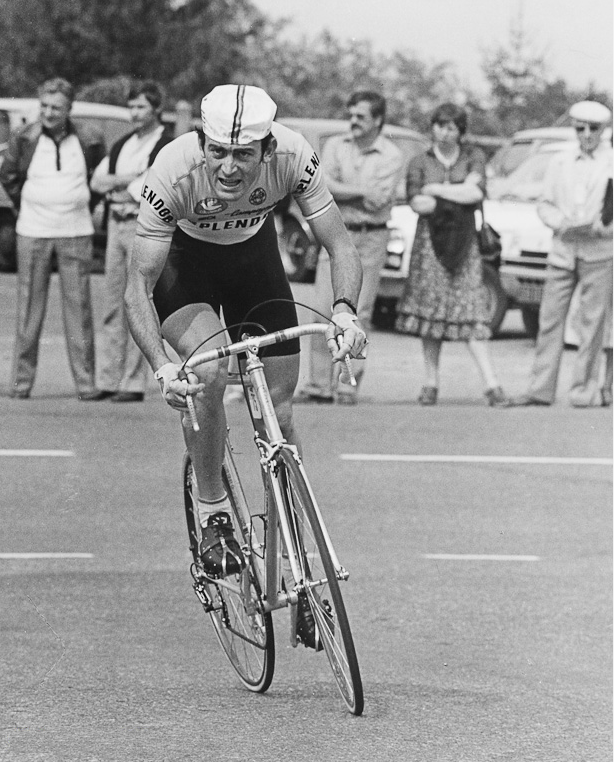

When New Zealander Paul Jesson took the start at the 1979 Tour de France with Michel Pollentier’s Splendor-Eurosoap team he looked to be on the threshold of a good professional career.

After strong amateur results he had been offered a two-year deal with Splendor in the Spring of 1979, and although he was eliminated in that 1979 Tour, his promise was confirmed in the 1980 Vuelta, then held in Spring, when he won the stage to Santander.

During final preparations for the 1980 Tour he crashed into a parked car at the Dauphine Libere, and what ought to have been a routine investigation and then surgery on his injured knee resulted instead in the horror of having his left leg amputated above the knee.

For many it would have been the end, but not for Jesson who fought back to win medals in the world Paralympic road and track championships – and ultimately, a medal in the 2004 Paralympic Games in Athens.

This is his story.

Jesson was 1976 New Zealand cyclist of the year.

That season he won his home races, the Dulux Tour and the Tour of The Southland, which is still a major race in the southern hemisphere season.

Jesson won the Southland twice off four starts and on the other two occasions he was second.

But more significantly that year, the 21 year-old from Christchurch won the five day Etoile Hennuyere in Belgium, the previous year the race was won by Paris-Tours, GP des Nations and Barrachi Trophy winner, Jean Luc Vandenbroucke.

And in 1977 it was Giro delle Regione, Tour de l’Avenir winner and Stephen Roche’s right hand man Eddy Schepers who took the honours.

Hennuyere was a race which the pro team talent scouts paid attention to.

Jesson recalls;

“I was in the New Zealand national squad; we were really just there for training for the Milk Race in Britain.

“We went with no expectations but I ended up winning overall and my team mate Blair Stockwell took the last stage.

“I used to race the New Zealand road season then go to work to get money together so as I could come back to Europe to race in the northern hemisphere summer.

“I’d ride a full programme in Belgium, from stage races down to the kermises.”

Despite Jesson’s major successes in ‘76, he failed to gain selection for his big goal, the 1978 Commonwealth Games in Edmonton, Canada – where the road race was won by Australia’s Phil Anderson.

He explains;

“I had back problems in ’77 and didn’t have the same kind of form as I did during the previous year.

“I was made ‘non travelling reserve’ for the Games but I was going well in Europe.

“I was second in the Tour of Liege and second in the Tour of Wallonia.

“They were both five day stage races with just a few days between them and I was the only Belgian based ride to compete in both of them.”

Jesson’s successes lead him to think of joining the Parisian ACBB club, the traditional ‘feeder’ team for the Peugeot professional squad.

“I used to room with Paul Sherwen and Graham Jones, back then – and Barry Hoban was my mentor.

“Paul wrote me a letter of introduction for the ACBB club in Paris, but Barry said that I would be better to stay in Belgium – there were better prospects of a pro contract for me.

“I was close to Barry; he was always so enthusiastic about the sport.”

And Jesson was soon to join Hoban among the cash men.

“Because of the results I’d been getting I received a few offers from pro teams and in ’79 Splendor contacted me.

“They came to see me and said; ‘we want you to sign a contract with us, we have a tour we want you to ride.’

“I asked how long it was and they replied; ’23 days.’

“I remember saying; ‘Oh, that Tour!’

“So that’s how my first race as a full pro came to be the Tour de France.

“It was jumping in at the deep end but they gave me an 18 month contract which meant that I didn’t have the stress of having to look for a new contract for 1980.”

Starting in the prologue was a totally different experience – and so was the racing.

“There were times when it was very slow, but also times when it was very, very fast.

“I got through the Pyrenees and was strong in the team time trial but whilst I rode well in the Roubaix stage, it took a hell of a lot out of me – more than I realised at the time.”

The Splendor team leader for the ’79 Tour was ex-Flandria star Michel Pollentier, who in 1978 had been ejected from the race for trying to ‘flick’ the doping control by passing ‘clean’ urine – out of a rubber bulb under his armpit and tube – as his own.

It was a crash where Pollentier came down which was to sow the seed of Jesson’s departure from the Tour.

“On the stage from Rochefort to Metz, Pollentier crashed and the whole team had to go back for him.

“I just couldn’t hold the wheels as the team tried to get him back up and I ended up riding three quarters of the stage on my own.

“But my DS kept telling me that things were OK as far as the time cut went – I could have rid1den faster if I had to.

“I used to room with Sean Kelly and that night I got my race clothes ready for the next stage then went down to eat.

“But they told me that I was getting the train home, next morning. I didn’t speak French and was unaware of what was going on – it transpired I’d missed the cut by one minute.”

The 1980 season started well, with a podium place in the tough Nokere Koerse in Belgium – and his next Grand Tour – the 1980 Vuelta – was to provide much better fortune.

“On stage 10 from Burgos to Santander I got in the break. It was a mountain stage with two first category climbs.

“There were about 15 of us away, but on the climbs that shrank to just three, then two – me and the Dutch rider Johan Van Der Meer. [Van Der Meer had already won the highly rated Dwars door Vlaanderen that year.]

“I knew he was a fast finisher and I thought to myself; ‘what would Barry Hoban do?’

“There was a hill coming in to Santander and I could see he was tired so I attacked and he couldn’t stay with me.

“It was downhill to the finish and the crowds were huge – I still get goose bumps when I think about it. I finished 29th overall in that Vuelta and also did a lot of work for Kelly – he won five stages.”

Whilst the stage win didn’t get Jesson a pay rise it did attract interest from ‘super team’ Raleigh.

“They said that they wanted me for 1981 at double what I was earning with Splendor – the contract was to be signed during the Dauphine Libere.”

The prologue for the 1980 Dauphiné Libéré – the traditional 10 day ‘warm up’ race for the Tour de France – was held in Evian les Bains on May 26, over seven kilometres and was won by Raleigh’s Dutch ace Joop Zoetemelk.

That date was to be the low point of Jesson’s life, the English ‘Cycling Weekly’ magazine of the time reported it briefly; ‘Paul Jesson had the misfortune to hit a stationary car in the opening prologue time trial. He cracked his knee and it is feared he may not ride again.’

Jesson remembers little of the day which would change his life forever;

“I was round the circuit three times before the start to familiarise myself with the parcours, but that’s about it.

“I hit a parked car during the race – a Lancia, apparently – with my knee and was unconscious for a couple of weeks after.

“I learned later that I was unlucky with the medical care: I was admitted as the shifts changed and there was no proper control of my circulation. You have to make sure that the blood keeps moving – if there’s no blood circulation for a period of six hours then that’s a real problem.

“I was operated on by a specialist in Belgium who operated on the likes of Michel Pollentier and top moto-cross riders but eventually the leg had to be removed, it was black, dead.”

Stephen Flockhart, a Scottish amateur and fluent Flemish speaker who lived and raced in Belgium at the time recalls a visit to Jesson in the company of New Zealand rider, Maurice Brown.

“We were led into a darkened room, the parlour of the lady of the house reserved for special guests. There was a long dining table set for Sunday dinner, a lot of dark wood furniture, the curtains were drawn.

“It was cool in the room, even though it was – unusually for Belgium – a blazing hot day outside. Maurice and Paul weren’t especially close but they had both ridden the Worlds for New Zealand in Valkenburg in 1979. Maurice naturally wanted to go and see how Paul was – he wanted me to go too, for moral support, I suppose.

“The lady of the house initially wasn’t sure if she wanted to let us see him, but we did meet him. It was very sombre. Maurice asked how he was – what more could he really say?

“And what could Paul say in reply? We were at one end of the dining table, he was at the other, his leg was bandaged and he had crutches. I think we asked him when he was going home, there seemed to be little point in his staying in Belgium, but I don’t remember what Paul said – like I said, a grim day!”

Flockhart was in Belgium during the period of Jesson’s convalescence and remembers that the story was well covered in the newspapers.

‘Splendor made big promises, maybe a job on the team and help with recovery but all this was said in the immediate aftermath, and it seemed it was soon all forgotten. Paul, having had one leg amputated, now found himself unable to pursue the very career he had come to Belgium for.

“There was nothing for him there – to turn up at races as a Splendor mechanic? Watching guys in races he would have been in but for a horrific accident? It would have been difficult for him to stay in Flanders.

“Better to leave, and make a start on a new life, eh? Everything in Flanders would have been screaming at him, reminding him of what he had lost, the “wielersport” is at the heart of life in Flanders, that’s what Paul was there for, but what was the point in his being there now? He was highly regarded by his teammates and there was talk of an annual GP Paul Jesson, but the team really just wanted to put the whole episode behind it.

“In the early 1980s all English-speaking riders were just cannon fodder – the GP Paul Jesson lasted one year, and then was forgotten about.”

But Jesson did not in fact head back to New Zealand;

“I stayed in Belgium with friends until 1984, it was a long rehabilitation and I had to learn to walk again.

“Splendor said they would train me as a mechanic or masseur, but it was too soon for that – they did have a benefit race for me, though. It was a criterium, held on an August evening in 1980 in Dinant, not far from the Splendor factory and where the sponsor lived.

“The race was organised by a Dinant business man Jean-Luc Pecasse and officially called De Eerste Internationale Wielerwedstrijd Emile Wauthy. I think Wauthy was a Walloon politician, an MP – and he was a Burgomaster of Dinant.

“Eddy Merckx was guest of honour – meeting and talking to him was a great experience. And there were representatives of the New Zealand Embassy in Brussels and the New Zealand press there too – I remember they had the New Zealand flag flying.

“Most of the top Belgian pros were there; the Raleigh guys were meant to ride but didn’t show. But one of the riders – Franky De Gendt – and his supporters later organised a benefit football match for me after the season was over. Michel Pollentier won – as you might expect – and there were another four Splendor-Admiral riders in the top ten.

“I also remember being at the Tour of Holland and Sean Kelly giving me his winner’s bouquet – that was very emotional.”

When he did return home, he worked as a frame builder and it was a chance encounter which steered him back into competition.

“I came home, worked as a mechanic for eight years, got married and raised a family – my two boys.

“The late Graham Condon, a famous New Zealand Paralympian used to visit the shop to get the wheels for his wheelchair built. One day he said to me; ‘why don’t you get back into cycling?’

“I said that I didn’t realise I could!

“After that I went on a trip to Europe to see the Tour de France, and the Swart brothers [from the famous New Zealand cycling family – Steve rode the Tour de France for Motorola] arranged for me to do a circuit of the Champs Elysees in the Motorola team car on the last stage.

“That so inspired me that when I got home I bought a new bike and decided that I was going to try to reach the Paralympics.

“It took a lot of work but I won the 1998 Worlds for my class in the pursuit and individual time trial.

“I got to the Olympics in Sydney in 2000 but only finished fourth – which was a disappointment. But I trained hard for Athens 2004 and won bronze in the road competition, which was a combined event, road race and time trial – I was second and sixth respectively and that got me the medal.”

In parallel with his work as a mechanic, Jesson became a fully qualified masseur and has worked on the legs of top NZ cyclists such as three times silver medallist in the Commonwealth Games road race, Brian Fowler and Commonwealth Games road race and Tour of the Southland winner, Graeme Miller.

“I’ve always done massage but I’d like to focus on it more, now. I’ve been with the NZ team at the mountain bike Worlds and been a regular on the Southland Tour.”

Jesson still keeps well abreast of what’s happening on the current New Zealand scene, but feels that PureBlack’s talk of the Tour is premature.

“You require huge sponsorship to realise your Tour ambitions; and people don’t realise the level you have to be at to ride the Tour – some of the best pros we have, guys like Hayden Roulston and Chris Sutton have to work hard just to get selected for a Grand Tour.

“But the improvements in New Zealand cycling over the last few years have been great – having the indoor velodrome has made all the difference.

“The team pursuit boys are now among the best in the world.”

On the subject of regrets, Jesson would rather talk about how the earthquake has affected his beloved Christchurch.

“The whole of the city centre, the old red brick buildings, have all gone and much of the high rise is being demolished – we’ve had 10,000 aftershocks since the main quake.

“There are still parts of the city which are ‘red zones’ guarded by the army and you can’t enter. But there are other parts where you’d never realise there was a problem.”

If the city is anything like it’s Grand Tour stage winning son, it’ll be back.