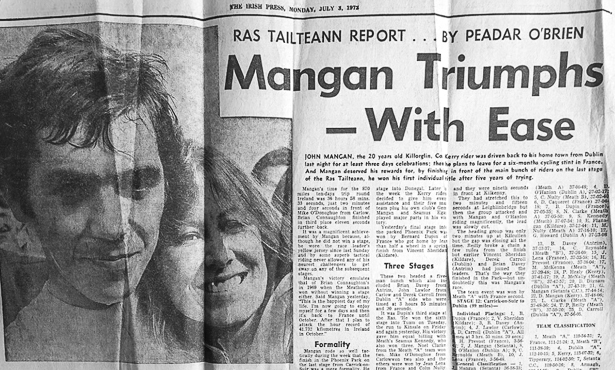

‘Mangan steals show’ or ‘Ras title for Mangan’ nice enough headlines but there’s just something about French that rings that little bit better, ‘John Mangan en solitaire,’ or ‘Mangan brillant vainquer a Cagnes.’

‘Mangan steals show’ or ‘Ras title for Mangan’ nice enough headlines but there’s just something about French that rings that little bit better, ‘John Mangan en solitaire,’ or ‘Mangan brillant vainquer a Cagnes.’

But not just Cagnes – Fougeres, Cancale, Landihen, La Gouesniere, Loudeas, Trebry, Evry, Saint-Ouen-la-Rouerie, Ploemeur, Montauban, Rennes … I could go on.

John Mangan won 156 continental races not to mention a raft of races in his native Ireland before he headed for France and huge success.

Such was his strength both on and of the bike that for a decade he was head of the ‘Brittany Mafia’, the group of riders which controlled racing in the West France racing Heartland.

He would tell me; ‘I think that in all the years I was there we only let two wins slip away from us.’

But he wasn’t just a ‘crit king,’ he thrived in stage races and his trophy wall displays silverware from far-from-flat Spanish races.

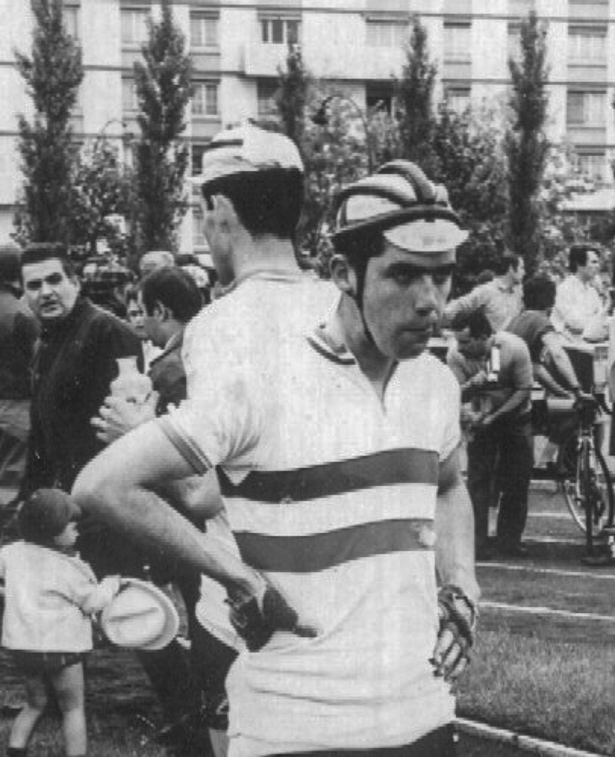

I first came across him on a racing trip to Lorient in 1976 when we went to watch a criterium in a small town whose name I’ve long forgotten.

He was burnt almost black with the sun, stocky, intense, a man with a real aura around him, even as a naive youth I could recognise star quality when I saw it.

And it wasn’t just me who thought so, in William Fotheringham’s book, ‘Bernard Hinault and the Fall and Rise of French Cycling’ when looking back at the moment when Hinault’s talent really became apparent;

“The other significant win came at the end of the season in the Grand Elan Breton, a time trial over sixty kilometres open to all categories, which Hinault won at an average speed of 41.7 kilometres per hour ahead of the Irish cyclist John Mangan.

“Mangan was then in the first flush of youth, and his career among the amateurs in Brittany would last into the 1980’s; for his even younger rival, this result at the age of seventeen meant one thing; he had a huge engine.”

When Bernard Hinault uses you as a yardstick then you have to be special.

Monsieur Mangan is now back in his native Ireland, residing near the village of Killorglin down in County Kerry where he farms and has a ‘hunting, shooting, fishing business.’

Killorglin is famed as the venue for one of Ireland’s oldest fairs, ‘The Puck Fair.’

The locals go up into the hills, capture one of the feral goats and then, as the village’s website expresses it;

‘The king of Puck Fair, a chosen mountain goat is borne in triumph and enthroned for two days.

Why is a goat the king of the fair?

Local stories tell that a stampeding herd of mountain goats warned the locals of the invasion by the Cromwellian forces!’

Sadly, I missed the fair but was in time for the annual ‘Rose’ festival in nearby Tralee where lassies of Irish origin from all over the world compete to be the ‘Rose’ – the whole affair is televised over several nights and viewing figures are huge.

As well as the obligatory evening dresses and interviews, the girls have to do a ‘turn’ – this could be an Irish folk dance or sing a song.

However, one lass chose to cook an omelette as her ‘turn’ – I missed that one.

The ‘Puck Fair’ and ‘Rose of Tralee’ both go in the ‘Only in Ireland’ file but despite the beautiful rural Irish surroundings to Mangan’s house, it’s built in the style of a Normandy Chateau with it’s double curved hewn stone frontage – and huge collection of wine and spirits.

His taste for fine French architecture and wine picked up during all those days and years spent in La Belle France.

Le Patron and I sat down on a sunny morning after a night of sampling the contents of said wine cellar to discuss his reign as ‘King of Brittany Bike Racing.’

How did it all start, John?

“I used to race home from school on my bike and I could always beat the other fellows.

“Then when I was at college I used to ride to the football with another fellow on the handlebars and I could still best the other guys.

“I saw a stage of the Ràs in 1967 in Killarney and that sparked my interest.

“I won my first race as a schoolboy and then when I moved up to Dublin for my apprenticeship there was a good bit of racing up there – Phoenix Park was a popular venue.”

Why France?

“I was with the Irish team for the Grand Prix Humanite in Le Havre; it was a organised by the FSGT (Federation Sportive et Gymnique du Travail) which is a Socialist federation.

“I rode a criterium in Paris too and it gave me a taste for it.

“I went back to Rennes for six or seven weeks on holiday to race in 1971, that was the year I was second in the Ràs after crashing whilst in yellow.

“For 1972 I was based in Rennes having started the season down in Nice but I came home for the Ràs – and won it.

“For 1973 I moved to Ploubalay where I stayed for the rest of the years that I was in France.

“The locals didn’t have a lot of time for me to start with but when I started winning that changed; 30 years after I rode my last race in 1984 and moved home the Mayor of Ploubalay held a civic reception for me – which was a really nice gesture.”

Why Rennes?

“I drove my Morris Minor off the ferry and a little down the road I passed a group of cyclists, stopped and chatted to them and they said Rennes would be a good place to base myself.

“When I got to Rennes I met a policeman and he took me to a bike shop, they were really helpful and introduced me to the Velo Club Rennes – there was nothing pre-arranged.”

Can you remember your first race?

“Yes, it was near Rennes and Jean Paul (JP) Maho won it, I was sixth.

“At the start of the 1972 season I got a ride with the Vitfrance team and we had a couple of successful months at the start of the season racing down around Nice – and I was with them again for ’73.”

How do you break into the ‘Mafia.’

“In 1974 in the criteriums I would often lap the field so they didn’t have much choice but to let me in!

“I was always good with figures so I was the man who divvied up the money.

“I used to have the notebook with every franc which went to every rider during my time there but I’ve mislaid it somewhere along the way.”

Remind us of your statistics, John.

“I rode somewhere between 1100 and 1200 races in the dozen years I was there, with 156 wins – most of them on my own because those French boys could all sprint!

“I won on power, if it was a draggy parcours then I would use a bigger gear than the rest to get clear, even in Spain I could ride the long, not-so-steep cols on pure power.

“And the longer the race the better, that’s one of my regrets about the politics preventing me from turning pro – when the distance went over 200 K I really came into my own.

“There was one month where I raced 28 days; there was no social life – sleep, eat, drive, race…

“By September you’d made your money for the year and eased up on the frequency of racing – down to three starts each week.

“I can remember racing five days on the trot and never finishing lower than second.”

And how about the Mercedes?

“In ’74 I was making good money – I suppose it must have been intimidating for the opposition lads arriving in their parents’ Citroen?

“When I left Killorglin to pursue the bike in France folks were saying that I was crazy, I had a good trade and there was no way I could make that sort of money on a bike.

“But as the years passed their opinion on that changed!”

Tell us about the ’72 Olympic adventure, John.

“I’d won the Ràs that year but Irish Cycling was divided at that time with the UCI recognising Northern Ireland Cycling Federation and the Irish Cycling Federation in the south but the National Cycling Association, which organised the Ràs was excluded from the Olympics.

“We decided to make a statement about this and decided we’d join in the race to make our protest; we hid in woods outside Munich with the intention of getting involved.

“We waited and waited but the race had been cancelled – it was the year of the atrocity with the Israeli team.

“The race was held the next day and some of our lads infiltrated the start causing the race to be delayed.

“Once the race started we burst out of the woods where we were hiding and joined the peloton. Eventually I was taken out of the race by a police motor bike and arrested – but we’d made our point.

“The police were good with us though, they gave us tea and sandwiches and we were allowed to go after the race finished.”

In an article in the Irish Independent in 2000 the protest is noted as being one of the factors which lead to integration of the various Irish Federations and Irish athletes acceptance into the Olympics.

Who do you remember as the riders you respected as opposition?

“Yves Ravaleu was an ex-professional who’d ridden the Tour, he’d been with Pelforth, Sonolor, Hoover, Mobel Marki and Gan but the pro life, ‘out of a suitcase’ wasn’t his thing.

“Alain Nogues was another, he’d ridden the Tour with Gitane and Sonolor and was a very strong rider but didn’t like being away from home.

“JP Maho, who I mentioned won the first race I rode was another; he had a wife and kids and didn’t like to ride outside of Brittany and Normandie.”

Check out Part Two of John’s interview where he tells us about drinking with Luis Ocana, the politics which hindered him turning pro, and the Irish Hour Record.