As I write this, the World Track Championships in Melbourne are drawing to a close and once again it’s apparent that the face of track racing is changing.

It’s not long since we joked about the sprinters having to race in lanes.

But, as the prophet Job said, later to be paraphrased by Shakespeare; ‘The thing that I greatly feared has come upon me.

Aussie sprint legend Ron Baensch phrased it thus; ‘it’s not sprinting, it’s a time trial with two riders on the track.’

But it’s not the first time that the UCi has stamped its mark upon the Worlds.

Before the International Olympic Committee decided to chop the kilometre, then the pursuit (we’ll leave aside the madison and points) from the programme, another great event was binned, without ceremony: the motor paced.

The ‘big motors’ were first run as an amateur event in 1893 and as a pro event in 1895 – the amateur race succumbed in 1992 and the pros in 1994.

Carsten Podlesch won that 1994 championship – and still claims that he’s world champion, forever.

Some argue that the ‘stayer’ scene was its own worst enemy with Dan Fleeman’s adage that; ‘there’s no problem in professional cycling which cannot be solved by a brown paper envelope stuffed with Euros’ never more appropriate than in this discipline.

Riders would ‘buy off’ other riders’ pacers only to find that another rider had offered the man in the leather suit even more money.

Way back, the pro event was dominated by British riders, with Jimmy Michael winning that inaugural 1895 event.

But in the time I’ve been involved in the sport – since 1970 – there has never been a GB rider on the podium of the motor paced.

Albeit, we had good riders – Norman Hill and Roy Cox both performed with honour on the continental summer and winter tracks.

But the stumbling block came at the Worlds where a rider had to be paced by a driver of his own nationality.

This meant that British riders were at a severe disadvantage against riders from countries like Germany, Holland and Switzerland which had a rich tradition of stayer racing and a ready supply of ‘cuddly’ mature gentlemen, happy to don the leather salopettes and smock uniform.

There was a loophole for ‘minor cycling nations’ which allowed their riders to recruit an experienced professional pacer – and this enabled six day legend Danny Clark to win in ’88 and ’91.

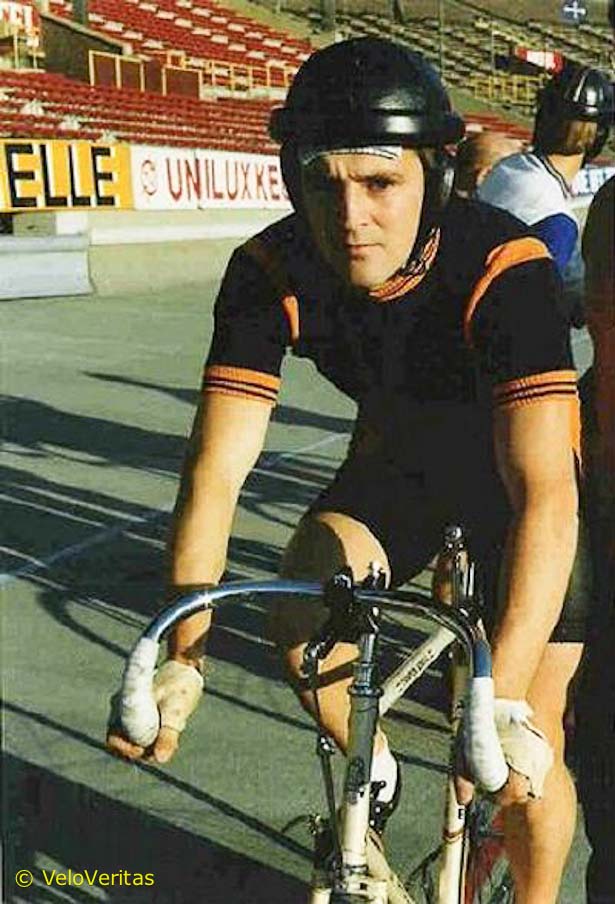

Britain’s last representative in this highly specialised sport – which is still very popular in Germany and Switzerland in particular – was Paul Gerrard.

Gerrard is still active in the sport, chaperoning young GB riders to the Six Days which have junior and U23 competitions.

We caught up with the 58 year-old from Altrincham to talk about the specialised world of the ‘demi-fond.’

British motor paced champion in 1980 and 81 with silver in ’79 and bronze in ’78 I believe, Paul?

“I’ve no idea – I’ve never really been into stuff like that.”

Why ‘stayer’ racing?

“I originally wanted to be a sprinter – I spent six months training with John Nicholson in Denmark – but I’m too small for that discipline.

“There’s a guy called Marvin Smart who paints the advertising on tracks, I was talking to him one day – leaning over the fence as he painted and he suggested that I should try riding motor paced.

I went to live in Holland and approached this house to see if I could rent their summer house. There were trophies on display and it transpired that it was the house of 1951 world professional motor paced champion, Jan Pronk.

“I ended up staying there for six or seven years.”

Tell us about your bike.

“I rode Batavus road bikes but my stayer bike was a Klas Kwantas, a Dutch builder. There was a lot to learn, for example how to bandage on the tyres, so that if you had a puncture they would come off the rim.

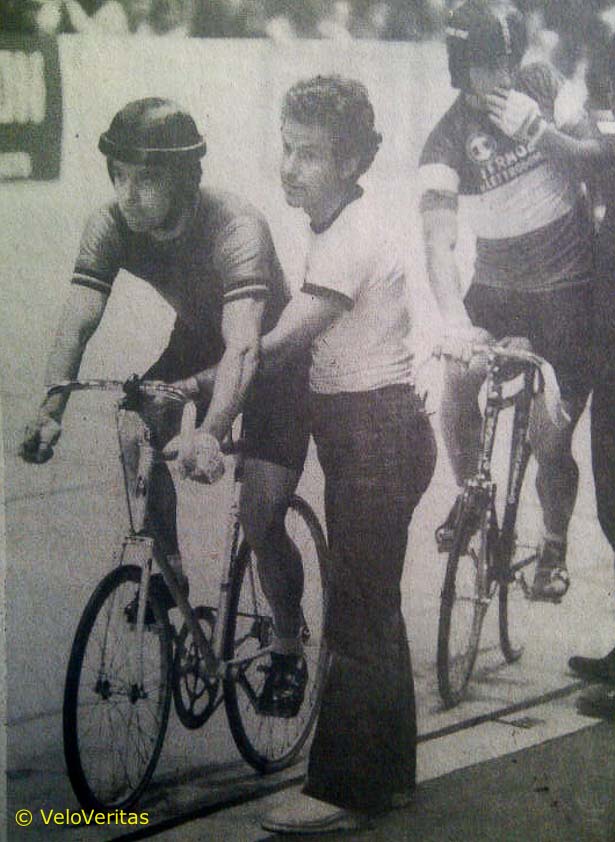

“But my pacer Noel Worby and I sat down with Bruno Walrave (Walrave was the only full time professional pacer in recent years, the others had part time or day jobs to make ends meet, ed.) and we went through all the technical stuff and the rules. I wrote it all down in a notebook, which I still have.

“He explained to us about how to pass, how to stop guys from passing and about position on the bike. Before the current UCi regulations about bike measurements came along there were already strict rules in place for motor pacers about where you could sit in relation to the bottom bracket and such like.

“Most riders tend to sit lower than in a normal track position but you want to sit upright, as close to the back of your pacer as the regs will allow. At the Ahoy in those days I used to ride a 68 x 18 gear but at Amsterdam you’d go as high as 70 x 14. You had to have all the chainrings from 65 to 70 so you could get the right gear for every track.

“The 333 metre concrete track at Bielefeld in Germany was about the fastest. They had big 2.5 litre pace bikes and the roller was set tight in – the closer to the roller, the faster you go.

“But on an outdoor track like that, the wind is a big factor – something you don’t have to worry about on an indoor velodrome.”

Did you have the classic stayers’ silk fronted wool backed jersey?

“I think the British clothing manufactures Gibbsport – who were my sponsors – made me one up.

“The idea was the silk slid through the air but the wool caught the airflow that was coming around your back to help draw you along.”

How do you train for the discipline?

“I rode the Dutch crits which kept me in shape. But to tell the truth, if you have a good pacer then it’s 75% his ability and only 25% yours.

“At the Worlds in Brno in 1981 I was flying in training behind the Dutch pacemaker Joop Zijlaard. The UCi had said that they were thinking of changing the rule which said you had to have a pacer of the same nationality. But the mistake we made was to be seen to be going so well in training – the Japanese were videoing our technique, we were going so well.

(As Gerrard’s British pacer, Noel Worby said at the time; ‘it’s funny, there was no trouble until that training session, but Paul was showing great form and straight afterwards the protest went in.’)

“The difference between Joop in training and Noel in the race was 1.5 seconds per lap. The best pacers even know how to prevent riders from passing them; they twist their body and direct the air flow on to the opposition. If that’s done to you for a couple of laps, you’re finished.”

Did you ride the Euro stayer circuit?

“I rode all over Europe, the different tracks paid different contract fees – your longest race would be one hour.

“Bielefeld was one of the fastest and the Oerlikon track in Zurich was very fast, too.

“The first race I rode at Oerlikon I was paced by the Swiss pacer Rene Aebe and it was just a phenomenal experience.

“Pacers talk about their ‘abri’ (French for ‘shelter’, ed.) the area behind them – his was phenomenal, it was almost easy racing behind him.

“I enjoyed riding all of the tracks – on the indoor tracks there was a compulsory gear that we all had to race on; but some of the riders rode over size rear wheels to give them a little higher gear.”

Aebe apart, who were the other good pacers?

“Noppie Koch, the Dutch guy was cool, an exciting driver, we did a lot of races together.

“Joop Zijlaard was good and Bruno Walrave, of course.”

Did you get much help from the British Cycling Federation?

“Not a lot – they nominated you for the Worlds and that was about it.”

“Don’t you catch a lot of fumes?

“I never got any, behind the bike bikes or the Derny – I loved racing behind the Dernys, too.”

Was it as corrupt as the rumours suggest.

“That was one of the reasons the UCi took it off the programme.

“It never happened to me but that was because I was never in a good position at the Worlds due to the ‘pacer and rider from the same country’ rule.

“It was waived if you were ‘non-European’ though and Danny Clark was able to exploit that.”

And why did you call a halt when you did?

“I was getting too old; I rode crits in the UK at the end of my career but I was going backwards – it just wasn’t the same …”