Before ‘The Plan,’ Britain had a sprinter who looked like he was the real thing.

He had the bulldog build, the aggression and fast twitch muscles; but most importantly – the stopwatch confirmed that he was seriously quick.

It wasn’t until the likes of Craig Maclean and Sir Chris Hoy came along that Paul McHugh’s British 200 metres record was beaten.

He was at the heart of British sprinting for a decade, winning 14 sprint and keirin titles; but never truly realised his potential and was gone from the sport by the time he was 27 years-old.

VeloVeritas thought that his tale would be worth telling…

What are you up to these days, Paul?

“I’m in the computer games business, I’m an animator; I’ve had my own business since 1988.

“We also make TV commercials and do video effects for films.

“We have offices here in Warrington and in London – that’s the centre for most things so I find myself there, more and more.”

Why sprinting?

“I come from the North West – road racing was big there, but there used to be a track at Kirkby and I joined the club.

“I saw the track and thought; “I’d like a go at that!”

“I was about the 13 and got the usual kicking that you do when you first start.

“The best I did as a schoolboy was bronze in the British Schoolboy Sprint Championship.

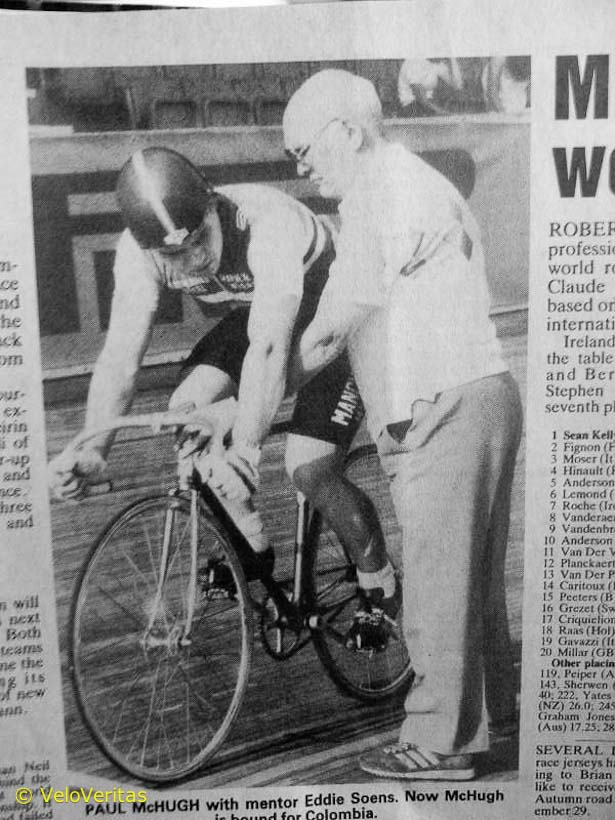

“But when I was 15 I met Eddie Soens; he said he usually didn’t work with anyone as young as me but he made an exception and began to work with me.

“He was a legendary coach and an inspiration, one of my motivations was that I never wanted Eddie to see me throw the towel in; I’d suffer but never ‘call it a day.’”

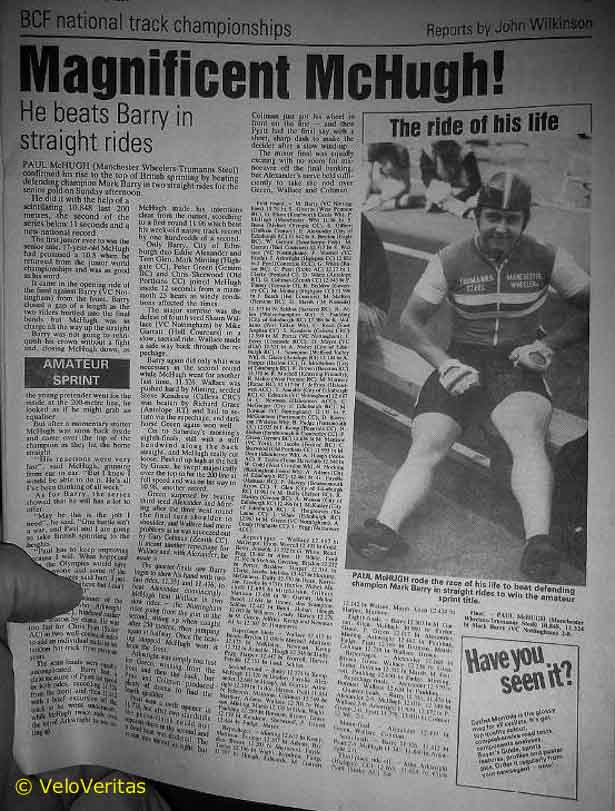

You won the junior and senior sprint titles in 1984.

“I would probably have won the junior title in 1983 but I was larking about with my brother and put my arm through a window.

“The next year I came back with the intention of winning both – I was totally focussed.

“I simply didn’t expect not to win – I had so much confidence.

“Before the finals I couldn’t wait to get on the track, I knew I’d smash him (reigning champion Mark Barry).”

McHugh’s win in the senior championship came during the National Championship week on the Leicester track – but before his win in the junior title; remarkably it was his first national title.

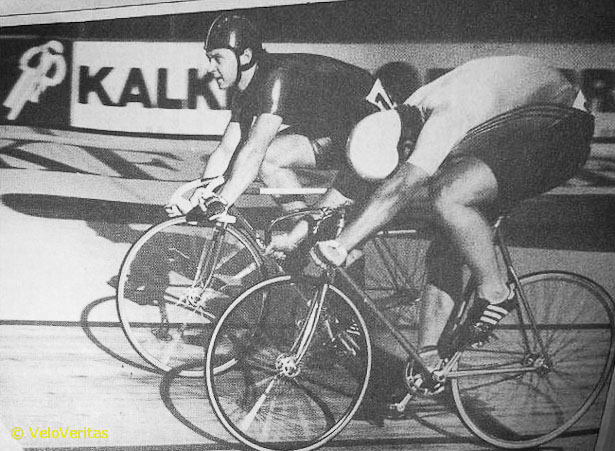

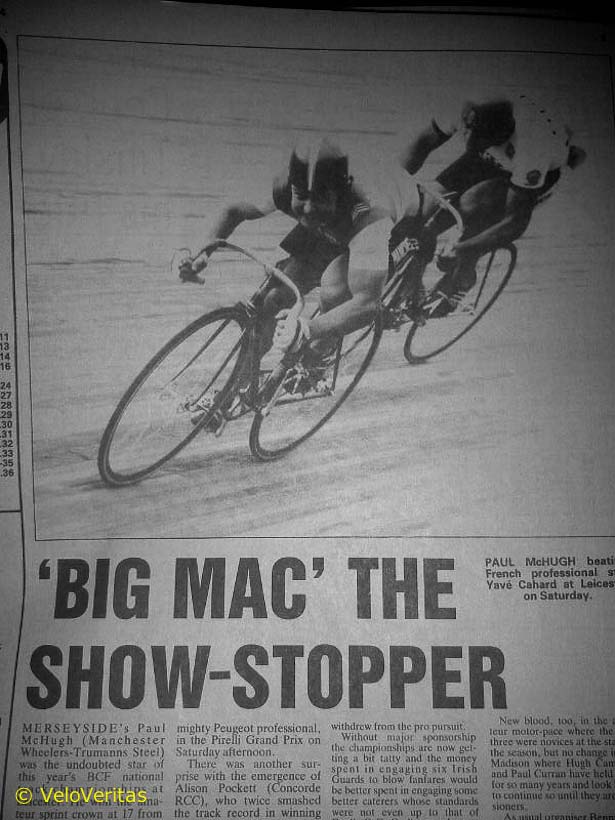

During the course of the week, McHugh also broke the British record with a 10.8 and won the Pirelli Sprint GP – beating highly respected Frenchman, Yave Cahard.

Cahard was nine times a national champion, a former world tandem sprint champion and a silver medallist in the sprint at Worlds and Olympic level.

We put it to McHugh that he had the world at his feet but never seemed to capitalise upon it.

“It’s not a thing I’ve talked about much but I sustained a bad injury during the World Series in Australia.

“I was warming up and I felt something ‘snap’ – it was a big stabilising muscle which runs across your buttock and hip.

“I didn’t realise but I did myself a lot of damage with that one and it held me back a lot.”

How did the BCF (as British Cycling was back then, before they dropped ‘Federation’) react when you won the two sprint titles?

“The BCF didn’t give much of a rat’s ass – at first it was; ‘the kid’s gonna do this and do that’ but it didn’t work out like that.

“Eddie had his admirers but he had his enemies too, he was straight talking but a lot of the people who didn’t like him were fearful of him and as long as he was alive they kept their distance from him – and me.

“But when he died they saw their opportunity to have a go at me – I’m a bit like Eddie was, ‘a spade’s a spade.’

“I had run-ins with authority here and in Australia – and on some of them I didn’t do myself any favours, I can see that, now.”

It must have left a hole in your life when Eddie Soens died?

“Massive – I’d been in Stuttgart with Eddie for the 1985 junior Worlds, before the Nationals.

“In the semis I was one ride up and in the second ride one of my Clement white strips blew out and this massive East German I was riding against rode over me when I was on the deck.

“He pressed my knee so hard against the frame that it bent the tube.

“I had to ride my brother’s bike and it ended up that the German beat me 2-1.”

The ‘massive German’ was Heiko Rosen who went on to win silver. Cycling Weekly of the time said;

‘The deciding ride was a shoulder-to-shoulder confrontation until the final banking. McHugh had the inside, clearly on the sprinter’s line, but the German came over the top to not only shut the door in the Englishman’s face but to slam it violently.‘

The GB team protested, but to no avail – how times change.

“In the ride for the bronze, I couldn’t care – I was there to win and I finished fourth.

“Eddie was with me at the British sprint championship, which I won, beating Eddie Alexander in the final.

“I went home after that but Eddie stayed on at the Nationals for the team pursuit.

“I received a call to tell me that he’d collapsed at the track but was OK. I wanted to go back to Leicester to the Royal Infirmary but was told he was going to be fine.

“But he died on the Sunday evening.

“I was devastated and wish so much that I’d gone back to Leicester to see him. If Eddie hadn’t died I think my career would have been very different.”

What sort of training did Eddie have you doing?

“Basic stuff, I’d be surprised if they do it much differently even now. I’d do a lot of weights in the winter but for sprint training I’d ride the 15 miles to Eddie’s house, then another three miles to this quiet, straight lane where I’d do four sprint efforts and four start efforts.

“Then I’d ride back to Eddie’s, get a massage and ride home.

“There were no secrets, but I trained at the max – the same drills as Eddie had Gordon Singleton doing on the way to winning the world keirin title and silver in the world sprint championship.

“At 12 stone 2 I could squat 500lbs, which meant I had a very good power to weight ratio.”

You held the British 200 metre record for a number of years.

“I think it was until Chris Hoy and Craig McLean came along.

“And my times were outdoors, that 10.84 was from the front on 92” I think.

“I also had various track records around the country – Scunthorpe was one and I had the lap record for Herne Hill, too.

“But I look at the modern equipment and it’s just so much more sophisticated than I rode – I’d love to try it and see what it’s like.”

Who were the riders you admired?

“Koichi Nakano, the Japanese keirin rider who won 10 pro world sprint titles, and the Russian world sprint and kilometre champion, Sergei Kopylov – they were my heroes.

“I raced against Kopylov three weeks after I won the two British titles.

“I got an invite to the ‘Caracol de Pista’ in Columbia, which was a track tournament contested over three rounds in Cali, Pereira and Medelin.

“Kopylov won, Nelson Vails – who won silver in the sprint at the LA Olympics – was second and I was third.

“I was 17 years-old.”

How did you sustain yourself financially?

“I was in the Manchester Wheelers and Jack Fletcher, the guy who sponsored the club (owner of Truman’s Steel) helped with support – the Wheelers were the strongest club in the country back then.

“I turned pro for Pirelli after the Wheelers and I also rode for Paragon-Gazelle who gave me some help.

“And of course, there was mum and dad – there were no grants, back then.”

What do you rate your best ride at international level?

“In Australia they ran what was called the World Series on the track – it was organised by the same guy who was responsible for the Commonwealth bank Classic.

“It was fore-runner of the World Cup, held in five velodromes – Sidney, Launceston, Brisbane and Adelaide.

“I raced it for two years and was only beaten once. The sprint and keirin were ‘round robin’ so you had to race everyone, you couldn’t avoid them due to the draw. I liked the lifestyle out there, the preparation, training with the top guys – it wasn’t like that in the UK, it was hard to get guys to train with.

“I enjoyed racing in Japan, too. It was a bit cold and miserable there but you raced a lot and I always enjoyed racing more than training – I could flick the switch.

“I raced against some good guys there – Ken Carpenter, Federick Magne, Erik Schoefs, Juan Curuchet . . .

“I always finished in the first four – you had to get good results or they demoted you to the lower division. I always found that I adjusted to level of the athletes I was racing against.”

Why quit at just 27?

“After Eddie died it just wasn’t the same – much of my drive came from working to match his expectations.

“I came back from Japan and had become very friendly with Frederic Magne, over there. He tried to get me on board the French sprint training programme, but his Federation wouldn’t have it.

“I was always self motivated but I always felt I was fighting against the powers that be.

“My final season was 1994 – I was fourth in the 1986 Commonwealth Games sprint (losing the third place ride off to Scotland’s Eddie Alexander) and couldn’t ride in 1990 because I was professional but by 1994 the Games were ‘open’ and I could ride.

“I was down to ride the kilometre primarily, but also the sprint. I’d been working with Peter Keen – the man who’s originally behind all of Britain’s current success on the track – and had shown good results in the lab tests and at the Hyeres World Cup four weeks before the Nationals.

“Then I heard that they weren’t sending Dave Le Grys, the sprint coach to the Worlds. You need someone with you at that level that knows the score and can drive the motorbike for you in training.

“Of course, I phoned up the Federation and gave them a piece of my mind, which with the benefit of hindsight wasn’t the best move.

“When the Nationals came along they said that the sprint team hadn’t been selected – but it had, my selection had been confirmed.

Cycling Weekly at the time reported that;

‘The BCF’s Racing Committee added a proviso to McHugh’s nomination that he had to be best-placed English rider at the national championships.’

Adding later in the piece;

‘The men’s sprint was the only discipline carrying the top-English proviso. McHugh had earlier expressed his dissatisfaction at the decision not to send national sprint coach Le Grys to Canada.’

– leaving the reader to make up their own mind if the two events were perhaps linked, in some way.

“I took legal advice but the lawyers told me that I was wasting my time because it was a private body.

“At the nationals I set a new championship record in the qualifying (10.854) but in the semi I was disqualified in my second ride and was out – I was riding against Gary Hibbert who didn’t even lodge a protest against me.

“I didn’t get up for the third placed ride and didn’t ride the kilometre – but I came back for the keirin, I’d got my head together by then – and smashed everyone, I won by lengths.”

Hindsight? Regrets?

“There were people on the Federation who used to say that; ‘sprinters aren’t cyclists’ but when the team sprinters started to be successful they were right in there to bask in the success.

“When I look back, I should have place myself in an environment where I could enjoy training and live a good lifestyle – Shaun Wallace did that when he moved to the United States and it worked very well for him.

“The best form I ever had was when I was training in Australia.

“Now there’s a pipeline if you’re an up and coming rider but back then there was nothing – although I do accept that the BCF wasn’t in financially good shape.

“But the French were, and so were the Aussies.

“I still feel that I was forced into quitting; the Federation were never on my side. But I was only 27 – look at Chris Hoy, he’s 36 – and I still had a lot of racing left in me. But if you take the view that all that counts is right now, then I can’t be unhappy.

“I have good memories; I travelled a lot and saw parts of the world which a non-cyclist would never see.

“The road I took brought me to where I am now, so no regrets.”