With the London Track Worlds fading into the distance as the classics season gets underway, we thought we’d run a few pieces which harp back to the ‘golden days’ of pursuiting – when all the participants didn’t ‘look the same’ and 5,000 metres was the blue riband distance for the professional greats.

Cycle Sport magazine run an article a few months ago, ‘The 25 Most Stylish Riders of all Time’ – Giovanni Battaglin, Roger De Vlaeminck, Francesco Moser, all fair enough.

But Tafi? Lizzie Armitstead? Cancellara?

And there were some glaring omissions, Tom Simpson, Ferdi Bracke, Ole Ritter and – Roy Schuiten.

In 1971 the big blond Dutchman took silver in The Netherlands amateur pursuit championships, a year later it was gold and there was a third place in the amateur Grand Prix des Nations.

He retained his Netherlands amateur title in 1973 and took bronze at The Worlds in the same discipline.

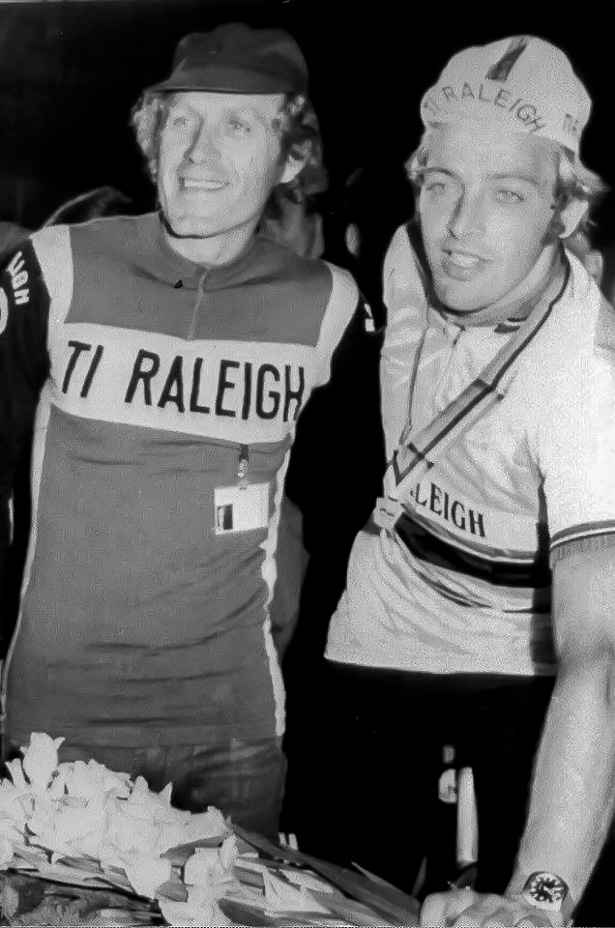

But it was 1974 when he truly exploded onto the scene, winning the Olympia Tour in Holland and the Milk Race as an amateur before turning pro for the mighty TI-Raleigh team.

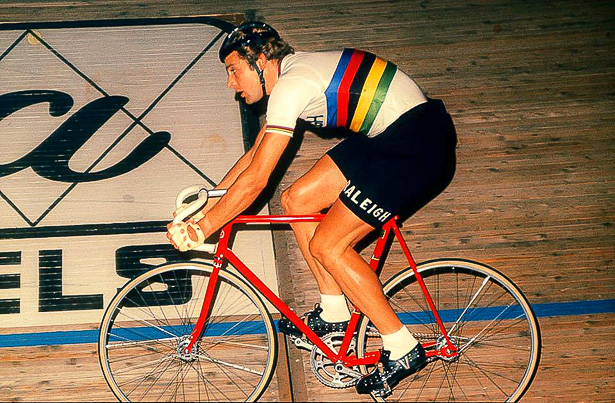

He won the World Professional Pursuit Championship, the Grand Prix des Nations and the Baracchi Trophy with Francesco Moser – a fabulous debut.

The following season his meteoric progress continued with another world pro pursuit title, the GP Frankfurt, the GP des Nations, the GP Lugano TT. The world was at his feet and we held our breath as Schuiten boarded a plane for Mexico to attack Merck’s Hour Record.

And things were never the same again…

The record attempt was a disaster; despite great form going into the attempt and Raleigh’s ace mechanic Jan Le Grand having built him a super light gem of a machine.

He got up on the track three times in pursuit of the record but at no time did he manage to match Merckx’s pace – albeit the Belgian did start at a prodigious rate.

TI Raleigh manager, Peter Post was a man who abhorred failure and his already deteriorating relationship with Schuiten was over.

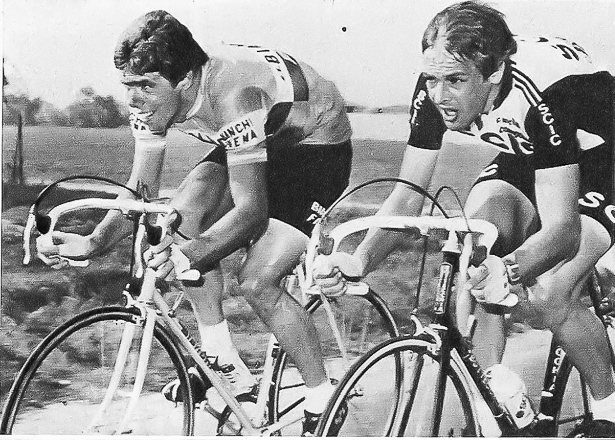

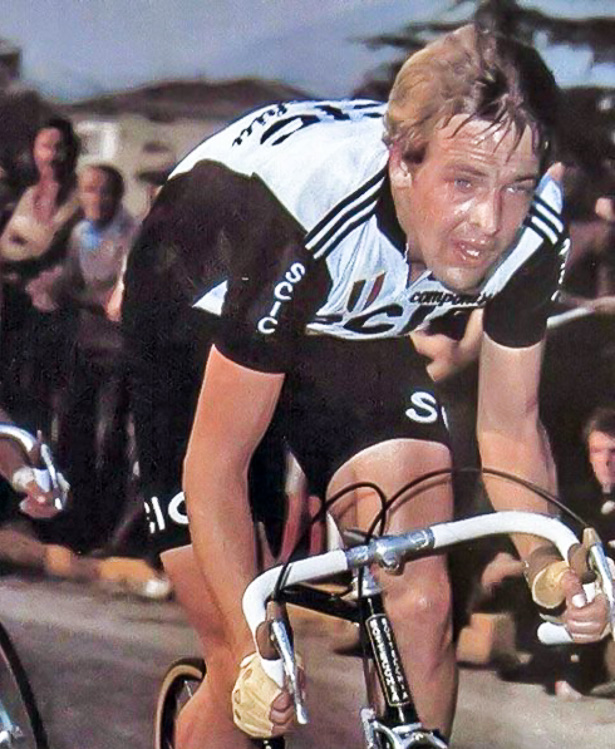

Schuiten headed off to France to Lejeune – the team who bought out the last year of his TI Raleigh contract – then to Italy and SCiC and whilst there were other big wins, he was never quite the same rider again.

He was second in the Worlds pro pursuit, Nations and Baracchi in 1976 with a win in the Tour of the Med the highlight.

In his second year with the French team there was a win in the TT stage at Dunkerque, beating Thurau but only fourth in The Baracchi.

With SCiC in 1978 he was again second in the Worlds pursuit, this time behind Braun and won the Baracchi with Norwegian powerhouse, Knut Knudsen.

In 1979 he won the GP Forli TT and was fourth in the Nations, but his best was behind him.

The name on the jersey was Inoxpran for 1980, Kotler in ’81; his last pro year was with the Spanish Kelme team in 1982.

He had a brief tenure as DS with PDM in 1986 and then opened a restaurant in Portugal, where lived until September 2006 when he died tragically young at just 55 years old from a stomach haemorrhage in Praia de Carvoeiro.

We caught up with Schuiten’s son, Rob to ask about his father, surely one of the most elegant men ever to grace a bicycle.

Rob was born as his father’s career wound down so never got the chance to see him at his brilliant best on the track or against the watch but he collects memorabilia from his father’s career and is always on the lookout for trophies, equipment and photos from his father’s ‘golden years.’

“Two years ago I met an old friend of my father’s; he had a box of treasure – trophies, ribbons, medals, sashes from my father’s career.

“My father wasn’t a man to collect stuff like that; when he was an amateur he didn’t pay much attention to that side of things and it was my late grandfather who used to look after the trophies.

“He’s the only rider ever to win the Olympia Tour and Milk Race in the same season.”

But Schuiten’s pro career nearly didn’t happen; his father was involved in a fatal car accident in 1973 and the young track star quit racing to help his mother look after the family off licence.

Rob explains;

“Yes, he took a year out to help run the family liquor store with my grandmother after my grandfather died but the national coaches, Harry Jansen and Frans Maan talked him back into getting on his bike.”

Schuiten’s 1974 pro debut was stunning, as Rob says;

“His first year was his best – there were The Worlds, The Nations, The Baracchi on top of his amateur successes.”

His success against the watch and mano a mano on the track give a clue to his character, a man who could be fiercely independent; Roy relates an anecdote which illustrates this part of his nature;

“He rode the big criterium at Chaam but became so fed up with being told who would do what and when in the race – and who would win that he decided to show them and just rode his own race.

“But the promoters had the last laugh and they stopped giving him contracts for the criteriums – that cost him a lot of money.”

Any article about Schuiten has to mention The Hour Record, those 60 minutes which can launch a career, cement greatness – or break a man.

The cycling press of the day was abuzz with details of the bike, the schedule and Schuiten’s glittering palmares to date. But there’s little doubt that Schuiten and Post underestimated the enormity of clearing a bar which had been calibrated by Eddy Merckx.

And there was none of the special training which Merckx did to simulate riding at altitude. The impression was that taking the record was a formality, Rob elaborates;

“There’s no doubt that his material was top of the bill for the era – the bike, the clothing, it was all perfect.

“But things between my father and Post weren’t the best any more, in 1974 he’d been ‘his boy’ but now he had more stars on the team and my father felt that Post wasn’t so supportive any more, he felt abandoned even?

“And there were commercial interest at play; Post had sold the TV rights to a Dutch broadcaster and to get the satellite link he had to start at THIS time.

“Merckx didn’t have that handicap, his start time wasn’t set for him – the wind is a factor on an outdoor track like in Mexico and you should ride to suit the weather conditions not just for maximum publicity or satellite link.

“People talked as if it was going to be easy but it was a Merckx record; my dad was only 23 years old – a rookie, and if you look at the guys who took the record in that era, mostly it was towards the end of their career.”

Legendary soigneur, Gus Naessens who accompanied Schuiten on the trip to Mexico said that once Schuiten had a Grand Tour or two under his belt and had learned how to really suffer then it would be a different story.

But Schuiten would never again attempt the record.

Many felt that the planning for the bid could have been better, when Merckx rode, he flew in and went for the record within a couple of day before the reduced oxygen content in the air had a negative impact upon his mental and physical state.

Schuiten left it too long and fell victim to the thin air – if the rider doesn’t attack the record quickly, as Merckx did, then he must stay for an extended period to acclimatize as both Ritter and Moser did.

Belgian star Ferdi Bracke attacked Ritter’s record in Mexico several years prior to Merck’s bid, astride a super light bike and with a full entourage in attendance, the ‘chronoman’ from Charleroi left it too long in going for the record and succumbed to the physical and mental torpor which drags an athlete down, failing miserably to dent Ritter’s record.

Schuiten’s move to Lejeune was big news at the time but the Dutchman was never really the same rider again – Rob explains;

“Lejeune were talking to him before The Hour due to the deterioration in his relationship with Post; so were SCiC but my father still had a year of his contract to run so his new team had to buy him out of the contract with Raleigh.

“SCiC wouldn’t pay to buy him out but Lejeune did, they wanted a leader and someone to look after Van Impe in the Tour.

“Henri Anglade was the Lejeune manager but wasn’t as professional as Peter Post; at TI-Raleigh everything was as it should be.

“After Lejeune he went to SCiC, as I said, they wanted him from Raleigh but couldn’t afford to buy him out of the contract.

“He had good years with Saronni at SCiC in a mentor’s role; my father enjoyed the culture, the programme. SCiC was his favourite team, the team strip, the ambiance was good and in Italy it’s the ‘Cycling Life’ – the life you only find in Italy and in Belgium.”

Schuiten won the Baracchi Trophy with Moser and with Knudsen, it’s tempting to ask who was stronger;

“Knudsen; my father rated his first winning ride with Moser one of his best, they started with equal spells but by the end Moser’s relays were short.

“They were second to Maertens and Pollentier in ’76; my father rode with Baronchelli to fourth in ’77 before winning it again with Knudsen in ’78 – he said the Norwegian was a good partner, very strong.”

After his career as a rider finished, Schuiten served briefly as a DS with PDM in 1986 but it wasn’t a success, as Rob relates.

“Steven Rooks and Co. at PDM wanted him out so the team bought him out of his contract and he used the money to buy the restaurant in Portugal.

“He was never really rooted in one place, when he was a boy my grandfather was in the merchant marine and the family spent time in Curacao in the Caribbean.

“Then when he was with Lejeune he was in France then Italy with SCiC so Portugal wasn’t a wrench for him.”

The final question – did he talk to you about any regrets?

“When I was young I didn’t realise how good a rider he was; it’s only when I got into YouTube and Google videos that I realised what a great time trial rider he was.

“When he won the GP Lugano TT in 1975 he was the first Dutch rider to do so; although Zoetemelk won it in 1978. That was a big race with Anquetil, Merckx, Ritter and Ocana all winning it.

“He won the GP des Nations twice, the only Dutch rider ever to win it – and back then it was the unofficial world time trial championship.

“He won the Baracchi twice; Tom Cordes is the only other Dutch guy ever to win – with Rolf Golz in 1990.

“On those results he’s the best time trial rider The Netherlands ever produced – none of the other stars of that era, Zoetemelk, Kuiper, Knetemann won the Nations or Baracchi.

“I think that if things had been different with Raleigh and he’d been able to stay then he would have won a lot more. Anglade at Lejeune wasn’t Post at Raleigh.

“I think The Hour broke him a bit; he felt like a marionette, he wasn’t in control of his fate or given time to acclimatise to the altitude and thin air. For Post it was all about the money; my father had a sponsorship deal with Adidas for his shoes and Post demanded a cut of that because he set up the record attempt. They were talking about his leaving the team even before The Hour and those big fights about money can’t have helped his motivation going for a record set by Merckx.

“I think if he’d been in Mexico for two months and been allowed to prepare properly for it, he’d probably have taken the record.”

Roy Schuiten, ace pursuiter, consummate chronoman and stylist may you rest in peace – you’ll always be one of the very coolest for us at VeloVeritas.