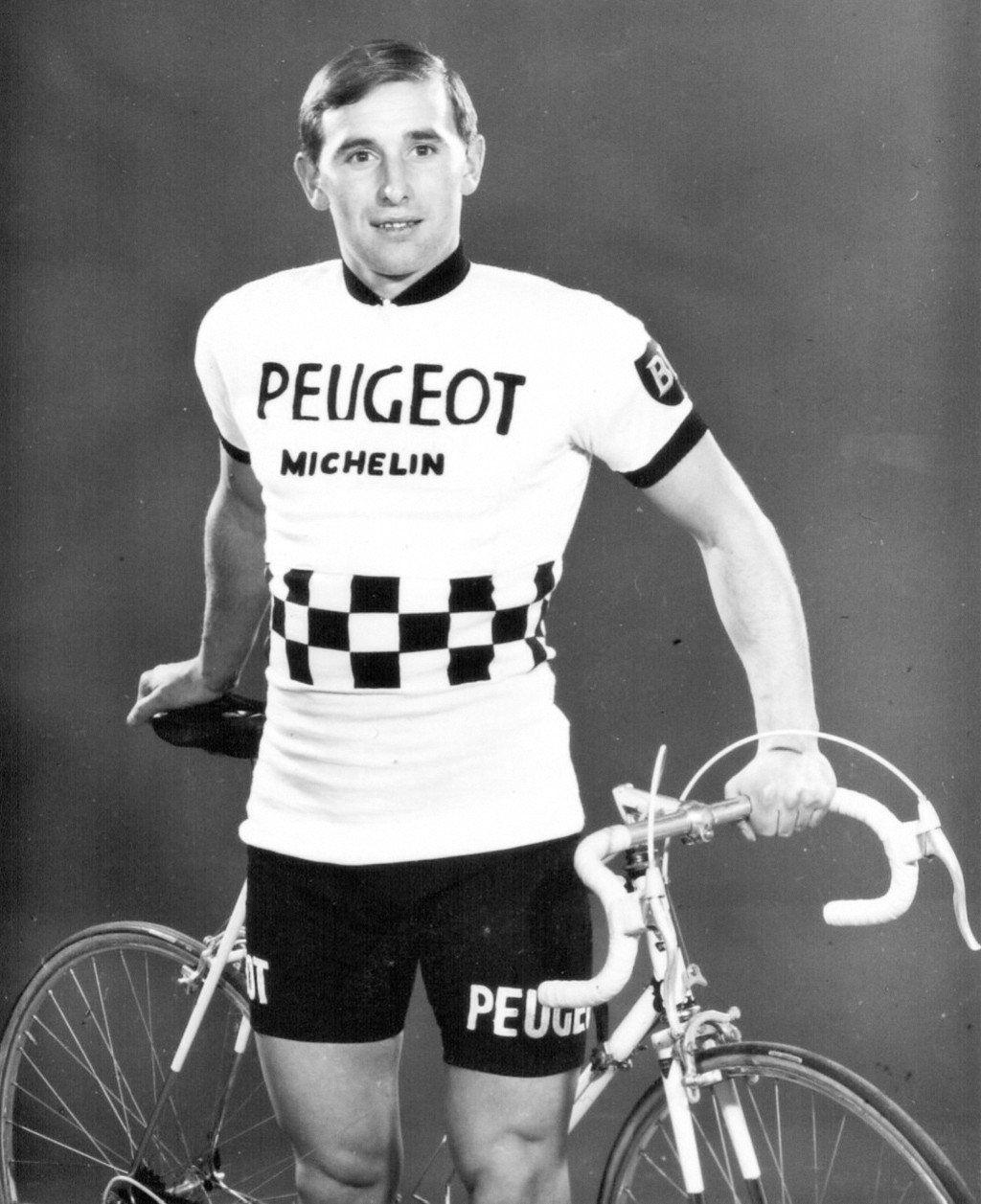

His last year as an amateur 1969, was spent with Peugeot ‘feeder’ team, C.S.M. Puteaux in Paris.

Two amateur classics and 17 other wins meant there was no problem with a contract and 1970 saw Scotland with a pro in the ranks of one of the most glamorous squads – Peugeot.

The early years of his career are well covered in dog eared scrap books kept by his mum; she would catch the bus into Glasgow and buy l’Équipe to clip the articles about his latest successes.

The scrap books become noticeably less comprehensive however after the Rubicon to professional life was crossed.

I ask about this;

“Well, it was my job then.

“I was doing it for the money.”

The squad started the year skiing, however management warned the riders that anyone breaking a leg would have their wages stopped forthwith!

Bilsland rode the inaugural meet at the Grenoble velodrome and landed the biggest prime of the night – 100,000 ‘old’ French Francs.

The Riviera training races were next before heading north to Belgium and the real races.

To The Heartland

As soon as he turned pro the flat in Paris had to be surrendered and Bilsland settled in Ghent, capital of Flanders, cycling heartland.

In one of his first kermis races he followed the traditional protocol of knocking on a door on the circuit and asked the house holder if he could change in his kitchen or garage.

The dour Flandrian beckoned him in and told him he would have some hot water ready for him at the finish.

‘Francais?’ he enquired.

‘Non, Ecossais!’ replied Bilsland.

‘Ahh!’ said the local, his mood lightening as he turned on the electric fire.

At the finish Bilsland was 18th and had won some primes.

“When you say French, I think maybe half distance,.

“When you say Scottish, I think maybe one lap!“

His host told him.

Bilsland spent three years with Peugeot, his team mates included some of the most famous and charismatic stars of the era, Ferdi Bracke, world pursuit champion and hour record holder; Gerben Karstens, Grand Tour stage winner and death defying sprinter; Jurgen Tschan, Paris – Tours winner; ex-T-Mobile supremo Walter Godefroot was also a team mate.

The ‘Bulldog of Flanders’ was as hard as they come and included Paris-Roubaix in his palmarès.

Come Home With Me, Billy

In a Spanish stage race Godefroot discovered that he was the only ‘big’ rider not receiving start money from the organiser. Godefroot told Bilsland that he was going home.

The next stage saw Godefroot slide out of the back of the bunch, pleading illness to manager, Gaston Plaud.

Plaud instructed a miffed Bilsland to go back, look after the Belgian and push him if necessary.

‘Come home with me Billy,’ Godefroot suggested.

Bilsland explained that he was not at the same level in the team and could not just disappear home.

Godefroot abandoned and Bilsland had to launch a long, hard chase to get back to the shelter of the bunch.

As he sat at the rear of the bunch recovering his composure, Plaud appeared in the team car,

“Billy, why are you back here? The racing is at the front!“

It was at these times that Bilsland’s easy manner stood him in good stead, men with a different attitude to life would have been unsettled and de-motivated, Bilsland just laughed.

His first season concluded with excellent rides in Paris – Tours where he was 11th and the Tour of Lombardy where he took 10th place.

There was another highlight that year when boyhood hero, Rik van Looy gave him a hand sling up to close a gap after ‘The Emperor’ had slid off the pace in the string.

Slings featured a lot in Bilsland’s pro career, back then it was standard practice for team leaders to use team mates in this fashion.

Ferdi Bracke’s name cropped up frequently, using Bilsland as a purchase, usually on some brutal cobbled climb.

The Hard Hand Of Peter Post

The Peugeot days lasted three years, at the end of 1972 Bilsland received a better offer than the one on the table from his employer.

Raleigh had decided to expand into Europe using a pro team as the main promotional vehicle.

Bilsland swapped the white with black chequers of Peugeot for the red, yellow and black of Raleigh.

He would stay there for two seasons surviving Post’s cull at the end of the first season.

Much has been said about Post’s dislike of British riders, to Bilsland it was more a dislike of poor results.

At the finish of one race at Menton where the team had not performed to the Dutchman’s satisfaction, the manager, support staff and vehicles were all noticeable by their absence.

Bilsland recalls a 20 mile ride, still in racing kit back to the hotel.

The English riders who were in the team in its early incarnation struggled to find their feet in a strange land with no help given to find accommodation and no allowances made for their low position on the learning curve.

Working Hard For The Money

When it came to distribution of the money after a race Bilsland remembers Post as scrupulously fair.

“After the race he would total up the winnings and then go round the team asking them what split they each thought they deserved.

“He also paid us on the day despite the fact the prize money took weeks to come through from the French Federation.”

Bilsland rode some 100 races per year and always tried to finish.

He took home cash from around 90% of these events.

Even when he was out of luck with placings and primes he could still take money home.

Sitting in a strip in Belgium after a particularly lean race he overheard Bic riders Jean Marie Leblanc (yes, the same one) and Leif Mortensen discussing their travelling expenses. Bilsland ambled over to the organiser and enquired about his own expenses.

The organiser told Bilsland there would be no expenses for him because he lived in Belgium.

Bilsland however, still had his Parisian identification papers, a bad day became a good one in a minute or two of sales pitch.

There were some big pay days too.

When German team mate Jurgen Tschan won Paris-Tours in 1970, Bilsland’s share of the team split was £600, a lot of cash back then.

The last race he rode was the Etoille des Espoirs in 1974.

Life After Bike Racing

A winter selling cars with Arthur Campbell, cycling administrator supreme and Bilsland’s father-in-law opened his eyes to the fact that there were easier ways to make money than chasing breakaways down for Rene Pijnen.

When asked who impressed him most, not surprisingly Merckx but also Belgian world champion Jean Pierre Monsere.

Monsere died tragically whilst wearing the rainbow jersey when a car strayed on to a race circuit.

Regrets?

“None”.

The light race programme that today’s’ riders enjoy?

“Good luck to them.”