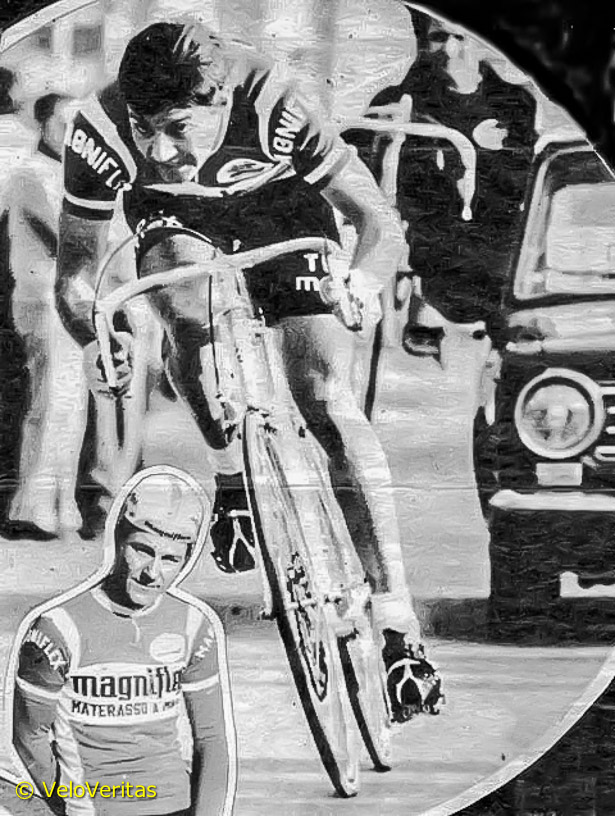

Gary Clively rode two-and-a-bit seasons for Magniflex in the mid 70’s, turning pro on the back of a brilliant fourth spot in the 1975 amateur Worlds road race.

By the end of that season he was grabbing top ten placings in Italian semi-classics like the Coppa Agostoni.

The ’76 season saw a whole raft of good performances; seventh in the Trofeo Laigueglia, second in the GP Camaiore, third in the Giro della Provincia di Reggio Calabria, third in Sassari-Cagliari and a ride in the Giro.

His stand out result in ’77 was seventh in the Vuelta, one place behind Michel Pollentier.

We left Part One of our interview with Garry where he’d just signed with Magniflex,and was getting to grips with life as a professional cyclist…

What were your team mates like with you?

“My team mates from Siapa were very young, like me, and I think they were confused by the arrival of Clyde Sefton and me at first, but once we could communicate better we got along very well and they taught me a lot about surviving in the longer races and stage races there.

“Of course once I had some results on the board they were more accepting of me as an outsider with something to offer the team. When I turned professional I was really made welcome by the guys in Magniflex.

“It must have been novel for them to have a 20 year-old Australian just appear in their ranks from nowhere. I made friends with most of them and they were extremely supportive of me as I tried to adapt to the reality of professional bike racing.

“I had bike problems in the finale of my first race, but a few days later I finished with the leaders in the Coppa Agostoni and it really helped me to be accepted among them as someone with a possible future in cycling. Things tended to change later on, but that had nothing to with anything coming from them and was more a result of changes I was going through apart from cycling. I still remember them as the nicest people, as professional cyclists so often are, and often am reminded of their wise observations on judging the form of rivals, or the kind of intelligence they showed in dosing their efforts throughout the long season.

“I still think some of the wisest and the funniest of people I’ve met were to be found in the world of professional cycling.”

Tell us a Mike Neel story, please.

“In the days following the Giro of 1976 we rode in the GP di Camaiore on the Tuscan Riviera and I finished second, so I was in the good books with my DS. I thought it was a good time to ask him if we could have another English speaking rider in the team and that I knew of someone who would go very well with the Magniflex way of operating.

“To my surprise, after consulting with the owner Franco Magni, he agreed to my request. I got in touch with Mike and he agreed to come to Bologna and to give it a shot as a pro in Italy as soon as he finished with his event program in the US. Mike arrived just a few weeks before the World Championships in Ostuni.

“It was very hot and we were still riding the last long and difficult road races in the Italian lead up to their final team selection for the event. It was a huge initiation for Mike, to suddenly be racing 250 kilometres in 35 degree heat in the hilly courses of Tuscany and Umbria. Nevertheless he finished them all and was also quite a hit in the team and the peloton where an American was something completely new and unexpected.

“Mike was very cool too, so he took it all in his stride and enjoyed the whole experience, never complaining about the difficulty he must have had in adapting to the pro scene going at full gas towards the worlds. There were four of us at Ostuni from Magniflex, in fact Tino Conti took the bronze in the road race, so we had our DS and mechanic & masseur staying at our hotel and looking after us.

“Mike seemed to be already at home with the situation and with only two or three races in his legs set off as a total outsider in the men’s road race. That day was very hot, and every lap we had to do a two K climb up to Ostuni with an undulating stretch of road going on for 10 K before the descent down to the long flat road to the finish. Each lap reduced the peloton, with the hardest part coming after the climb where a hot wind blew across the undulations and really made it impossible to get any rest before the descent.

“It’s well known now that Mike finished in the top ten of that race. He told me after the finish how Frans Verbeeck had grabbed his jersey and pulled on him hard in the sprint for fifth, which may not be such a well known factor in his achievement that day, and just goes to show what an amazing thing he did in not only surviving such a race but in probably being prevented from an even better placing in the end.

“The Magniflex entourage were ecstatic with two guys in the top ten, but you know, Mike was always cool and played it shy.

“But I think even he was more than happy with his ride and it stands out as a key moment in riders from outside of Europe setting the stage for what was to follow in the years of Kelly, Lemond, Anderson, Roche et al.

“Mike was a great team mate and he became very good friends with many riders in the peloton.”

Laigueglia ’76 – seventh; that was a good start to the year.

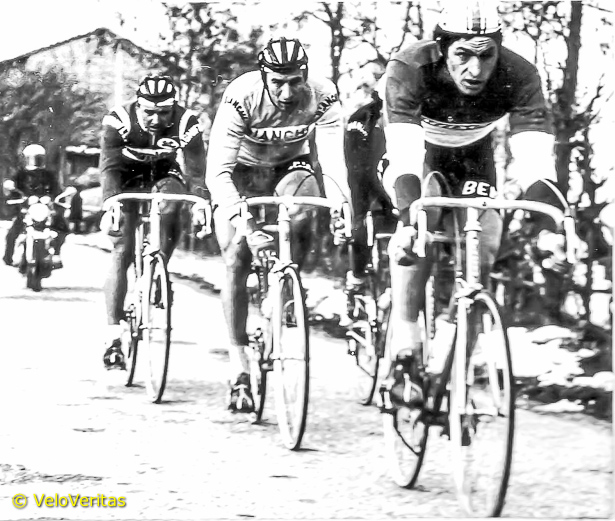

“Yes, thank you, I had attacked on the final climb and been caught by a small group as we began the descent to the finish. There was a fall in the last metres which almost brought everyone down and which saw Roger De Vlaeminck disqualified. A week or so before Laiguelia we had raced in Sassari-Cagliari after the Tour of Sardegna.

“Roger De Vlaeminck was winning everything and that day a group of 10 riders had escaped about 20 K from Cagliari, led by Eddy Merckx & Franco Bitossi.

“I happened to be behind RDV in the peloton and when I saw him drop it into the 13, I did the same and he just moved across the road and wound it up. We rode across the 200m gap to the break in about one kilometre. RDV asked me once for a turn but I was totally gasping and couldn’t do it – it was the most impressive effort I’ve ever witnessed.

“He won again that day, while I managed third. My legs hurt for three days afterwards from the effort I made in following him.

“He was the most incredible rider, always winning and never afraid of anyone, not even Eddy.”

Did you train at home in the winter or remain in Italy?

“Most of the time I did stay in Italy, only once coming home to see my family over the break. In the winters I didn’t ride for at least six weeks.

“I used to run every morning about five K and then walk a lot.

“My DS Franchini was fine with that as I didn’t put on weight and he saw how I would advance quickly once I got back into riding in early January.

“Winters in northern Italy can be very gloomy affairs, with dense fog and a cold stillness which gets oppressive.

“Funny how in those days we sometimes went to the Italian Alps to freshen up in winter, which no doubt had its advantages, but it would have been preferable to head south for a week or two.

“I don’t remember any sunshine between November and February!”

[vsw id=”BI8gKvYLrjo” source=”youtube” width=”700″ height=”450″ autoplay=”no”]

The Vuelta in 1977 and you were 7th, a great ride. Tell us about it, please.

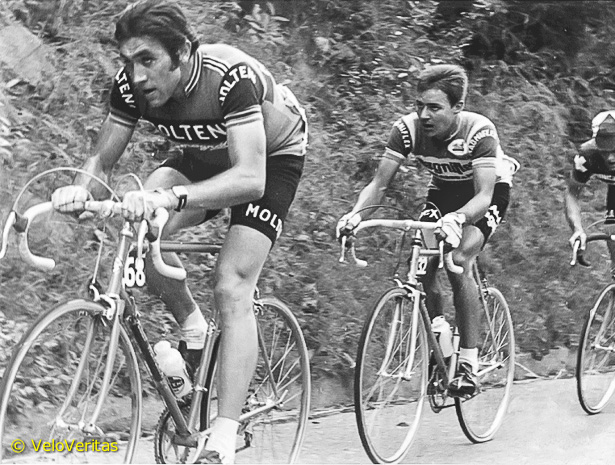

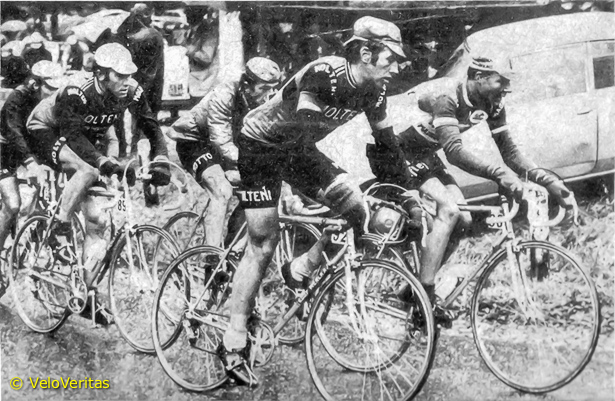

“The story of the 1977 Vuelta is really the story of Freddy Maertens picking off stage after stage (13 in total, ed.) and claiming the overall GC thanks to his consistency and the help of his Flandria team; especially Michel Pollentier in the harder stages.

“You had to be there every day, because Flandria would usually create their own little echelon, with Marc Demeyer and Pollentier reducing the front group to a handful of survivors day after day in the first week or so. On the first or second day it was extremely hot and nobody could follow Fedor den Hertog when he attacked, all of us were glued to the road, but after the damage was done that day, we already knew who would be riding for the GC.

“I came in with Pollentier a couple of others behind a small group with Maertens, so I rode for GC, to see what would happen more than as a serious objective. Each day I got better though and through it all I had one off day in the Pyrenees but didn’t lose much time and then came back the next day so I held my position.

“I was laughing it up with my team mates on the final day when suddenly Flandria attacked, so I missed the break, but still held my spot behind Pollentier in the GC. My DS asked me if I would ride the Giro, starting the next week, but I was still 21 and that really seemed to be going too far too soon.

“He let me off the hook, but then what happened after that, during the summer changed everything for me.”

What was 70’s Spain like – the roads, hotels, organisation?

“Spain was very impressive to me in the 1970’s. We raced there a number of times and I always liked it. Much of it reminded me of Australia. Eucalyptus, red earth, slow dead roads which in the heat made you feel very tired and concentration quite difficult.

“The events were always well organised, we never had any trouble with matters outside of a given race.

“In the 1977 Vuelta, for example, the last day was meant to be a TT in Bilbao, but due to a fatal separatist’s shooting in the town where we finished the penultimate stage in the Basque country, it was decided to run the stage as a road race in a different area around San Sebastian, which the Vuelta management carried off without a hitch and still attracted a large crowd to witness.

“Hotels in those days were much the same everywhere you raced. Usually you had nothing to complain about. What mattered was being able to sleep and that you ate well and on time, which was never a problem, for me anyway.”

Why no ’78 season?

“Well, OK, that’s really a question I can’t easily answer…

“It’s a question that applies to a life outside of cycling and the reasons I did not ride beyond 1977 in Europe had nothing to do with cycling as such. Simply put, I had long been divided by my passion for cycling and my need for an answer to the question of my existence, a typical obsession of my generation, which I had ‘planned’ to address once my time as a cyclist came to a conclusion after 30 or so.

“I’d already had a couple of critical periods to do with this concern of mine during my time in Italy and even before but still maintained my life as a cyclist.

“During the summer of 1977 just as I honestly expected to take a big step forward in my cycling career, things began to change regarding this insistent question of mine and after a further period of subjective upheavals, I finally acknowledged that I couldn’t any longer put off the matter and decided to return to Australia and deal with it.

“At the time, I still thought that I might even return to Europe in time for 1978, but that just was not to be, ever again in fact.”

What did you do between ’78 and your comeback in ’88?

“Nothing out of the ordinary; I got involved, I became a father, I worked and stayed close to home. My interests included learning a musical instrument, painting.

“I read a lot and generally made friends with complete obscurity.”

Your comeback was very successful.

“At the end of 1987 my relationship ended and at the same time I had to move home, which brought me close to old friends from cycling days again and I got interested.

“I was still young enough at 32 to begin training hard and within six weeks of my first training ride I started my first race in more than 10 years.

“That first year was really about relearning how to endure the sustained effort and of course things had changed and the new generation was very strong and aggressive.

“In my second year I started winning again and I suppose the best result then was the national road race championship.

“I had done much better rides even that year, but it meant a lot to do that and put some ghosts to rest.

“The following year I had more good wins and then in 1991 decided that 36 was a good age to stop competing at that level.”

What do you do now?

“For many years I have worked the same job for an importer of large outdoor children’s play equipment. My wife who is from Bosnia and I travel each year, mainly to Europe or Eastern Europe.

“I am a Fourth Way student of the teachings of G. I. Gurdjieff.

“I also study Serbo-Croatian, which helps a lot when travelling in the Balkans.”

What do you think when you look at Aussie cycling, now?

“It’s something of a wonder to me that we can still produce riders capable of the highest achievements at World Tour level while grass roots club cycling has suffered losses in membership and support infrastructure. Probably, the modern style of racing suits our type of road rider slightly more than the older style of last man standing battles, going back a generation or two.

“Still, what the likes of Phil Anderson achieved by racing in the old way, are now being matched by his protégé Simon Gerrans who has a distinctly modern way of gleaning the best results from his cycling attributes. It’s important that we continue to get results in the World Tour, it’s the same for any nation at that level, and I am very happy for those boys who manage to make it worthwhile.

“It’s hard to imagine what a cyclist sometimes has to endure, especially in a period when they struggle on and off the bike and I am very glad they remain a close community who support each other as friends and team mates.

“Many of those who raced in Europe in the 70’s and 80’s are the ones who’ve made enormous efforts to make it possible for young riders to get effective support in trying to establish themselves as professional cyclists now.

“Once upon a time you might go a whole season and not meet another Aussie in the peloton.”

Regrets?

“Perhaps I should have waited another year or two to tackle a three week Tour; completing the Giro at 20 in 1976, took something out of me I still miss 38 years later.

“Nevertheless, I don’t regret anything, because I did what mattered most to me then in racing alongside some of the best riders ever seen, who belonged to the Merckx generation. When such talented and fiercely determined men pit themselves against each other, they used the full palette of human resources to meet the challenge.

“This was a generation who had grown up and developed their attributes out of the ashes of WWII and they were very much loved and respected by their fans for what they gave them.

“I am deeply grateful that I was able to try my hand at learning the art of producing the best in myself as a cyclist from the experience of racing in their company.”

They don’t make them like Garry Clively anymore.