Regular VeloVeritas reader, Pip Taylor was a ‘runner’ at two of the early editions of the SKOL Six Day races in London, he’s kindly shared his recollections with us.

* * *

By Pip Taylor

I fell in love with Six Day track racing having been taken to the Earls Court Bike Show by my Father in 1967.

The sight of continental professionals riding on a 140 metre “wall of death” was intoxicating.

I just wanted to ride on that track and to be a Six Day rider.

I raced my Chiltern RC club-mates along Slough High Street, Madison slinging each other going home from club nights.

One way for young riders to learn about the real world of Six Day track cycling was to be a runner for one of the professional teams riding in a Six Day.

The term ‘runner’ in professional track cycling terms is used to describe a rider or a team’s helper.

A runner works alongside a team’s mechanic and soigneur and does all the menial jobs.

Here are a few reflections on my experience as a runner in the early 1970’s at the SKOL 6 Day.

It was a different age…

* * *

1. Engagement

To become a runner you either made an arrangement with a professional rider-friend or you turned up at the stadium on day one and waited around to meet the arriving riders.

You helped them unload their equipment and kit and move it to the track centre and to the riders sleeping rooms under the seating at Wembley.

The elite Six Day riders would organise professional support in advance.

The British parings would often rely on volunteers such as Reading trackie Gordon Stemp, or Bill Horne in the case of Tony Gowland.

In the process of settling the riders in you would offer your services as a runner.

I cannot recall any negotiation regarding payment or expenses, at least in my case.

I was a runner twice, once in 1971 and again in 1972.

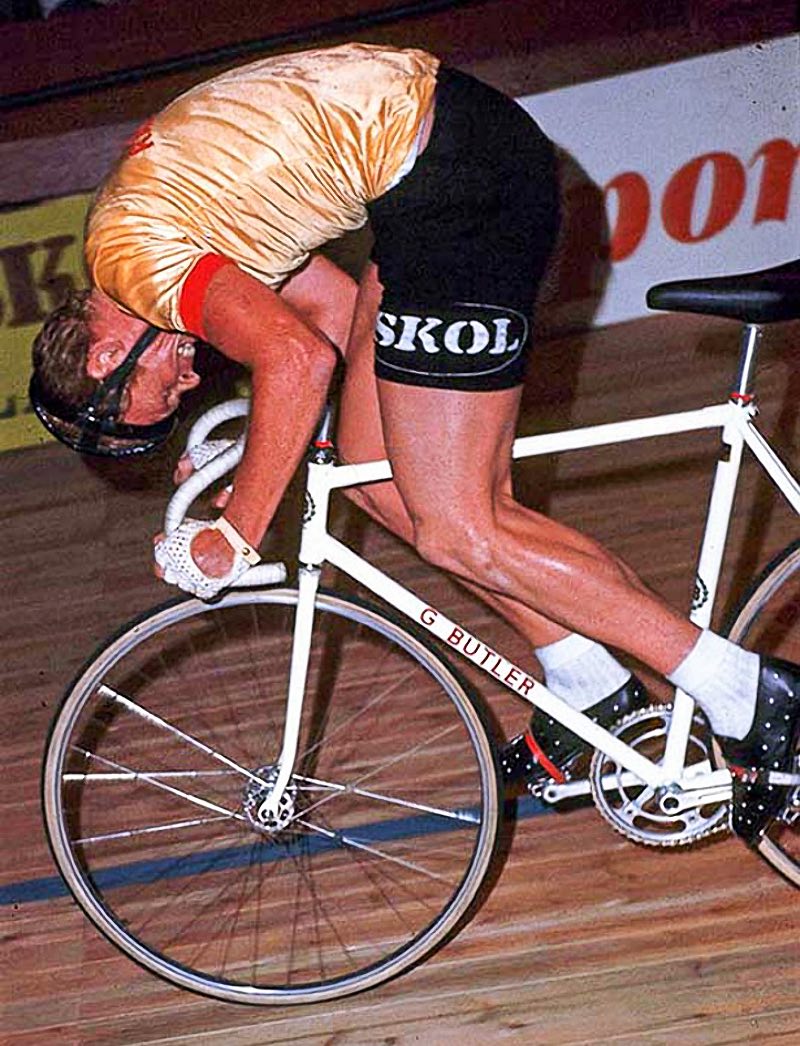

I was an 18 years old first year senior and one of a group of amateurs who rode down at Calshot – on the old Wembley Six Day track which is housed in a former seaplane hanger – in sessions coached by Six Day promoter Ron Webb (before he became a world class velodrome architect) and bike shop owner John Pratt who ran Geoffrey Butlers in Croydon.

These sessions were by invitation and involved top track professionals such as Tony Gowland, Trevor Bull, UK Champions such as Roy Cox and often visiting Aussie track internationals such as Murray Hall, Tom Moloney and also World Sprint Champion John Nicholson.

These became try-out sessions for selection for the SKOL Six Day amateur support races and the full professional Six Day.

I often rode with my Chiltern RC team-mate Steve Snowling who was very good on a board track and also went on to be a top professional mechanic on the continent.

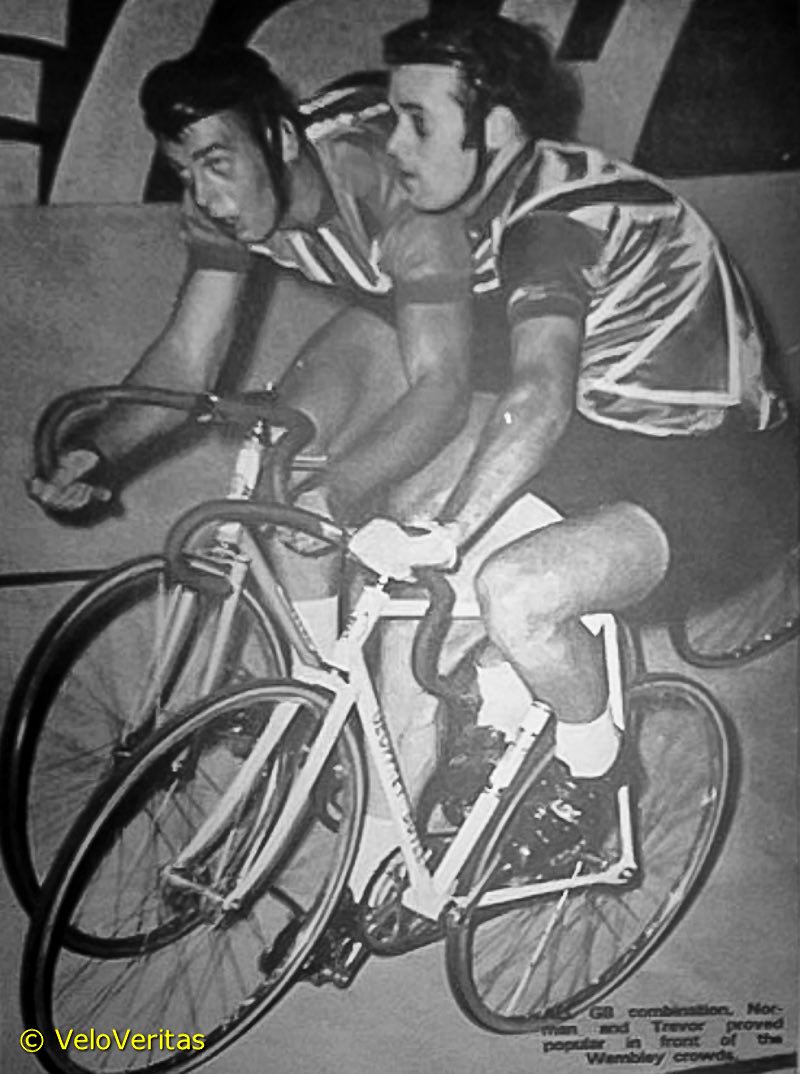

I knew Birmingham Carlton professional Trevor Bull and Tony Gowland from those sessions.

Trevor stayed at my parent’s home in Slough when he rode a local professional road race.

I asked him if he needed a runner and an arrangement was made and at that time I did not know who he would be partnered with.

* * *

2. Arrival

Steve Snowling and I were told to turn up at the back door of Wembley Arena (then known as the Empire Pool Wembley). The first thing I remember was the smell.

No, not the lovely Siberian Pine smell of the Herbert Schurmann track but a more earthy organic smell – the legacy from the Horse of the Year Show held in the arena. There were piles of it next to the temporary stables alongside the rider’s car park.

Inside the door and to the right was a kitchen and a canteen that became the riders’ canteen for the Six Day.

Dutch Chef Jan Hiele ran this operation and Steve who had not made a runners arrangement was seconded to the kitchen to help scary chef Jan (more on him later).

We wandered in with no security checks or accreditation in those days and to see the top professional arriving was very exciting; the team cars, the equipment, and these ‘Gods’ of Six Day cycling. I was very nervous.

Trevor was riding with another top GB trackie, Reg Barnett whom I did not know well but had idolised him when seeing race him at Herne Hill.

It was perhaps cruel of the promoter to pair GB riders together in the SKOL Six Day, than with a top continental ‘taxi driver’ to mentor them.

Finding a cabin that had not already been taken by the ‘Blue Train’ – the group of top riders who ruled the roost- I moved the equipment into the track centre and hung the spare wheels on the rack above the cabin and bikes under a table behind the cabin.

We were about as far as you could be from the finish line and the Post/Sercu cabin.

I was down to ride the amateur Omnium on the Saturday afternoon so was doubly nervous and had not even considered where I would be sleeping or what the food arrangements might be.

Luckily Steve sorted out the food for us both and he had brought a camp bed and sleeping bag for himself, but I had not thought of the camp bed, just a sleeping bag.

Other runners and the soigneurs set up their rider’s rooms and cabins.

I set up three camp beds, brought by the Trevor, Hugh Porter and Reg to a dark and dingy room under the seating inside the arena. They were lined up pretty close together to accommodate three riders in one small room.

Hugh was riding with Klaus Bugdahl, so they had their own support crew and trackside cabin.

In those days – unlike the Six Day Series – rider pairings tended to share the same cabin throughout the event.

* * *

3. A Strange Request?

That first night, I got what I thought was a strange request from Hugh Porter.

He said could I get him two empty milk bottles?

With Steve’s help we found some and I took them to the room under the arena.

Hugh said after the racing each night he would be too tired to walk to the bathroom at the end of the arena to go to the toilet so he would like to use the milk bottles.

He put them on the floor between Trevor and his camp beds…

I went in to wake them up on the Saturday morning.

Trevor looked a bit perplexed and I asked him if he was OK.

He said he had a strange dream that night which involved hot rain.

I looked down and saw that the two milk bottles were both full and overflowing!

* * *

4. Sleeping

As mentioned, rather naively, I had not prepared a camp bed to sleep on. I decide the only place for me to sleep on night one was my rider’s cabin track side.

This was not a great idea especially when I was riding the amateur Omnium that following afternoon (and sorry to Len Cawley, my Whitewebbs London B teammate).

The cabin was too short to fully lay out and it was hard.

The arena lighting although dimmed a bit was still on and around 05:00 am in the morning the cleaners came in to sweep the seating and aisles in the stadium.

I was woken by the sound of SKOL Lager and Coke cans tumbling down the Wembley Arena seating tiers.

Plan B involved my Dad bringing up a camp bed the next night but after riding the Omnium and ‘running’ all night I could have slept anywhere.

* * *

5. A Runner’s Day

As long as there was no matinee Saturday or Sunday racing sessions you were free to do what you wanted until the late afternoon.

I would polish the alloy parts on the bikes, but for some reason there was no compulsion to stray far from the arena.

I had my track bike and kit but did not dare to ask to get up on the track.

I sat by the cabin and watched top Belgian mechanic Charlie Loedewijkx truing and preparing wheels by revolving them over a methylated spirit flame to soften the layers of shellac varnish – which was the tubular tyres were bonded to the rim with – before attaching a new Continental tubular.

He would always have a bottle of Cointreau on his work bench.

He was a master and a very nice man.

You generally didn’t see the riders much after breakfast until mid-afternoon and around 4-5 pm the riders ate in the canteen.

That’s where I first encountered Jan Heile.

The riders sat in the canteen and as a runner you ordered their food and waited table. The ‘Blue Train’ sat on one table and the Brits and Aussies on another. Some riders sat alone.

I ordered steak and rice for Trevor and Reg but and asked the chef Jan if the steak could be cooked a little more, Jan asked me which rider was this for, “junga”?

I told him for a British pairing of Trevor and Reg, he said something sounding rude in Dutch, waved his arms and a big knife about and we got steak cooked as Jan liked to cook it!

Steve Snowling looked on shaking his head from the back of the kitchen.

Funnily I got a completely different reaction from Jan Heile when asking for ‘special food’ for Leo Duyndam and Gerben Kartsens in 1972.

My food as their runner was better too, somehow?

In 1971 the weather was good and sunny so some riders sat outside the back door of the arena in the sun.

One day I noticed a rider’s car hoisted into the air on a fork lift truck with no wheels attached. I guess they had got bored.

I was told there were other ‘visiting distractions’ in the afternoons for some of the riders but I didn’t actually witness those goings on.

Prior to the start of racing you got the bikes and spare wheels ready, did tyre pressures and spanner checked the kit.

You checked the standings and the programme to see when the Derny races were, which of your riders were involved in what race.

During the racing you pushed your rider off and slowed them with an arm to a stop them by the cabin, put the bike on a stand and changed their jerseys and undershirts, hanging them up to dry.

The golden rule being never to put anything especially the towels on the seat of the cabin where the rider sat (and where I had slept on night one!).

Trev and Reg did not have a mechanic or a soigneur so we managed pretty much as a closed team unless they were involved in a crash which unfortunately happened a few times.

One of the other British mechanics would appear and check over the bikes, and so would I. They got patched up by the local St Johns ambulance team.

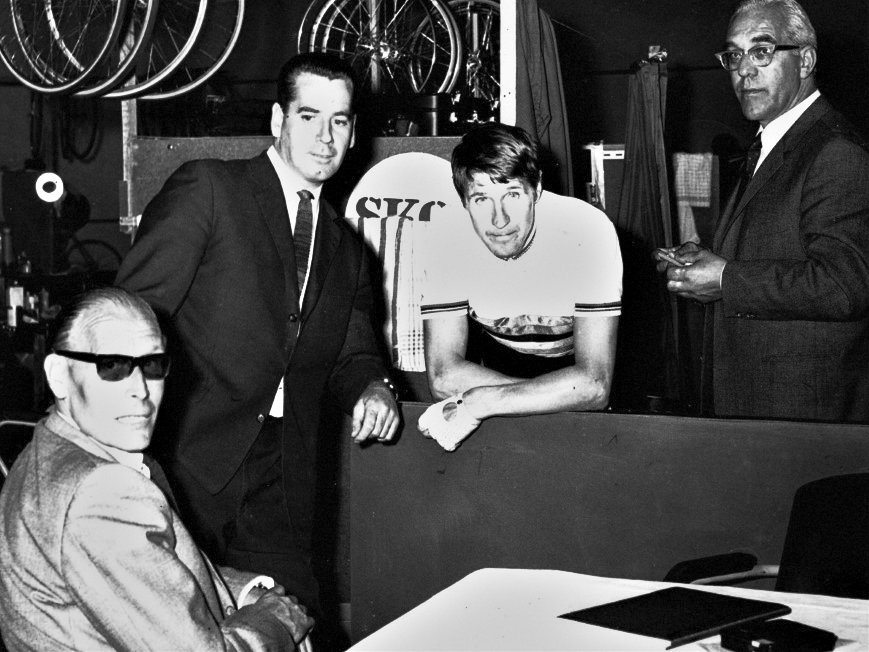

In the hour before the start of racing around 6pm you saw VIP’s (celebs as we would now call them) being shown the riders cabins and introduced to the riders by Ron Webb and other officials.

I walked around the side of our cabin and bumped into a very tall man, whom I then recognised as the actor Jon Pertwee (‘Doctor Who’ no less).

I also saw Keith Moon, Supermodel Twiggy, TV celeb Kathy McGowan and was told the Rolling Stones were in the house but sitting up in the gods rather than the track centre.

Once racing had started you did whatever you could to help your riders in what was now a modern format but still an old style Six Day where one team rider had to be on the track at all times, even just rolling around between races so the public could see them.

I cannot remember much about the racing each night but by the end of it standing all night on my “racers” legs, I was shattered.

* * *

Jump to Part Two where Pip Taylor covers his time working at the 1972 race.