Chief sports writer for The Sunday Times, Irishman David Walsh is best known in cycling circles for being one of the people who have doggedly sought out the reality of Lance Armstrong’s Tour de France victories, not believing the “fairy tale” that defined the American’s recovery from cancer and record series of wins in the world’s toughest race.

The award-winning journalist is the author and co-author of a number of books on the shamed rider’s career and his subsequent fall from grace, the most recent being “Seven Deadly Sins” which Walsh describes as ‘more light-hearted than the others’!

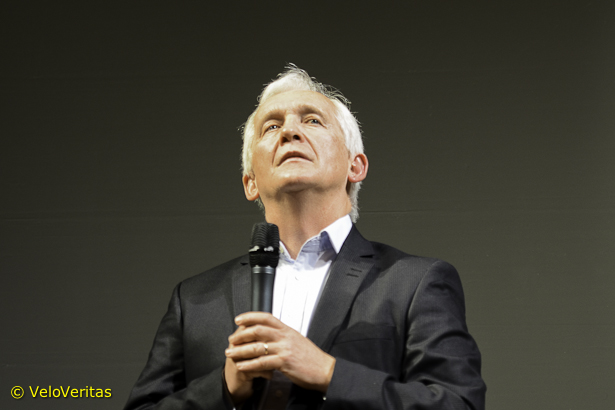

Walsh has been giving talks around the country since cyclings’ governing body’s decision to ratify USADA’s recommendation that Armstrong be stripped of all seven of his Tour victories, and this he week appeared on stage at Edinburgh’s beautiful Lyceum Theatre in the heart of the city to tell a full house of nearly 700 Scottish cycling fans his story.

He’s a good story-teller and it was obvious that the last 14 years have taken their toll on the man, but talking about his involvement with Armstrong from first interviewing him as a young Tour debutant to becoming one of the US Postal Service team leader’s most despised critics, Walsh held the audience enthralled from start to finish and made time for some questions at the end.

We sat down for a chat with Walsh the following morning, before he enjoyed the fresh Edinburgh air with a run around Arthur’s Seat, the huge, beautiful park – complete with extinct volcano – in the city centre, and in part one of the interview we discuss Armstrong and his motivation for behaving the way he does, and what can be done about the lack of faith the cycling community has in the UCI leadership.

* * *

On Lance

The second part of Greg LeMond’s quote has turned out to be the accurate one; “…the greatest fraud in the history of sport”. But what now? The sport seems to have weathered the storm, Lance is not the same hot property he was, and cycling continues on…

“Ideally, the thing that most needs to happen now is that the leadership of the UCI needs to change. And I would say that if Pat McQuaid was sitting here saying ‘I’ve done nothing wrong, I’ve been anti-doping since I’ve been President and we’ve made great progress so why should I resign?’. I would say Pat, you’ve got to resign because you were there in a position of power, whether it was on the Management Committee, or incoming President, or the President when Lance came back and the UCI facilitated his comeback by bending its own rules, you were there through this horrific period and as long as you remain the sport is going to lack the credibility it deserves.

“If Pat McQuaid could see what cycling would look like without him, if he stepped away from it and Verbruggen stepped away from it, people would immediately say ‘OK, let’s see this new guy, let’s give him a chance’. A lot of people are not going to give these two guys a chance again because they feel so betrayed by the leadership of that era.

“Also, people have got to talk openly about anti-doping and say ‘yes, we understand how expensive the testing is, but we can’t have the sport without rigorous testing – the feeling will always be that when budgets need to be tightened, anti-doping will be adversely affected – and has been, and that’s going to keep happening. The UCI are basically motivated to make a profit to be able to keep their staff in jobs, in the lifestyle they’re accustomed to. I’m sure when the UCI officials – sports administrators in general, not just in cycling – fly they don’t fly economy, and business class 1st class travel is hugely expensive; and that all has to be paid for but I’d rather that money went on anti-doping.

“Imagine if a leader of the UCI came in and said ‘I will never travel Business Class, and no member of our staff will because that’s money we could be spending on anti-doping, everybody would say ‘brilliant! Here’s people who think about the sport and love it like I do, who are prepared to make the sacrifices I would make if I was in a position of power.’

“It would be a symbolic statement for Pat McQuaid to make – I’ve done a number of talks now, and in these venues where I’ve said cycling cannot have credibility in terms of its governance until Pat McQuaid and Hein Verbruggen leave, there’s been a spontaneous round of applause, so cycling fans (certainly in Britain and Ireland where I’ve spoken) are all adamant that there’s something wrong and it needs to move on.”

Isn’t it odd to have a President of a sports governing body (and this doesn’t just apply to cycling) who should really just be the mouthpiece or maybe the chair of the management committee and who seems to have an extraordinary amount of power within the organisation?

“Certainly it comes closer to a dictatorship than a democracy.

“You have the sense that Pat McQuaid has the right to act in an autonomous way – he should only be representative of the organisation’s or the committee’s views, not just of himself.”

One of the quotes I remember from your book ‘From Lance to Landis’ was Emma O’Reilly saying to Lance ‘you’re a paranoid freak’ (Lance had set a ‘trap’ in his hotel room in case an angry local tried to get to him), and it makes me wonder whether Armstrong’s behaviour and attitude was a choice, or was he programmed that way?

“I asked a forensic psychiatrist ‘what’s the difference between a sociopath and a psychopath?’ and he said ‘there is none. People think sociopath is a milder form of the condition, but in technical terms there is no difference’.

“There’s a psychopathic scale of measurement in this field that goes from something like five to 32, with 32 being ‘serial killer’ and five being the most benign; honest decent people who would feel compassion for everybody, where a serial killer feels compassion for no one We all sit somewhere on that scale.

“People say to me ‘if you were ever to interview Lance and had just one question to ask him, what would it be?’, and whilst there isn’t really one specific question there is one area that I’d like to explore, I’d want to discover why he is the way he is – nature and nurture.

“Was he just born with a natural predisposition to want to succeed at all costs or was this something that was brought on through a difficult childhood? Abandoned by his biological dad would definitely make a difference to someone, make them harder; I’d ask him ‘what was it that made you put your hand on a bible in the SCA tribunal and speaking under oath about Emma O’Reilly say the things you did… what is in you that makes your behaviour different from people we would call normal?’ Because normal people don’t behave like he does…

“Oprah asked this question and his answer was to say that ‘when I am attacked my response is to attack back’.

“Okay, we know what you did Lance – I want to know why you did it.”

Most people would, for example, realise the importance of putting their hand on a bible and swearing a testimony in front of lawyers and a video camera. It’s pretty obvious to anyone that his body language in the SCA video testimonies indicates he’s lying.

“Yes, all the signs are there.

“Apparently a psychiatrist has looked at the video of the Opera Winfrey interview and he says that the tell-tale signs of being a psychopath are all there.

“It was really difficult for Lance in that Oprah interview and I felt a certain amount of sympathy for him, on the basis that he knew that he had to look and seem remorseful but in the end he couldn’t carry it off, emotionally or intellectually.

“He couldn’t see the significance of talking about the period the sponsors left him and he had his ‘$75 million’ day, expecting people to feel sorry for him, but we were actually all looking at him thinking ‘but that money wasn’t rightfully yours in the first place’ but he can’t see it like that, he thought it was his money and now somehow it was being unjustly taken away from him.

“Imagine if he had said ‘I lost all that money and I actually felt good about it because I’d always felt that I got it under false pretenses’…”

That sounds like the kind of thing that Tyler Hamilton might have said…

“Yes! ‘I’m glad it’s gone and now I can start again, from a better place’.

“Lance is only sorry he got caught, not for what he did.

“Lance thought that his life was like a set of weighing scales; on one side he was putting the bad and on the other the good, and he thought there was a balance there. He was addressing the bad by his work in the cancer community, but life doesn’t work like that; Al Capone was a great cancer donator in Chicago but he still went out and murdered people. Doing some good doesn’t necessarily mitigate all the bad.

“He says he was ‘caught in a trap’, he was created into an iconic figure and he ended up having to act the role… well, actually, he did a lot too to build that image.”

I imagine Lance and his entourage realised the power of the fairy tale early on and did what they could to maximise the earnings from it?

“Well there is the quote that I used in “Lance to Landis” that Bill Stapleton gave to journalist Mike Hall way back in 2001, where Stapleton talked about this ‘brash Texan’, from a single parent family, who wins the Tour de France… it’s a big deal, but not that much of a story.

“‘But then’ he said, ‘you layer on “Cancer Survivor” and that creates a different brand – much bigger’. In terms of the creation of the icon, the cancer aspect was the key factor; winning the Tour was big, but winning the Tour as ‘the guy who beat cancer’ lifted it to another level.

“Lance said himself that he ‘beat cancer’, which I always though was wrong – you survive cancer, you don’t beat it. Did that mean that Lance felt that other people ‘lost’ to it?

“Lance was unique in so many ways… cycling was at a crossroads in 1999 [following the Festina scandal at the Tour de France a year earlier] and we all believed that things were surely going to head off in a better direction. The French started their longitudinal testing system then, monitoring people regularly, and Jonathan Vaughters wrote that when he went to Crédit Agricole he was staggered by how little medications they used (not just relative to USPS but by any comparison), they didn’t even use much in the way of legal products.

“USPS used to travel with a virtual pharmacy! I heard talk about the riders ‘filling their bags’; they had a white bag for legal products and a black bag for doping products. Two bags, but they needed both.

“When Jonathan went to Crédit Agricole he found that the team had transitioned to a much less ‘medial supplements culture’ – and that’s the way the sport could have gone, but Lance was hugely influential in ensuring the sport didn’t go that way because if he won the Tour de France by doping, well then he set the bar at that level meaning that the others would have to dope too, in order to reach it.”

Do you think Armstrong realised after the Festina scandal in ’98 that the French (if not other nations or teams) had backed off from the organised and institutionalised doping regimens, and thought that if USPS ramped things up a gear they could distance a good proportion of the Tour peloton before the race even began?

“Absolutely. He would have known exactly what the French were doing, and he also likely realised that the Spanish were not going to change and some of the Italians weren’t going to change, the Dutch may or may not change (and we know now many didn’t)…

“What was really offensive about that era was that the French were complaining that the sport still had a problem, was operating ‘a deux vitesse’, and very few people said ‘you know what, they might have a point here, they might indeed be clean and the rest doping’. The French haven’t produced a winner of the Tour de France since Hinault in 1985, twenty-eight years ago.

“That’s completely illogical, and simply would not be the case unless doping had had such a profound effect on the sport. France was the number one country in the world for cycling in terms of its roads, its mountains and its climate, its love of the sport, the amount of racing that goes on in the place – the bottom of the pyramid is really wide, the French authorities are much more serious than those in other countries, the French teams got the message and bought into the idea of a cleaner sport, they were the first country to make doping a criminal offense… so it’s reasonable to believe that France would have produced a big star in the sport every so often, but if that person is clean he’s at such a disadvantage that’s he’s never going to become the great champion he should.

“People need to face up to that bloody reality; they might laugh at the French and say they’re lazy or whatever, but that’s unintelligent nonsense and I saw some really serious journalists making that argument and I just thought it was disgraceful.”

What could – or should – Lance do now to try to help the sport he says he loves?

“I think there’s one main thing that he could do: go to WADA, be the first guy through the door at a Truth & Reconciliation Hearing (or whatever the mechanism turns out to be). Say ‘I want to do a full interview and I want to tell you everything’.

“Actually though, I don’t think he can do that now.

“People think he wants to hold onto as much of his fortune as he can, but that’s not the biggest challenge facing him.

“What he’s contending with now is keeping himself out of prison, because when you perjure yourself as much as he did, when you go into witness intimidation as he did – and in multiple countries, you don’t know where something’s going to come back and bite you.”

It’s strange that with all this hanging over him Lance is still trying to enter swimming competitions and appears to be able to brush it off, he seems to operate almost unaffected.

“Yes, he needs to compete.

“I don’t think he really has a feeling that he has hurt or wronged anyone, he has the sense that he is the victim.”

Paul Kimmage has a better relationship with Floyd Landis these days after sitting down with him, hearing and working through his story directly. Do you think there will ever be a time when you and Armstrong turn the corner in your relationship?

“Eh… no.

“Because I’m not sure he has the capacity to really see what he did in the way that I believe he has to see it.

“He has to understand that he behaved in the most disgraceful way. Even if he has done a lot of good things, it doesn’t mitigate that. That’s where Oprah was brilliant in her interview; she didn’t allow him to explore that.”

Thinking about the actual mechanics of what went on, the blood bags hanging from picture hooks in hotel rooms or taped onto the wall of the bus, it’s truly horrid.

“It is, it’s horrendous.

“Hollywood is now very interested in the story, and apparently there are a number of films being planned. The first film that shows – and makes it clear that this is a true story – that USPS team bus on the small Alpine road, with Johan Bruyneel telling the driver to pull in the next chance he sees, get out and pretend that there’s something wrong with the engine, and the riders all lying down and getting their blood bags transfused into them… it’s going to be staggering.

“The greater public think that doping is done by taking a little clean pill and you only get blood transfusions in a hospital, they don’t imagine it happened on a team bus in the late afternoon at the Tour de France with fans milling around and camper vans driving past, they will see this and are going to be astonished, that this appalling deception at the biggest bike race on the planet was being acted out in their midst.”

We know now that USPS wasn’t unique amongst the teams in their methods used during that period, but what was it about their approach that set them apart from the others, like Rabobank for example?

“They had a lot of money to use on the program, which was key, but I also think that Michele Ferrari was very bright and clever in the way he did things.

“If you eliminate the question of morality and ethics and just focus on the need for results, you would say that Lance was brilliant in terms of how he organised the team, the way they trained, the nutrition… Lance was excellent at all that stuff.

“You had guys in that team who said ‘I don’t want a full-on programme, I’d rather follow a ‘doping-light’ programme. I don’t want all that stuff in my body but I do want an advantage’, but Lance would have been the one saying ‘no, you work with Michele’.”

It was a necessary component of the Tour squad preparation as well as the pervading culture in the team…

“Yes, it was; In Christian Vande Velde’s USADA sworn affidavit he describes a scene where he’d ridden the Tour in 2001 and crashed, not finishing the stage; he was out of the Tour.

“That evening the team doctor Luis Del Moral gave him an ampule of cortisone telling him to inject half now and half later – not even for performance gains; he was leaving the race next morning for home, but it was just to help with his recovery.

“So Christian drew half the ampule’s contents into his syringe and took it, and placed the ampule down on the table.

“Bruyneel was in the room and came over.

“He picked up the ampule and pulled the remainder of the contents into a clean syringe and injected it into himself, there and then! Just to make himself feel better, just for a sense of well-being!”

* * *

On the UCI

Paul Kimmage talks about a “root and branch” clearout being the only way to turn the page in the sport of cycling, but as you said earlier it needs to start at the top. What about blocking Pat McQuaid’s nomination for a third term as President of the UCI by having the cycling clubs in Ireland call for an EGM and vote against backing McQuaid? Would you take part in such a move?

“Yes, I’d have no problem in being involved in such a lobby.

“I’d love to see a grassroots movement against Pat McQuaid, but it would need to be very concerted because the people involved at the top of Cycling Ireland, and indeed sports federations everywhere, well they’re not easily moved – even when it’s clear the majority want movement. They’re resistant to change and they’re people who are prepared to brazen it out.

“Anthony Moran [former Vice President of Cycling Ireland and the one man who voted against backing McQuaid at the recent CI Board Meeting] makes the point that going into the meeting he thought it was going to be 4-1 or 3-2 against McQuaid, but when it came to the vote it was 4-1 in favour of McQuaid, and he was staggered, so that’s how difficult it is. It’s how dictatorships work; each person pursues his own agenda, and keeps himself beyond scrutiny.”

When the UCI came up with the 50% Hct limit, it effectively gave the green light to those riders prepared to dope to a certain level using substances like EPO for which there was no test at the time. What more, or what else, could the UCI have done once they knew there was a big problem in the sport?

“The rule itself wasn’t so bad I guess, but it did legitimise doping up to a very high level, given that the riders knew how to get their Hct levels down using saline solutions and whatnot.

“If the UCI had really wanted to eradicate doping at that time, what they would have done is say ‘we know there’s an EPO test nearly ready, in the next 18 months, and we suspect many of the current top riders are doping using EPO. We whole-heartedly disapprove of this so we’re not going to announce anything, we’re going to – very quietly – speak to the French lab and tell them to hang onto all of the samples from the testing and when the test is ready we’re going to retest all the samples, and then if necessary we’re going to ban the lot of them.

“What a message that would have sent out! Lance would have lost his first two Tours, along with all the other victories he got in that time, and he would have got a four year ban. The message would have been really powerful because it would have been a lot of riders sanctioned, virtually everyone they tested, but so what? The message would have been ‘don’t presume what you’re doing won’t come back to bite you’.

“The UCI didn’t want to take that stance because the commercial potential of Lance winning the Tour was huge, and you could argue that cycling has become more famous because of Lance Armstrong…”

I’d rather have my ‘not quite so famous sport’ back please!

“Absolutely! A bit more purity for a bit less popularity would be a fair trade.”

Riders with a doping sanction on their records cannot now go into team management, but the sport is still full of guys who – perhaps – don’t know any other way to achieve success. Some, though, are widely regarded as doing a good job (like Jonathan Vaughters) and some clearly feel they are unable to tell the truth about what happened when they were racing. What should be done about those people?

“I think we maybe just have to wait until it gets to the end of their natural lifespan in the sport.

“There are two types of former doper: the guy who denies everything, says he doesn’t know what you’re talking about; guys who just lie about their past doping. I’m very uncomfortable about having guys like them in the sport.

“Then you have a guy like David Millar come along and tell the truth and want to discourage others from doping. I’m much more supportive of that type of person.

“My feeling is that too many continental Europeans who have doped almost have a vested interest in the sport going back to how it was before, in order to legitimise their own careers. It’s not a coincidence that it was Eddy Merckx who introduced Lance Armstrong to Michele Ferrari…

“I’ve said this many times; Bernard Hinault felt he was utterly entitled to ‘correct hormonal imbalances’, to wake up the morning after a hard stage and replace the hormones and testosterone he ‘lost’ the day before.

“But what you had with Anquetil, with Merckx and with Hinault was guys who had the capacity to win the Tour de France clean, and importantly when they first rode it at 21, 22, 23 years of age, whereas in the Armstrong era we saw that EPO and blood transfusions gave riders an entirely new capacity, it changed riders.”

Check out Part 2 of the interview where Walsh discusses more doping topics, being embedded with Team Sky, Change Cycling Now and what’s coming next for him.