Cycling is full of ‘what ifs.’

‘What if’ the Second World War hadn’t stolen some of Fausto Coppi’s best years?

‘What if’ Greg Lemond’s brother-in-law hadn’t shot the Tour winner and World Champion when they were out turkey shooting; denying him a wedge of his prime?

And ‘what if’ the UCI hadn’t changed the rules governing bicycle design after our own Graeme Obree shattered Francesco Moser’s world hour record on ‘Old Faithful,’ a ‘home-made’ machine which infuriated the UCI and was diametrically opposed to Eddy Merck’s 1972 jewel of a Colnago hour bike and Moser’s futuristic 1984 machine?

Then it would be entirely feasible that South Africa’s Wimpie van der Merwe with a 53 plus kilometre ride would have succeeded Obree’s 52.713 kilometre ride and not Miguel Indurain with his 53.040 kilometres.

With Jim Gladwell soon to go after the Scottish Hour – before them HUUB boys in the Andes – we thought you might like to hear Wimpie’s tale.

“My hour record attempt took place in Bordeaux at the Velodrome du Lac on June 21, 1994.

“I knew I could break Graham Obree’s record if I did 53 kilometres; he’d ridden 52.713 on April 27th of that year.

“In my preparation and with the calculations made by the technical support team from Lotus and Aerodyne it was determined that if I could deliver 420 W for the hour it would be possible.

“I crunched out 427 W for 65 mins in my trial workouts.

“The aerodynamicist from Lotus, Richard Hill worked with Chris Boardman, set me up in the wind tunnel.

“Some 24 Hours before the attempt the UCI came to measure the bike to see if it was legal.

“What we didn’t know was that they had changed the rule of how a ‘legal’ bike should look like, in reaction to Obree’s ‘washing machine’ bike two weeks before my attempt.

“They did not inform our team.”

“My set-up was already established and since the frame was a monocoque structure, nothing could be changed to fulfil the demands of the required alteration.

“They demanded that the saddle had to move back 5 cm and it couldn’t – the saddle support on which I had to sit was about 7 cm. We had to butcher the saddle and this gave me only 2 cm to sit on, which made riding the bike impossible.

“This hour was the most excruciating, self-inflicted pain I have ever experienced, but I tried more than my best under the circumstances.

“The result eventually was a South African 4,000 m Elite and veteran record (4:50 min) and a South African One Hour record of 45.541 km.

“The experience was sobering; I quickly saw that the press that hails you are same as those that crucify you.”

Is that still the RSA national record?

“No, the current South African record holder is Gert Fouché who established himself as world record holder in his 35-39 age group – we can be proud of his 51.599 kilometre achieved at Aguascalientes in August 2019.

“I’m lying eighth in the world in my age category.

“It’s still on my bucket list to tame this Hour beast.

“The Hour is not called the ‘hour of truth’ for nothing.

“It is a career ending effort for most that try it.”

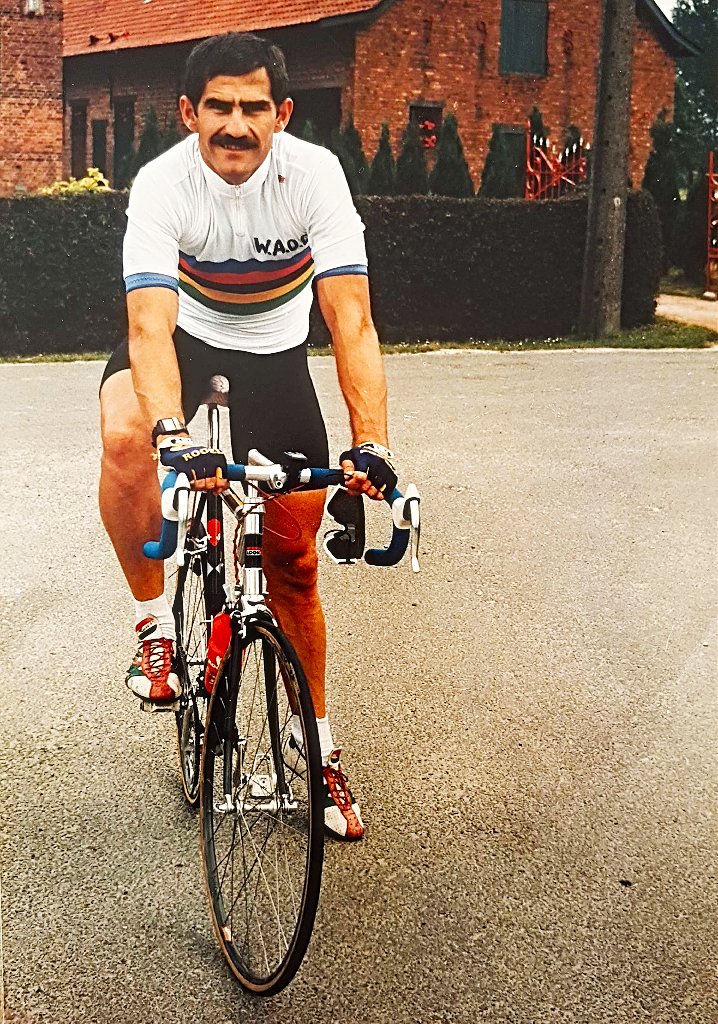

So who is this guy that none of us heard of on the international stage but who was turning out wattages that could have won him an elite professional time trial at the highest level?

Why choose ‘the impossible hour?’

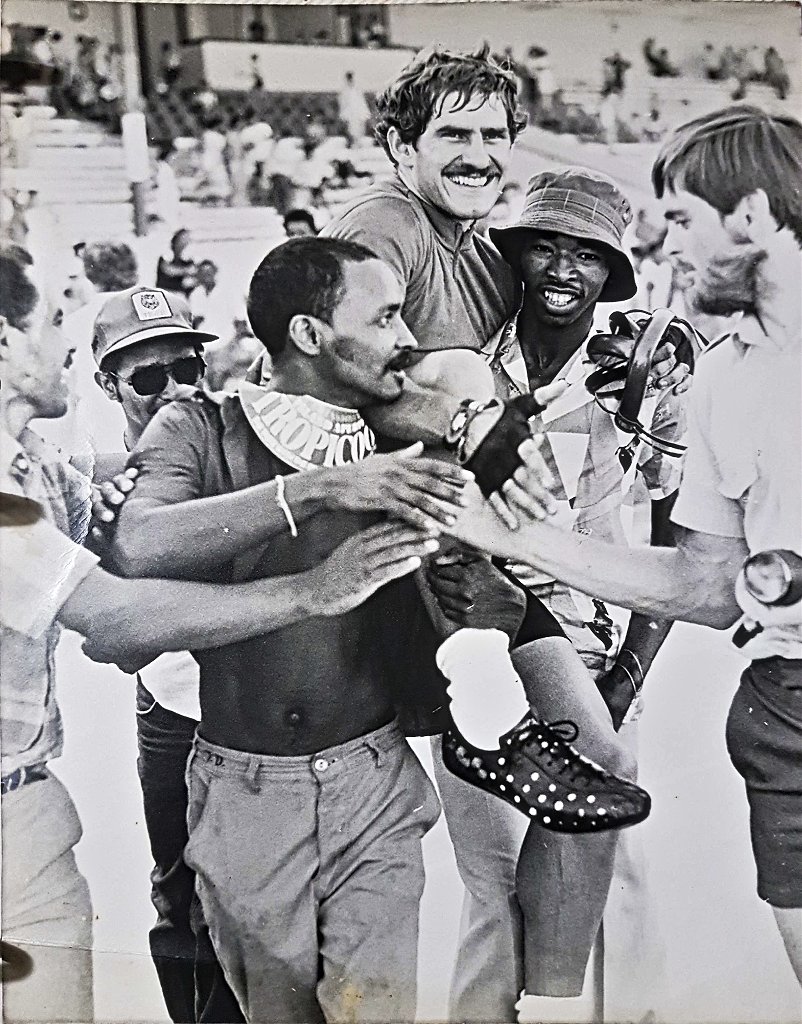

“What do you do when the RSA [Republic of South Africa) national selectors inform you that you and other senior riders will no longer be chosen for the national cycling teams because they are focusing on a younger generation for future Olympic Games?

“When your country is readmitted to international sport in 1992 after being denied since 1960 because of the ‘apartheid ban,’ you’re at your peak, but cannot select yourself to represent your country, how do you then compete against the world’s best?

“You take them head on by breaking their world records, no matter when the records were set.

“Instead of waiting for opportunities to come, you create them.”

But where did you come from and what had you done on the bike prior to being able to pump 400 watts for an hour?

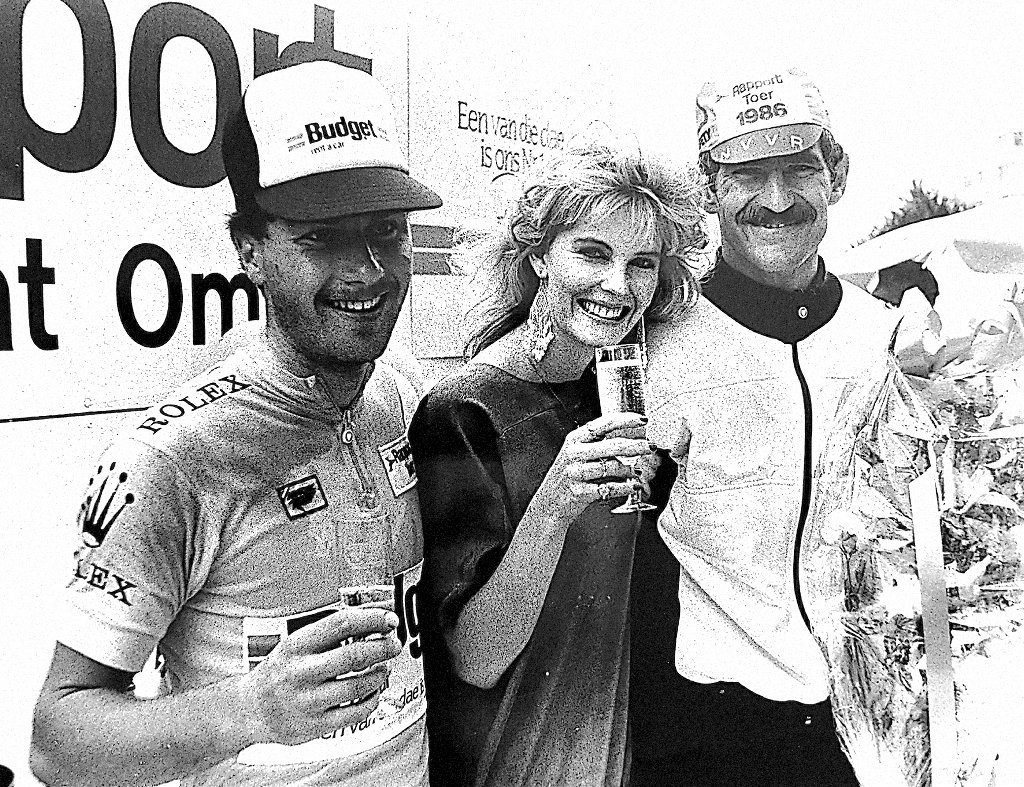

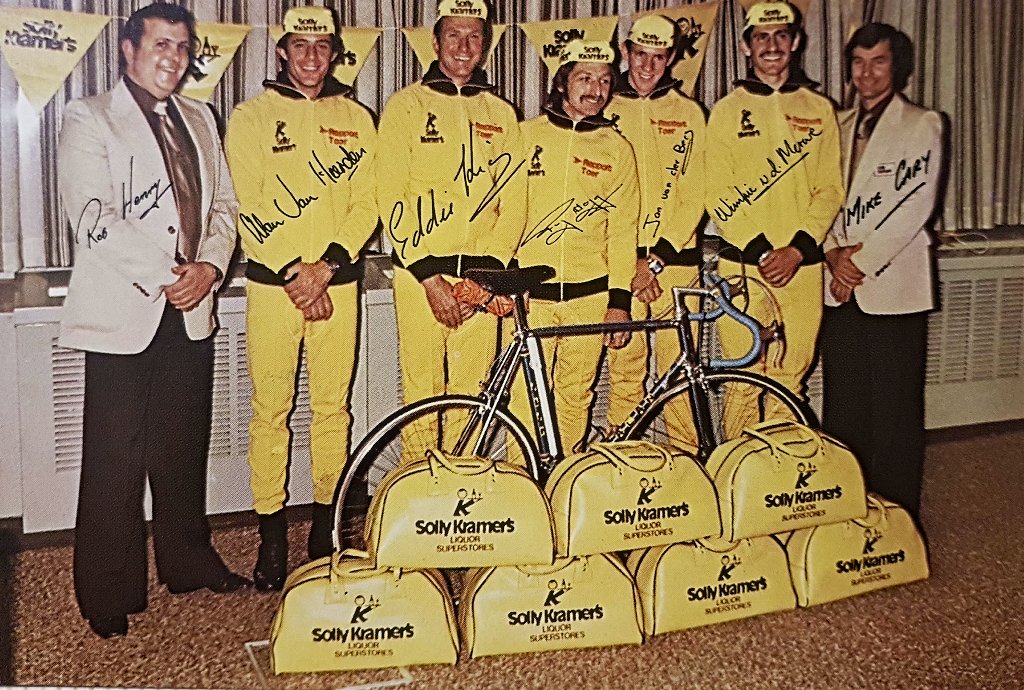

“I got into cycling originally by riding back and forward to school, then in 1973 the Rapport Tour was launched, a multi-stage race from Cape Town to Johannesburg.

“This captured the imagination of me and a group of guys I was at school with and we decided to ride the route – obviously not the race but cycle touring the parcours it described.

“That was the start, I went on to ride the Rapport Tour nine times and win the South African Road race Championships three times.

“But as I said, in 1992 when the world-wide ban on South African international sport was lifted the powers that be decided that they were going to concentrate on young riders for two Olympics hence.

“It left me high and dry, that’s why I turned to record breaking.

“I trained for six months for that record bid, most of it indoors on a turbo because it was our winter and I was getting the numbers.”

Why not go for it again after the unsuccessful attempt with a new bike and the knowledge you’d gleaned?

“The press weren’t kind to me after the attempt and the sponsors were disillusioned by what had happened so it would have been very difficult to resurrect things.”

And then you turned to recumbent records?

“I remember speaking to the famous US coach, Eddie Borysewicz – and he told me a rider should play to his strengths, not waste his time riding events which didn’t suit him.

“I’m not a light rider but even at 62 years-of-age I can still produce 380 watts for an hour so if you put an engine like mine inside a streamlined fairing it’s pretty effective.

“Knowing my ‘hour’ background, a couple of engineers approached me about a project involving a streamlined recumbent bicycle.

“I used that to set the fastest-ever time for the Argus Tour circuit in South Africa; in 1993 I covered the 105 kilometre parcours in 02:16:40, averaging 46.1 kph.

“From there we created ‘Project Synthesis;’ I worked with Tim Noakes who’s a physiologist and doctor and a team with whom we created aerodynamic machines which took me to RSA, African Continent and world records for HPV (human powered vehicles).

“I list the world records I set along the way:

* 4,000 m flying start – 3 min 22.388 sec

* 4,000 m on four occasions, best – 3 min 33 sec

* 10,000 m on four occasions, best – 8 min 39 sec

* 12 hours – 566.974 km

* 24 hours on two occasions – 904.887 km

* 1,000 km – 27 hr 43 min 48 sec.

“These records were all set under the auspices of the IHPVA – International Human Powered Vehicles Association.”

You rode 1,000 K on a recumbent?

“Yes, and I do ultra-distance Audax events on a ‘normal’ machine:

* 2015 Paris-Brest-Paris (1,230 km)

* 2016 Cape 1,000 (1,036 km)

* 2016 Mille Miglia (1,600 km)

* 2017 London Edinburgh London (1,400 km)

* 2019 Cape 1,000 (1,042 km).”

With all that, is there anything left on the Wimpie ‘bucket list?’

“I’d love a crack at the world hour record for my age group but it’s not easy to get sponsorship for an attempt.”

We’re sure that if it’s at all possible, Wimpie will organise it – and did we mention his ‘Everesting?