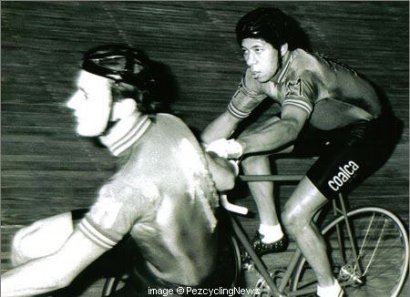

It’s Leicester’s Saffron Lane velodrome, August 1974. The newly crowned British 20 kilometre champion, Maurice Burton waves his bouquet. Sections of the crowd are booing. Is it because the champion rode a tactical race, not killing himself in the winning break, conserving his sprint? Perhaps, but Burton has just made history, he is Britain’s first black senior champion.

Cycling Weekly of the time tells us the championship was a, ‘travesty’ and continues: ‘if Hallam, Moore and Bennett hadn’t run into trouble, Burton would never have been allowed to walk away with it.’

The man that won it was only 18, had made the decisive break and had just beaten the reigning Commonwealth Games 20 kilometre champion, Steve Heffernan and the silver medallist in that event, Murray Hall of Australia into second and third respectively.

It was raining hard in Croydon when we caught up with Burton last year at his bike shop. We don’t normally associate racism and class prejudice with our sport but in Burton’s case they seem hard to avoid. An English mother and Jamaican father gave him his distinctive colour. He grew up in South London and was a product of the Herne Hill cycling school. His club, VC Londres also produced solid track rider and eventual Eurosport commentator, Russell Williams.

Burton’s father forbade him a bike as too dangerous, the strong willed youngster was not to be denied however, cobbled a bike together and told dad it was a friend’s. He found he could win races, he was good at something, a new experience for the quiet working class, black boy. His heroes were Merckx, Sercu and the classy sprint amateur world champion, Frenchman, Daniel Morelon.

Breakthrough

The real breakthrough came in 1973 when Burton won the British Junior Sprint title. Apart from his title win, this was an important year for the developing talent for another reason. He gained selection for the European junior championships (forerunner to the junior Worlds) in Munich. The star of the show was Belgian, Jean Luc Vandenbroucke, (uncle of controversial Frank) who in winning the pursuit, rode through 3 kilometres faster than Knut Knudsen had done in winning the previous year’s Olympic pursuit title.

The young Burton saw the level of support the Belgian had, he was mounted on the back-up bike for Merckx’s hour record with a professional mechanic and soigneur in attendance, all he had to do was ride his bike.

In contrast, Burton’s championship was compromised by mechanical problems and an amateur approach by some of the team officials. The teenager said nothing but decided there and then that Belgium was a place where bike racing was taken seriously, that was where he had to go. In the spring of 1974 his ascendance continued when he won the White Hope Sprint at Herne Hill’s Good Friday meeting.

No GB jersey though

The summer saw that historic 20 kilometre victory, but it has a sequel. That winter at the British Cycling Federation prize presentation in Blackpool, during conversation with officialdom he mentioned he had received an all expenses paid invite to race in the Caribbean over the winter. He was informed that he could not ride in a GB jersey because the invite was personal and not to the federation. Burton told them that his British champion’s jersey would do just fine in that case.

Years later when he was an established rider on the six-day scene, a promoter wanted to run his race with, ‘national’ teams, Burton was partnered with stylish Belgian, Stan Tourne and would be required therefore to ride in a Belgian national jersey. A telephone call was made to the Belgian Federation to seek approval: ‘No problem,’ was the immediate response. ‘I was good enough to wear a Belgian jersey but not a GB one,’ Burton chuckles.

Bike Checks & disqualifications

He does not make a big issue of the prejudice he and his black club mates experienced, but the stories he relates make it clear that it existed. The man who was 4th to Burton in his 1973 junior sprint triumph was another VC Londres black kid, Joe Clovis. Clovis could never figure out why his tyres keep failing the bike tests at his local track when all the other white kids machines passed with no problems. On one occasion he put his wheels in to a white team mate’s machine, the bike passed with no problems. The wheels were re-fitted to Clovis’ bike and his machine tested, result? — failed.

In 1975 the track championships Burton came away with team pursuit gold as part of the Archer RC squad and silver from the madison with Steve Heffernan. But the feeling that he was not a favourite of the establishment was hard to get away from. Defending his 20 kilometre title he crashed within metres of the finish, still recovering from hitting the deck at 35 mph he was told he was disqualified for jersey pulling — the supposed victim of his alleged crime? His Madison partner, Steve Heffernan!

The Learning Curve

That winter Burton crossed the channel and came within an ace of winning the Ghent amateur six, his Dutch partner sold it on the last night to van den Haute and Hoste, (eventual Gent-Wevelgem winner and Tour de France green jersey winner respectively). It was all part of the learning curve.

In 1976 Burton felt he was good enough for a place in the GB team pursuit squad for the Olympics and decided to concentrate on selection. Despite his obvious speed and talent he did not make the squad. His out-spoken, working class team mate Heffernan travelled, but only as reserve, he was another man out of synch with the establishment. In Montreal, Heffernan did not ride, there is a strong argument that if he had, the team pursuiters would have done better than their eventual bronze. Upon his return to the UK, ‘Heff’ dominated the track championships, winning three championships and leaving all those who rode at Montreal in his wake.

A New Beginning

For Burton, it was time to go to Belgium, he would never return to ride another British championship. ‘What was the point?’ he shrugs. He left with :£100 in his pocket, if he won he could stay, if not it was back to England and an electrician’s job in a factory. His aim was to ride the six day races in the winter, first on the amateur circuit, make his name and turn professional.

He also knew that the best preparation for a gruelling winter was a summer on the kermesse circuit in Belgium, racing as often as five times in a week. Plentiful placings and the odd win came and he was able to stay on, pocketing enough cash to support him self. In Belgium there was still racism, but less pronounced – if you could ride a bicycle quickly!

Getting established

The winter of 1976 saw his serious attack on the “Races To Nowhere.” Results came quickly and in November he broke the Ghent track record for 15 kilometres derny paced, averaging 37 mph, among those he beat were Hoste and Belgian Olympic medallist, Michel Vaarten. All told he rode 15 amateur six days.

The 1977 season he again rode Belgian amateur road events, turning professional for the winter season. His pro career would take in 56 six days and eight seasons. World Champion and multiple six winner, Tony Doyle is the only other Briton to have established himself so firmly in this artificially lit and smokey world.

The obvious questions have to be asked.

Which Six is the hardest?

“Berlin, it’s just so fast and the crowd all know the score, it’s real racing, one of my best rides was finishing 5th at three laps there with Roman Hermann.”

Who impressed the most?

“Sercu, he was world sprint champion but could finish the Tour de France in the green jersey, amazing, I can’t think of any athlete in any sport that can compare. I think people forget his dad was a top pro (Albert, won Het Volk in 1947) and he was being groomed to be a star from his early teens.”

Who was the hardest man on the circuit?

“Danny Clark, without a doubt, he never raced as an amateur, he was racing as a pro in Tasmanian carnivals since he was a kid. Only reason he’s still not racing is that the organisers don’t want a guy in his 50s dishing it out!”

Who was the best guy you rode with?

“Roman, he was a good rider and a good guy.”

Do you keep in touch with the guys from those days?

“No, you have no friends on the sixes, especially if you are a new face, you are taking someone’s place. I used to have a beer with Gary Wiggins (Brad’s father) when we raced in Belgium and I still see Roman, we both have holiday homes in Lanzarote and we see each other down there from time to time but that’s about it. After sixes we would all go our separate ways”.

Burton’s worth on the circuit can be judged by the fact that legendary roadman-sprinter Rik van Linden would telephone to ask if he would partner him in forth coming events. The van Linden connection leads Burton into a very specific career high-light. In one edition of the Antwerp six he started with Swiss rider, Rene Savary, van Linden had started the same event with Don Allan. The saddlesores which were to plague Allan’s career flared up and he was forced to retire.

This left van Linden without a partner, he promptly bought Savary out of the race so he could team up with Burton. Faced with a big deficit Burton decide to try and claw back laps in the derny races, which counted towards the overall race lap standings, not just the points scores. Having good legs, Burton geared up to 55×14 and went for it, by the end of the event vital laps had been reclaimed and Burton had crossed the line in first place. The race was, ‘for real’ unlike most derny races and in Burton’s wake were men like road super-star Alfons de Wolf and world motor paced champion Wifred Peffgen, he smiles when remembering that one.

His last six was Buenos Aires in 1984, a serious crash put him in hospital for six weeks and left him with an 8” still pin holding his leg together. Faced with a year of convalescence and then a fight to get back on the Blue Train, as the group of riders at the heart of six day racing is called, Burton decided to call a halt. He was only 28, a further 10 years on the circuit would have been perfectly feasible. Burton doesn’t say it but maybe there had been too many struggles; with the predominantly white middle class cycling establishment; to gain acceptance on the six circuit and to hold his place in that cut-throat world.

On his return to Britain and once his leg allowed, he stuck with what he knew and became a cycle courier. Apart from the devastating Buenos Aires crash one of his lowest points came during his time as a messenger.

“I nearly rode into this guy getting out of a cab, it was Gerrie Knetemann! I knew him and all the Raleigh guys from riding the kermesses. He thought I was just out on my bike, I didn’t make him any the wiser!”

He delivered packages for 18 months. A friend of his, an Australian called Peter Versleydonck was trying to sell his shop, de Ver cycles in Croydon so he could return to the Antipodes. In 1987, Burton finally succumbed to the Australian’s sales pitch and he became a bike shop owner. It was hard going at first, often he would go home in the early hours, having been doing repairs all night. He is still expanding the shop and the builders were in drinking tea and eating biscuits when we met their client.

Burton has worked hard at the shop over the years and is now a Colnago main dealer. A photo of Burton with Ernesto graces the shop window next to a 50th anniversary Colnago. His marketing is aimed firmly at tri-athletes and affluent City fitness types.

Does he still ride the bike?

“Yeah. I did 96 miles yesterday and I’m riding the étape.”

A comeback?

“Me and Heff talk about it, coming back and winning the madison but I’d get too serious and start being unbearable to live with, the wife and kids wouldn’t put up with me! When I do things it’s never half measures.”

Before we leave he shows us his car, a beautiful Rolls Royce, I can’t help but wonder if anyone else who pedalled round those Ghent boards with him back in the 70s has one of these in the garage. A good business, good health, a wife and family, a Roller, and all those memories… surely the struggles have eventually been worth it for Maurice Burton.