It was completely surreal. It was the 26th of July last year, and we were in Lourdes, sitting in a neon-lit, scruffy, greasy-spoon café at 1:00 in the morning. Our pizzas were cooking in the oven, but we weren’t really that hungry anymore. We had travelled to the summit and back down again today, both literally and metaphorically; we’d had a wonderful day working on Stage 16 of the Tour de France which took the race to the ski station, 5,600 feet high, at Gourette – Col d’Aubisque in the Pyrenees, and it had been turned completely on its head.

Trying to process the day we had just experienced, and to make sense of it all, we sat at the table outside the café with our drinks – a coke for me and a coffee and a cognac for Ed – and we watched the hordes of teenaged children (on a “religious pilgrimage” to the town with their school no doubt, and having ditched the chaperone) wander loudly up and down the street, eyes wide at the thrill of being out so late and parent-free.

We were equally as dazed. Two hours before, whilst slowly making our way in the darkness back down off the Col d’Aubisque, we’d learned that the Yellow Jersey, the leader of the Tour de France, Michael Rasmussen, had been pulled from the race by his Rabobank team after winning the stage earlier in the day. As everyone knows now, Rasmussen was kicked out of the race by his Dutch team for lying about where he was in June – he had said he was in Mexico when in fact he was in Italy.

The Cofidis team had also been asked to leave the race that night after their rider Cristian Moreni was greeted by the police at the finish line and marched to the back of the squad car, pausing only to put on a long-sleeved warm jacket, prior to being taken to the station in Pau to learn of his positive test result for testosterone a week before. Two days before this, the race organisers had also asked the Astana team to withdraw after Alexandre Vinokourov had tested positive for homologous blood doping. Vinokourov’s Astana team accepted race director Monsieur Prudhomme’s polite invitation to “leave peacefully”. T-Mobile’s Patrik Sinkewitz, then hospitalised after a nasty fall in the Alpes, had also tested positive for testosterone, although the German rider’s test was carried out in June so his team was allowed to remain in the race.

And so we sat in the café in silence, stunned.

We noticed the gloomy-looking group of Dutch folk drinking at a nearby table, their bright orange Rabobank scarves and caps lying discarded on the table, and as we sat there, just two cycle racing fans completely blown away by the day’s events and by the cumulative doping stories in the race, Ed looked sadly at me and said: “D’you just want to go home?”.

A few hours earlier it had all been so different.

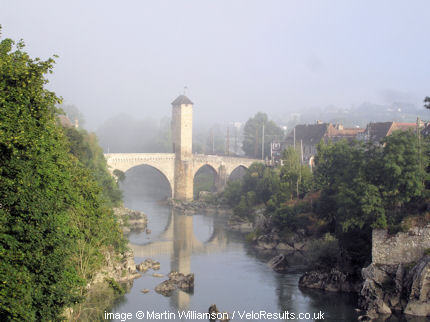

The stage had started at the foot of the Pyrenees, in beautiful Orthez, where Ed and I roamed around the town, looking for interesting things to photograph and riders to speak to. The town’s brass band blasted out the oompah music, and the place was packed with people, but with the Press Passes, or “Creds”, around our necks, we got pretty much anywhere we needed to. Breakfast was coffee, sausages and eggs in the Village Départ, but we noticed that there were more policemen than riders doing the same.

The day was already very warm as we strolled around the team busses and chatted to friendly faces Charlie Wegelius (Liquigas), and Dario Cioni (Predictor Lotto) and Geraint Thomas (Barloworld) both of whom we’d interviewed on the day before (the Rest Day) at their team hotels. The talk today was of course all about Vinokourov, and Ed was working on the piece for Pez which was to include riders’ views on the situation. To a man, they talked about it, but made it clear that they would rather not. These guys might be pro racers, but they love cycling as much as we do. They were simply sick of this situation, sick of the (albeit justifiable) focus on doping, sick of the constant doping-related questions. Charlie gave a heavy sigh and told us: “Guys, I just wanna talk about the bike race”.

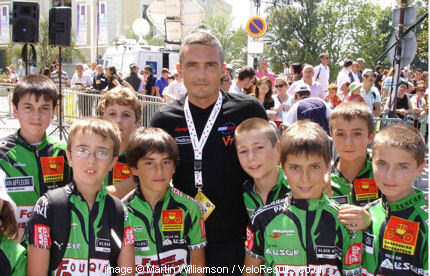

Rather appropriately, we found ourselves next to Richard Virenque, sporting his Eurosport commentator’s shirt and a huge grin. Ed said hello, and asked him a quick question, to which Virenque replied in perfect English and with a wry smile: “Sorry, I don’t speak English”. I asked him for a photo, and he gathered a group of young local cycling fans around him, saying: “Les enfants – ils sont le futur!”.

Our aim that day was to drive the entire stage just in front of the race caravan, and to get a flavour of the stage from the fans perspective at the roadside by interviewing them. We paused at “Kilometre Zero”, the official start, to take stock and savour the moment. Ed said to me: “This is special. Not many people get to do this, and even if they are allowed to, they choose not to”. Here’s why; it was totally exhausting. Most of the thousands of press folk working on the race don’t drive the parcours – they take the motorway or the officially mapped “Off-Race Route” to the finish, and watch the race action in the press room, on the big plasma monitors showing the Eurosport coverage.

In fact, we didn’t see another press car all day (you can tell the type of activity the occupants are involved in by the colour of the stickers on the cars). We’d made it our mission to drive the entire parcours, over the 5 mountain passes which included the Port de Larrau and the Col du Marie Blanque before finishing on the top of the Col d’Aubisque, so we set off 30 minutes in front of the publicity caravan and during the course of the day tried to speak to as many different nationalities of roadside spectators and fans as we could.

It was marvellous. We drove over these famous climbs and talked to lots of fantastic people from all over the world: thousands of youngsters from the Basque Country, each one draped in bright orange hats and T-shirts. There were people from Japan, Scotland, Wales, Norway, America, Sweden… We would stop the car, jump out and chat to them, swap a cap or some other gift and take some photos, before having to charge up the road to make sure we stayed out the way of the first of the caravan vehicles.

We stopped to talk to two Irish couples, who had followed the Tour together every year for the last 8 years. A quick chat about the race, and about Vino’s team (“Team Mafia” we were told they knew it as), before we were offered some wine. “Thanks, but I can’t, I’m driving” I told the friendly woman. “Och, well then, you’ll have some cheese, sure”.

At the bottom of the Col du Marie Blanque we chatted to a large family group from Denmark. Many of them were wearing bright yellow “Le Tour” T-shirts, and the kids had their faces painted with the Danish National flag – they looked great. They were entertaining themselves by drawing giant chalk chickens on the road in honour of their hero, and rehearsing their chants for when the riders came past – only an hour or two to go now guys! They gave us a demonstration: “Rrrrraasssmuuusseeen! Rrrrraasssmuuusseeen!”.

As we drove up the Col du Marie Blanque and the Col d’Aubisque, I was tapping the horn the entire time, letting the crowds know we were there. I was sure I was going to run over someone’s toes, or worse, but just as they would soon do for the riders, the bodies parted in front of us, revealing where the road actually went. Ed and I talked about just how incredibly steep these roads were, and how the car was struggling in first and second gears.

On the Aubisque, we had to leave the car where the Press Centre was located, 6km from the finish line, but the organisers had laid on a shuttle bus service to take anyone from the press wanting to get up to the finish. We decided this would be worth doing, and jumped on the next minibus. For 10 minutes I gazed out the window at the tens of thousands of people at the roadside, eagerness and excitement written on every face, young and old alike. This was what our day had been about, and it was what the Tour should be about too.

After we had looked around the summit for a while, we began to walk back down the mountain, towards the car, planning to watch the action as it passed us.

The last couple of kilometers had barriers in place, and for every three gendarmes who let us walk quickly down the road, keeping out of the way of the passing publicity caravan vehicles of course, there was one who insisted that we get over onto the “crowd side”, and so we had to climb the barriers with plenty of apologetic looks (these guys are as hard as nails, and they carry guns!), and squeeze past the 10-deep crowds. As soon as we were out of his sight we’d climb back over again of course, and flash our Creds to the next policeman. It was very very hot now, and walking downhill for several k’s had made our feet pretty sore.

Before long, we could hear the TV helicopters, and soon we saw them too. Lots of police outriders and official Tour VIP cars sped past, the people all around us were shouting and screaming, and the atmosphere was electric. Then, suddenly, there was the leading duo! “Rasmussen leading Contador!” I shouted to Ed. We grabbed a couple of photos each as they sped past at what looked to me like 20mph, absolutely amazing. I was aware of a few murmurs from some French fans on the other side of the road, but thought nothing more of it.

Rasmussen had just clawed his way up to Alberto Contador after the Spaniard had attacked, and then “The Chicken” immediately piled on the pressure, dropping Evans right in front of our eyes. Leipheimer ground his way up around 10″ behind Evans (later to pass him and latch onto the the leading two), then came Sastre at 50″, Popovych and Soler were at 1’15” and the Valverde group were closing on them at 1’25”. It was amazing watching it all unfold in front of us.

We continued our plod down the hill, watching as riders like Predictor’s Chris Horner rode past us at a speed and demeanour we adjudged more “understandable”, that is, they were crawling up the hill, looked completely out of it, and as we would say in Scotland, “sweating buckets”.

Timing it perfectly, we arrived back at the Plate-Forme du Ley (press car park and centre) and watched on the giant screen along with thousands of others, just as Rasmussen jumped Contador in the last km and sped to a solo win, with Leipheimer taking Contador for second spot.

That was when I knew something wasn’t right – all I could hear around me were boos. I couldn’t believe it: the crowd were actually deriding an apparently fantastic victory by the race leader on the hardest stage of Tour de France, and it just didn’t make sense.

We headed for the “Salle de Presse” (the Press Room, the huge marquee filled with communications technology, wireless broadband, and consisting of various large rooms for photographers and for journalists), and found a spot to sit and work at. While Ed busied himself polishing his words for tomorrow’s article and I edited the photos on the laptop we noticed that a press conference was about to kick off in another section of the marquee.

I left Ed to his work, and wandered through to see who was going to be doing the talking, and found myself near the table where Rasmussen, his team manager Theo de Rooij, and Harro Knijff, the Rabobank team’s lawyer were sitting.

Rasmussen looked uncomfortable, very ill-at-ease.

At first I put this down to him having not 30 minutes ago raced up the mountain at a speed which our little hire car struggled to reach – but I did wonder about those deafening boos.

[vsw id=”hXWveLgocR8″ source=”youtube” width=”615″ height=”450″ autoplay=”no”]

I quickly understood though, as the grilling that Rasmussen got yesterday in his Rest Day press conference at his hotel in Pau continued now. It became the defining moment of the day in my memory, and of course in Rasmussen’s career and one of the most significant in the Tour’s history.

The more questions Rasmussen was asked, the more he stuttered and fidgeted, and the atmosphere in the room reminded me of a pack of wolves circling a wounded animal. Rasmussen seemed to me to be shambolic and unbelievable. I thought he sounded terribly defensive now, and his jumbled answers to the constant “whereabouts” questions from the assembled journalists became increasingly unlikely.

Finally, clearly worried, pale-faced and sweating heavily, he was led away by his management, and I raced through to rejoin Ed, telling him about what I’d just witnessed. Little did we know, that was the last we’d see of Rasmussen on the race that year, perhaps ever.

It took over 4 hours to get off the Col d’Aubisue summit after the race and get to Lourdes, having turned the car around near the top of the mountain after sitting unmoving in the traffic queue for 45 minutes.

We made our way slowly in convoy in the darkness back down mountain the way we’d come. It had been a long day: we were tired, and we just wanted to get back to the hotel, maybe grabbing a bite to eat on the way. Then I got a text message from my girlfriend, watching the news on TV back in Scotland; “Rasmussen OUT the race, suspended by his team for lying to his team“. Ed spent the remainder of the journey texting and calling people to build the picture of what was going on.

Arriving in Lourdes, tired and shell-shocked, we just couldn’t go straight to the hotel and to sleep – so much had happened since the end of the stage. Our day had descended from one of the best days covering a bike race, to one of the wildest, and we felt the need to take a little time to let it all sink in. The tacky, plastic, commercial Lourdes that we were in the middle of suited our mood perfectly: it was depressing. I hope I never feel like that again about a bike race. Ed felt sorry for all those great people we’d met during the day, true fans of the sport: “Those folk deserve better than this“, he said.

This year, here’s hoping for a wonderful celebration of everything that is great about professional cycle sport, and that increasingly rare thing we all want to see: a scandal-free Tour. The Tour organisers are introducing futher measures to try and achieve this, such as fines for the teams and more controls, so all we can do is “keep the faith” and enjoy the racing.