The story that the East European propaganda machine circulated after the 1952 Peace Race was that the “Westerner” winner Ian Steel had been approached by his country’s intelligence agency before he travelled to the race and was asked to; ‘keep his eyes open’ whilst behind the Iron Curtain – to spy, in other words.

The rider declined and received a telegram from his employer on the day he won, firing him from his job.

All nonsense, of course.

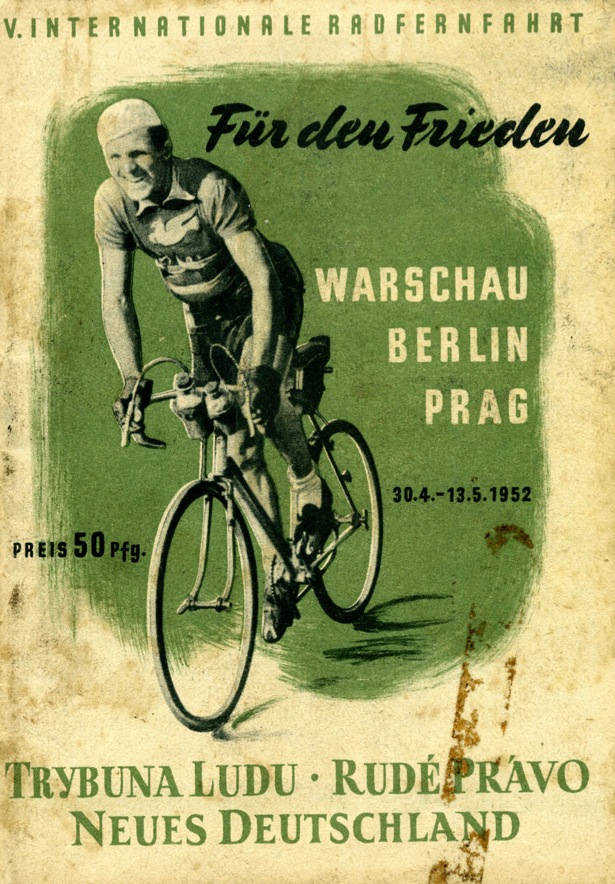

But the Peace Race wasn’t just a bike race; it was where the East could battle with the West in the Cold War – and demonstrate their physical and mental superiority over the decadent Capitalists.

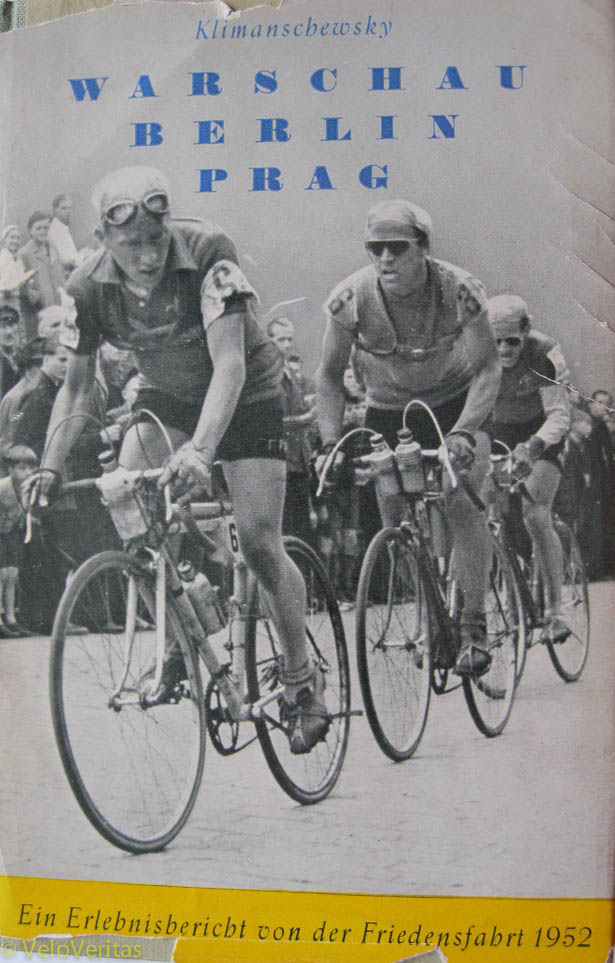

‘The Peace Race,’ Warsaw to Berlin to Prague.

When I was a boy it was spoken of in hushed tones.

The East European riders were the hardest of the hard – as they had no problems demonstrating when they came to the UK to ride the Milk Race and its little brother, the Scottish Milk Race.

They dominated the amateur world championships – road and team time trial; and won every notable amateur stage race world-wide.

During the entire history of the Peace Race from 1948 to 1989 there were few Western winners and no English speaker ever won.

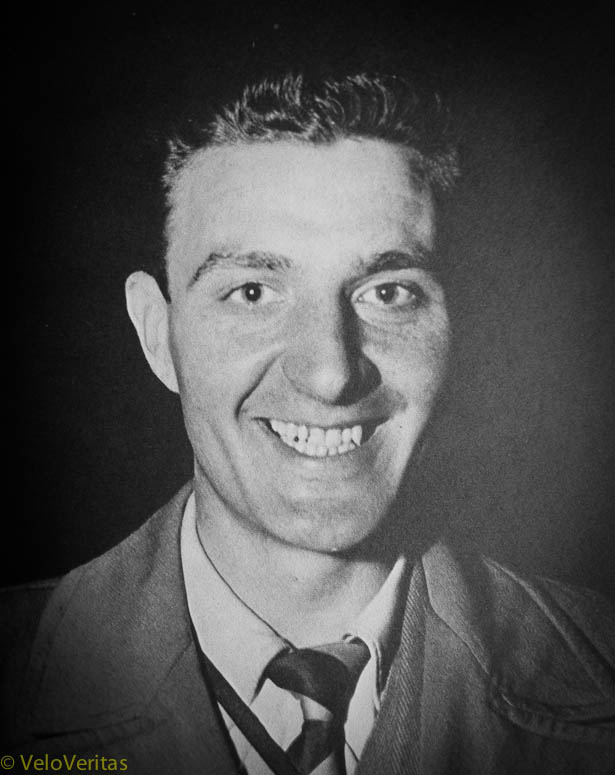

Except one that is, in 1952, the year we mentioned in our opening paragraph – the rider was Ian Steel of Scotland.

As Steel himself says;

“We were very unpopular winners, there was supposed to be a Tatra car for the winner and motorbikes for the winning team – but they never materialised.”

And as VeloVeritas pal and Peace Race aficionado, Ivan explains; “Traditionally the leader of the race would wear a yellow jersey which bore Picasso’s representation of the white dove of peace.

“But not Steel, he wore a plain yellow one while Stablinski, an earlier leader of the race was given one with the dove; the same was true of the blue jerseys of the leading team, no dove on the blue jerseys given to the GB team while earlier leaders, the GDR, were given blue jerseys with the white dove.

“And there were no laps of honour for Steel and the GB team in Prague.”

Steel takes up the story;

“There had been Danish winners in the past but they weren’t seen as being as close to the Americans as the British; and Britain was a member of Nato, unlike Denmark.”

Despite the lack of enthusiasm for their performance the team was well looked after;

“We had a great interpreter with us all the time and at the end of every stage there was a boy or girl scout there for you to take your bike and give you a blanket to wrap yourself in – and hot mug of tea.”

The win may have been an unpopular one with the East Europeans but the British Government didn’t want the team to go in the first place;

“‘If you go over there on a British passport then we wash our hands of you’ they told us,”

says Steel. He recalls that it was an alternative British group which met the team in Poland, not official embassy staff.

Ivan explains; “there was GB consular representation in all three Peace Race cities but they would not be interested in looking after some cyclists.”

And Steel’s BLRC (British League of Racing Cyclists) team was the ‘second choice’ GB squad for the race – the original invite went to the BLRC’s bitter rivals, the NCU (National Cyclists Union) who refused it.

The welcoming of the teams fell to Marshall Konstantin Rokossovsky, Marshall of Poland and Polish Defence Minister.

Steel remembers;

“He was very animated – but that was probably the vodka!

“All of the teams had a greetings message prepared for the Marshall, but of course, we didn’t.

“Bev Wood suggested ‘bollocks!’, so when it came round to our turn to meet the Marshall, we chanted in unison; ‘Bollocks!'”

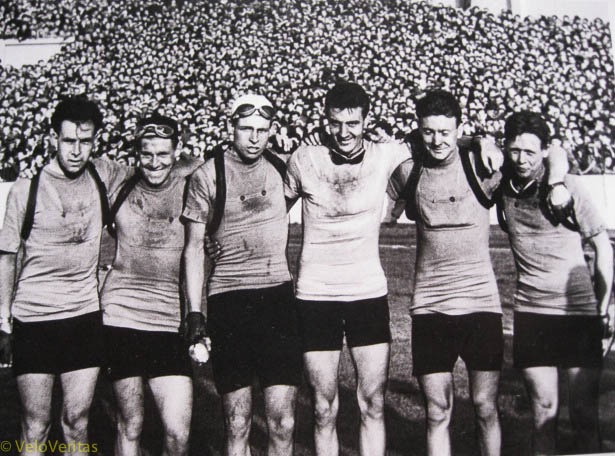

Steel also recalls that the squad had no team uniforms;

“Les Scales was the only one with a blazer so he was chosen to lay the wreath at the Soviet monument.”

The roads were every bit as bad as legend suggests;

“We had to wear goggles to protect our eyes from the coal dust.”

He also remembers that the Belgians had many mechanical problems;

“They were constantly breaking frames. The Italians were on lovely bikes, I remember that their spokes gleamed – ours were dull.

“They offered the Belgians their spare bikes, which had Campagnolo Paris-Roubaix gears; I had to teach the Belgian riders how to use them!

There was a French/Polish team too – for second generation Poles living in France.

“They were good but didn’t ride in a coordinated manner; they had Jean Stablinski on the team who went on to be world professional road race champion.”

The GB team made friends in the right places, as Steel says;

“The German TV reporters took to us and before the Berlin stage they said to us,’the GDR (East German) team is going for it today.’

“We were in the second echelon and held them, but it was a very hard stage with the cross wind and the pavé.”

The mountains of Czechoslovakia suited the GB team better. Steel took the jersey on stage eight and defended it until the bitter end.

Steel recalls that team manager Percy Stallard had the situation under control;

“He could fall out with anyone but we could get round him and he was very good tactically.

“We all had four danger riders numbers marked on our stems and those were the ones we had to keep an eye on.

“Whilst Frank Seal’s job was to stay with me all the time, he had the same size of bike as me.

“Our tactics on the last stage were simple; Percy Stallard said; ‘whatever happens, don’t let Vesely get away!'”

Vesely was a national hero in Czechoslovakia, winning the Peace Race overall in 1949 and 16 stages over the years he rode it – as well as the Tour of Slovakia in 1955.

“At the finish in Prague, Vesely congratulated me.”

recalls Steel.

In the book on Vesely by Josef Pondelik, ‘A Life in the Peloton’ the Czech rider said that he; ‘admired the GB team’s solid teamwork, cool under pressure and their stone confidence.’

There was very little fuss made over the individual and team victory in the UK, Steel remembers;

“It was no big deal, there was a 12 word Reuters report; the left-wing ‘Daily Worker’ (now The Morning Star) covered it and there was a photo in the ‘Picture Post’ magazine.”

But East/West divide or no, the Peace Race remembers its own and in 1968 he was invited to the 20th anniversary race, Steel remembers;

“Gustave Schur started the race, he released the doves of peace. I sat in a press car for the first stage, the reporters were all asleep, they’d been boozing!

“Tave Schur was a real character, he won the race in 1955 and 59.

“The year I won he was awarded a piglet as a prize on one stage; he let it loose at one of the official dinners – chaos!”

On the 50th anniversary of Steel’s win one of his friends contacted the Largs & Millport Wee Paper who interviewed him.

Then Glasgow Evening Times picked up on the story – ‘Forgotten Hero’ was the headline.

VeloVeritas can but agree with those sentiments.

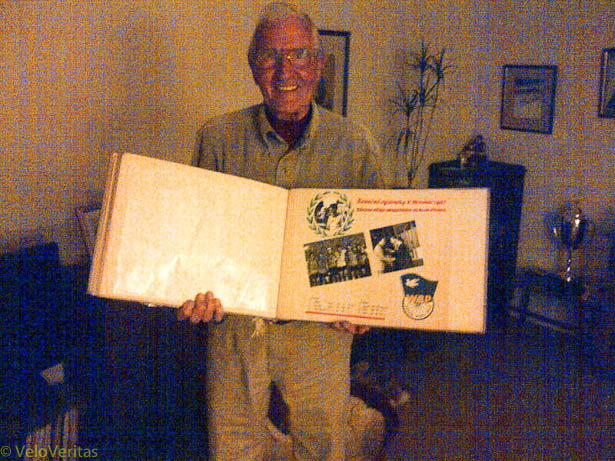

We’d like to acknowledge the help given to us by our friend Ivan, whose knowledge and enthusiasm were essential in our preparation of this piece.