We’ve been looking back on the life of the late Ron Webb, one of the most important men in the development of professional track racing and the construction of velodromes all over the World but Webb was also a rider and cut his teeth behind the big motors.

Englishman Pip Taylor was a close friend of Ron, who we recently paid tribute to in our pages. Among Ron’s effects Pip found the following essay about Motor-Paced racing which the Aussie, who was once fourth in the Worlds behind the big machines, penned.

The French used to call it ‘le demi-fond,’ in English we called it ‘the big motors’, ‘pace following’, ‘motor-pacing’ or ‘stayers.’

Intrepid riders on specially built machines with a small front wheel and reversed front forks so they could tuck in tight behind their leather-clad pacer whilst turning monster gear ratios.

At it’s best it’s a wonderful – if ecologically unsound – spectacle, especially on a big, old concrete bowl with the motors roaring and the big machines running at autobahn speed with crazy guys in silk fronted and wool backed jerseys tucked in behind them.

For a long time it was hugely popular across Europe and it still survives in Germany and to a lesser extent in Switzerland today, but in its popularity and big money lay the roots of its demise as a World championship discipline…

‘Bungs’ some call them, others ‘pay offs’ or simply ‘bribes,’ there was no way you could win without your pacer being well enough remunerated to ride for you.

But you never knew if he was going to until the Worlds final when for some reason (a big bung from another rider, perhaps) you kept hitting the roller because he was backing off when he should have been accelerating.

The UCI (and everyone else in track cycling) knew it was getting out of hand and so closed the book on the event as a Worlds discipline.

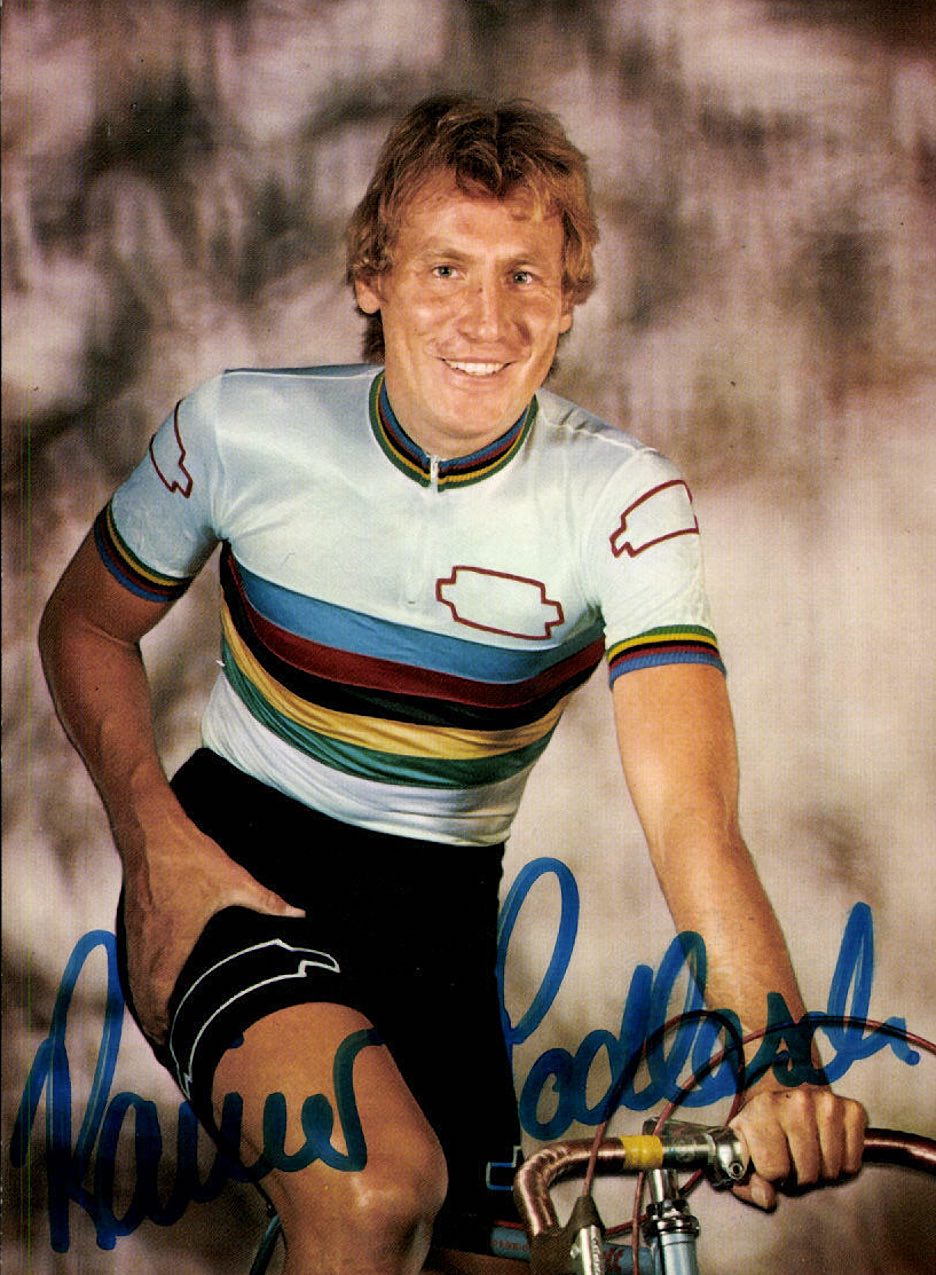

The last amateur Worlds for the event was held in 1992 and the last professional Worlds in 1994 with Germany’s Carsten Podlesch winning both races; he once explained a few years back to me that he was therefore “World Champion forever”.

* * *

By Ron Webb

I must first set an overall picture of the Big Motors (they compare with airplane motors); there’s BAC 2200cc, the Anzani-2200cc and the Meyer 2300cc – all heavy frames that are best suited with little or no wind.

It’s a fantastic feeling sprinting on the 500 metre Amsterdam Olympic Stadium in an attack, then maybe a third motor would attack you and round the track you would go, three abreast.

The stub exhausts flaming at night… the turbulence… not something I personally will ever forget.

But the world of motor pacing was not the best behind the scenes and though I still number a few pacers among friends, the majority are best forgotten.

Collusion seemed the state of affairs and if you found your pacer easing and then accelerating – with you hitting the roller and then chasing the roller – then you knew you had been sold out, but proving that was difficult, they all had excuses.

The motor-pacing scene was a pretty grubby affair; I remember the unwashed long-john combinations covered in oil stains, holes in the knees, generally in tatters and smelly – and that was just the wives!

One year Easter fell on the wrong end of April and it meant a long wait until the Dutch bike racing season started in May, so I decided to go to Paris for four or five weeks.

I could train every day on the beautiful Parc des Princes track and do some races out in other towns.

I booked myself in a grotty hotel at St. Cloud.

Climbing up the narrow staircase carrying my road bike was a bind but a good trade off, I thought, for living in a high upstairs back room with a view over the rooftops of Paris – surely this was a dream every young Anglo Saxon, from the four corners of the world?

The reality was not as I expected – an untidy, unclean musty room with the toilet two floors down (though one must respect French plumbing, because the sinks in the rooms were always the right height!)

Every night at 7.30 pm a man and a woman in the next tenement block began screaming at each other until 8.30 pm then as though it was choreographed the noise stopped dead – wonderful.

Then at 9.00 pm, down at ground level, the cats started.

By the time my stay in Paris was finished, I didn’t think well of the romantic idea of the rooftops of Paris.

Since then I have considered Hemingway a very dodgy author but when I was on my bike I was happy. Each morning and afternoon I went to Parc des Princess and I was in my element, the great attraction for me was that I had an arrangement to ride behind a famous pacer whose name was Pasquier.

Monsieur Pasquier was a small man with a shiny bald head, an extremely nice man, a gentleman of the old school.

I cannot remember his Christian name or if I ever knew it. I would never have used it; to me he was ‘Monsieur Pasquier’ and I addressed him accordingly.

Now, the great attraction of Monsieur Pasquier was that he had, as a stayer, what we followers called “Abri”.

Abri translates as “shelter” but in the stayer sport it was the skill of protecting the cyclist behind the motor from the slipstream.

There are some misconceptions when thinking of pace making. One might think a big fat person would be best at this task but just the opposite is true; the wind hitting the Michelin Man figure follows his outline like an aerofoil and hits the cyclist smack on the nose.

Being a clever dick, I sussed out very early in the game what made the best pacers. These were normal chaps, sometimes lean figures, but one who sat on the motorbike in the correct manner.

I remembered long ago in the Australian countryside, cars and trucks were fitted on the front of the bonnet with a plastic “V” three or four inches high. This plastic wedge directed the wind-and with it the flies, insects and locusts away from the windscreens, and it was very effective.

I observed that a pacer angled forward became a ‘wedge form’ to deflect the wind. The ‘vacuum’ caused behind a good pacer is obvious when you blow your nose and watch it go up the back of the pacer’s leathers!

Monsieur Pasquier had this gift. Fantastic, he was a small man but his body was like a wedge into the wind. Pasquier was the tops, riding behind him was as good as it gets.

One never looks down when riding behind a motor. Anything moving quickly mesmerises, and one becomes 100% reliant on the pacer. The skill is to ride as close to the roller as possible without touching. Looking at the pacer’s back to judge the distance instinctively, with Pasquier I used to look at the back of his neck then I was also able to see past him and be able to judge my own output.

If I could see the need to attack well ahead I would prepare myself for this – and I must quickly add that I would never blow my nose up the back of Monsieur Pasquier’s leathers.

However, as fantastic as Pasquier was, he had, for a pacer, a very serious handicap – he was allergic to motor fumes and as the race progressed he would be coughing from deep down in his lungs and his small body would move as he coughed.

His shoulders would heave and his head would roll and nod, at that time of my life I may well have been fearless, but I was quite apprehensive at times.

Once, in Amsterdam he was riding with Piazzali, at the end of the race his helpers had to lift him off his motor and he leaned against the motor bike, heaving and coughing and we were all in fear for him. It did look bad.

In Paris the other pacemakers who spent their afternoons in their garage style cabins, tinkering with their motors and waiting for the chance to charge someone for a training session were always moaning about Pasquier and that he was a danger on the track. But the annoying thing to them was that the riders would keep on and on about Pasquier’s ‘Abri.’

Pasquier would never accept money from me, not even for benzene.

He said; “You are young and Paris is expensive, you will have a need for your money” and he was right about that!

Soon, my stay in Paris came to an end and I headed back to Amsterdam. I’m not exactly a Francophile, my experiences were not always good… racing somewhere and then chasing the management for a week to get my contract money went against the grain. I’m best not suited for begging for my own money.

So, back to Holland where I suddenly realised that how much I missed having a laugh.People in the Netherlands have a great sense of humour and I had missed that in France.

Later that year, in December, I was racing at the Hallenstadion in Oerlikon, the indoor track in Zürich.

Also on the card was the French stayer champion, Roger Godeau and as we sat on the infield benches waiting for the sprinters to stop prancing around on the track, Godeau, leaned over and said “Did you hear about Pasquier?”

I say ‘no, I did not hear anything about Monsieur Pasquier and I am very sorry to hear bad news for he was a nice old gentleman’.

“Oh no,” says Godeau, “he’s not dead, not yet anyway…” and the story unfolded that the other pacers in Paris were so fed up with hearing how good Pasquier is – though I’d reckon it was more a case of thinking what would happen to them and their riders if Pasquier crashed at 80kph, resulting in mayhem – that the pacers pressurised the Federation to only issue pacers’ licences after a medical examination.

The medicals were duly held and Pasquier was the only one who passed!

* * *

A great tale, well told!

In closing Pip explains:

“Pasquier’s Christian name was Arthur, not to be confused with Gustav Pasquier who came 8th in the 1903 Tour de France.

“Arthur Pasquier was born in March 1883 and died at the age of 80 in December 1963, he retired after Roger Godeau’s final race at Parc des Princes in 1961.

“Assuming Ron was in Paris in 1956/57 that would have made Pasquier 74 years old when this was written about him.”

With thanks to Pip Taylor for this gem.