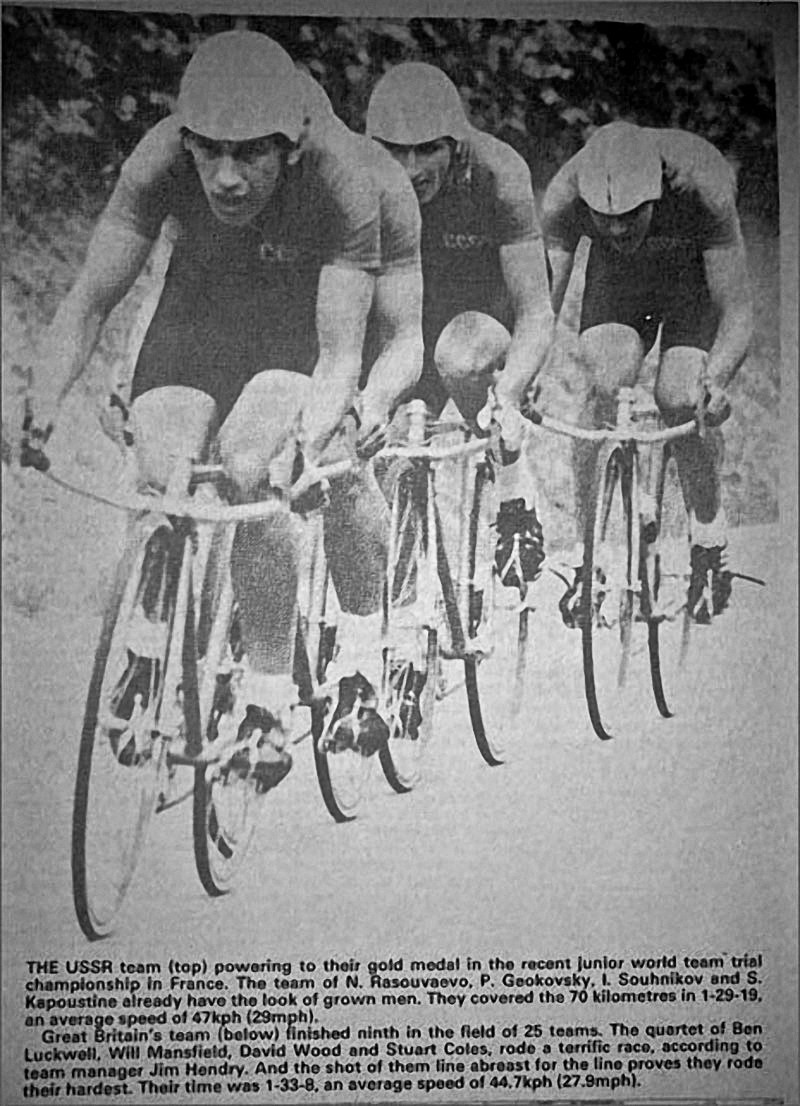

How many juniors do you remember who trained three times every day, clocking up 1,000 kilometres each week? That’s what it took to make Nikolai Razouvaev World Junior Team Time Trial Champion in 1984, but that was a much better option than taking on the Mujahideen in Afghanistan.

If you were a cycling fan back in the 70’s and 80’s things were different – there were amateurs and professionals; the sport wasn’t divided U23/Elite as it is now.

But there was another division within the amateur ranks; there were the East Europeans – and there was everyone else.

The Peace Race, l’Avenir, Worlds and Olympics all bore the big bold stamp of Soviet Bloc nations.

How were they so good?

You can nod knowingly and say well; ‘it was what they were taking.’

Here’s Nikolai Razouvaev’s tale:

Is it true that selection for sports was made according to physical characteristics, when you were at school?

“Yes, the coaches were selecting their recruits based on physical characteristics suitable for the sport they worked in.

“For example, an overweight guy would never be selected for a road cycling school, but he could have better luck going to a wrestling or weight lifting school.”

What were your dreams as a young Russian cyclist?

“Once I realized I was in it for a long term, my number one goal was to avoid serving two compulsory years of service in the Soviet Army.

“We had a system in place which made it possible to be officially in the Army and race at the same time without even touching the military uniform.

“This opportunity was only open to elite racers.

“In cycling, if you didn’t reach elite level by 17 years-of-age, you’d be in the Army by 18 years-of-age.

“At the time, USSR was at war with Afghanistan, we were losing thousands of soldiers every year in that war.

“Afghanistan didn’t appeal to me as a place to die in at the age of 18 years.

“I did everything I could to reach the elite level, including giving up on school, before I turned 17 years-of-age.

“Once I was recruited by Titan, a Soviet version of a pro team, I was given specific goals I was hired for.

“For example, I was told at the end of 1983 season, three months after I was hired, that I was expected to win gold at the 1984 Junior World Championships.

“It wasn’t a dream or something to aim for – they just tell you what results they want from you and you go and do it.

“My next stop was 1988 Olympic Games.

“I delivered the first result but failed with the second. To answer your question – I didn’t have any dreams about what I would like to win.

“I moved from one target, given to me by someone else, to another.

“I got some of them but missed others.”

Who were your idols and why?

“At first, it was Aavo Pikkuus; TTT Olympic and World champion – also Peace Race winner.

“The legend was he could do everything – climb, sprint and time trial.

“As a kid, I was told many times by my first coach: “You want to be like Aavo Pikkuus?

“Train hard, never give up and fight like a dog.”

“Sometimes, I took his advice too literally, especially the last part.

“Then came Sergey Sukhorouchenkov in 1979 and smashed everyone at the Peace Race.

“And then he did that incredible solo attack at the Moscow Olympic road race.

“Watching him win that race changed my perception of what road cycling was about.”

You were World Junior TTT champion in 1984 – what are your other palmarès?

“As a TTT specialist, we were told to keep our heads low in road races or help others when required so we didn’t chase road results as non-TTT riders did.

“Some results stood out though.

“In 1985 we were invited to GDR to race their national championship and we won the team time trial beating all those famous East Germans in their own country.

“In 1989, after I realized I’m wasting my time chasing TTT results,

“I won the Ukrainian road championship beating stars like Oleg Chuzhda, Sergey Gavrilko and Sergey Zmievskoy from a four man break.

“That was by far, my favourite road race win.

“In 1993, I won a pro-am race in Lac-Megantic (Canada), probably the only race that gave me some UCI points.”

Is it true the team had a two year build up for those Worlds?

“Yes and no.

“TTT training was part of my routine since 1983 so by August 1984 I had thousands of kilometres in me of pure TTT training.

“We started targeting the World’s from May 1984 after I made the National Team selection in April.

“By targeting I mean they had to select four guys out of about 10-12 initial candidates first.

“Once you’re down to six, they start to mix things up, trying to figure out what combination works best; who the most reliable riders are and so on.

“Once the final selection is made, you’re only weeks away from the race.

“This is when you start putting everything together, every little detail, polishing it up.

“Without TTT background, you wouldn’t get selected but the actual, targeted preparation was only 2-3 months long.”

Were you a ‘full time’ cyclist?

“Yes, I was paid a large salary by the government and made a lot more than that from being allowed to travel abroad.”

Tell us about your training – did you really train three times each day?

“Yes.

“When I moved to Kiev to race for Titan, I thought they were joking when I was told I would be training three times a day – 40 km first thing in the morning before breakfast, then 4-6 hours main ride from 10 o’clock and another 40 km before supper.

“We were clocking 4-4,500 km per month and I didn’t even turn 18 yet.

“The main rides were not your typical two abreast, long and steady rides; they were filled with 10-25 km intervals repeated over and over again in TTT formations.

“Intensities varied depending on where we were in our training cycle.

“Closer to a 100 km TTT, the intervals’ intensities would reach their peak and we would start hitting our gold standard – full gas 4 x 25 km.

“This is where the coaches were observing and timing everything – how long you pull at each turn, how you pull (are you slowing down the team or raising the pace too much), how long it takes you to get back on the wheel, your body language and so on.

“The 4 x 25 days were the days where the boys were literally separated from the men – guys were cracking on the fourth interval like you wouldn’t believe.

“This is when you would either make or break the team – with only four spots available, the survival game was on, you had to earn your spot which often meant to outplay a close friend.”

You had to ride 50 K home after a TTT as ‘punishment’ for not going well – was that type of thing common place?

“Yes.

“Normally, you would ride home from a race anyway; anything up to 50-60 km was considered a recovery ride and they believed recovery rides were necessary, which is why we rode those 40 km before supper almost every day.

“On that particular occasion you’re referring to, we were supposed to be taken home by our team bus.

“It was very hot and because I sucked the entire race (it was a 100 km TTT), three other guys were smashed too much.

“They told me I needed to harden the hell up and sent me back to the hotel on my bike.”

What about diet?

“Diet, in a Western sense of the word, was never on our mind.

“You have to realize where we lived – a country run by authoritarian government with no free market and no private property.

“The grocery stores were empty.

“You could buy bread, milk, sugar, flour, conserves, candy, fruits and veggies in season, stuff like that, but that’s about it.

“When away from home at races or training camps, which meant more than 340 days a year for me, we were fed in restaurants attached to hotels we were staying in.

“The type and quality of food depended on how good or bad the place we stayed at was or where we were geographically.

“Food was excellent in Baltic States or Western Ukraine and horrible in Tajikistan.

“The question on our minds was about what not to eat rather than what to eat.

“Because food wasn’t always good enough, Titan’s management found a way to compensate that – we were supplied with large quantities of space food, the stuff cosmonauts took with them to space stations.

“This food was neatly packaged and was very high quality.”

What happened to your career after those Worlds?

“It stalled because I made a major mistake – I bet my entire career on a team time trial.

“It seemed like the safest thing to do.

“I reasoned that if I could qualify for the World’s or Olympic Games, there was a good chance of another gold medal, this time in senior ranks.

“This would have set me up for life, especially the Olympic Games, and I could either retire or switch my focus on what I enjoyed racing the most – road races.

“The program I was on was so TTT focused that everything else was set aside.

“I was often told to save my legs during road races, especially the hilly ones.

“The idea behind it was that you could fire on all cylinders only a few times a year and therefore you couldn’t afford to waste your bullets when you didn’t have to.

“This approach didn’t work very well with Viktor Kapitonov, the National Team’s Czar.

“He knew something was on but I received my orders from Titan, not him.

“I trusted Titan too much.

“After all, they turned me from a nobody to a World champion in a year; I had no reason to doubt them.

“They told me I can be an Olympic champion and I believed them.

“The wake up call came after 1988 Olympics when the cycling’s own “iron wall” fell and we were allowed to race for Western teams.

“At the end of that year, the Alfa Lum project, made up entirely of Soviet riders, went ahead but I wasn’t offered a place – I had no results of any interest to a team like Alfa Lum.

“There were a couple of Russian based pro teams brewing in the country, one of them headed by Kapitonov himself who was pushed aside from his National Head Coach position.

“I was on it but I didn’t want to wait for them to organize their game – I packed up one day and went to Europe, hoping to find a contract on my own.

“This was another mistake – I had no idea what a Western society was like.

“Before, I only saw it from the saddle of my bike but didn’t know how it functioned.

“For example, I was shocked to find out a breakfast in Paris will cost you $40 and a night at a hotel $300.

“With my Soviet passport, I couldn’t move easily from country to country either.

“I settled in Denmark, raced there for a while but wasn’t getting anywhere with finding a contract.

“Then I moved to Montreal, raced there for two seasons, won a lot of races and retired in 1996 at the age of 30.”

Did your becoming World Junior TTT Champion gain you much respect/recognition in the USSR?

“Respect, yes, but recognition was limited to cycling circles only.

“No one cares about cycling in Russia.

“I received a year’s worth of salary as a bonus though, which I didn’t know what to do with.”

You rode the Russian Takhion bikes – the position looks severe, with a wider arm position than you would have now...

“Yes, the Junior National Team received the first eight TT production bikes.

“Aerodynamically, I’m not sure how much advantage over a road bike they had.

“The Takhions allowed us to sit lower and closer to each other in a team time trial.

“This latter point is important – the closer you sit, the more drafting you get from the guy in front of you.

“The upper body was a bit more relaxed too.

“In a flat out race, like 75 or 100 km TTT, every little detail counts.”

Was that race on restricted gears – what ratios did you ride?

“Yes, we were restricted to 50 x 14.

“We clocked 1:28 I think in a 75 km TTT which is like 51 km/h average so you can imagine our cadence was a bit high.”

We were always led to believe that it was hard to get equipment in the USSR – is that true, what equipment was on the TTT bikes – what about tyres?

“Yes, equipment was hard to get.

“It’s only when you reach the National team or one of the top tier teams you get a Campagnolo-equipped Colnago.

“For important events, like Peace Race, the World’s or Olympics, they would give you a new bike.

“The stars would get a new bike every spring.

“We were well supplied with cycling kits though.

“But again, only at the top level.

“We raced most domestic events on Soviet made tubulars.

“For international races, if they were important, we were supplied with high end Vittoria or Clement tubulars.”

Eki (Katusha General Manager Viatcheslav Ekimov) rode those Worlds, he won the points and was second to Woods in the pursuit – tell us about him.

“I never got to know him that well – he raced track, although his team would often show up at the road “spring classics” and other races.

“At the ‘84 World’s, the track and road teams lived in different hotels – them near the track and we closer to open roads.

“We went to cheer Ekimov’s team up one day after we won our race.

“We had a brief chat and then I would see him from time to time on the road, say a quick hello and that would be it.

“He had a reputation of a “never die” animal though and everyone believed he could win any road race if he wanted to.”

Do you keep in touch with your old team mates?

“I do now.

“I got in touch with Abdujaporov, Poulnikov, Uslamin, Soumnikov, a few others as well.

“I regularly saw Kashirin in Canada while he worked as their National Head Coach and then he stayed at our place in Sydney during the Olympics.

“Not seeing these guys for years now makes it a bit hard to keep the relationships going.

“I know those who settled in Italy after their careers are still close.

“I guess what was planted back in Soviet Union has some deep roots.”

Please explain how Gavrilko ‘gifted’ the Baby Giro to Ugrumov.

“After Gavrilko finished second to Ugrumov at the amateur Giro, a rumour was going around that he was ordered to wait for Ugrumov after he attacked in the mountains and became a virtual leader while Ugrumov had the leader’s jersey.

“Years later we shared a room at a training camp.

“Gavrilko’s career was going downhill and I asked him if ever regretted following team orders that day; we all knew he could have won that race if he wanted to.

“To my surprise, he told me there were no orders to wait for Ugrumov.

“He said he felt it was wrong to win a race like that.

“You might think he was honoring “the code” but I knew him well enough to know he didn’t give a damn about any codes except what he thought was right or wrong.

“Which is why Kapitonov didn’t want him in a Peace Race – he was his own man and unpredictable on the road.

“He also was a kind of a guy who would buy a dozen saddles in Italy and give them away to his teammates because their saddles were crap.”

Why did you go to Australia to live – and what do you do, now?

“I liked the idea of an English speaking country with never ending summer.

“Australia fitted the bill.

“I have worked in web design industry for several years and this year I enrolled into a law school.

“You’ll probably see me in court soon.”

Do you still cycle?

“I haven’t touched a bike for 12 years after I quit racing but a few years ago I got back into it to lose weight.

“Then I started racing again, both Elite and Masters categories and I still do.

“I love riding.

“At my age, it’s stupid not to ride.”

Has the world ever seen tougher sportsmen than those Soviet riders of your era?

“I think each era has its own tough riders, it’s just we don’t see them as clearly as we used to in the past because road racing has changed.

“Races are much more controlled now with each rider on the team having a particular job to do.

“Once their job’s done, the guys vanish from the race leaving the big boys to sort it out among themselves.

“In the past, races were more open, exposing a lot of riders to unexpected circumstances, forcing them to dig deep to turn things around if they had to.

“It’s not happening that often today I’m afraid but it doesn’t mean there are no tough riders out there in the peloton either.”

Read Nikolai’s story in his own words, in his online book “The Renegade: A Memoir of a Soviet Cyclist“.